Through decades of intensive search activity, astronomers found four mini-planets orbiting the closest solitary star system to Earth. The astronomical discovery represents a groundbreaking scientific step, establishing new avenues for exploring planet development and off-Earth life examination.

Through the Barnard’s Star discovery, scientists uncovered four planetary bodies.

Scientists from the astronomical community explore Barnard’s Star because it exists six light-years from our planet as a red dwarf. The Gemini North telescope located in Hawaii allows researchers to confirm the existence of four sub-Earth exoplanets using the high-precision MAROON-X instrument. Four exoplanets discovered by scientists rank as some of the tiniest planets detected by researchers at 19% to 34% the size of our home planet Earth.

Astronomers found these planets after employing the radial velocity technique that measures star wobble caused by the orbiting planet’s gravitational force. The new discovery method permits astronomers to locate exoplanets beyond the transit detection capability because it enables researchers to detect minuscule distant planets. The world has taken a significant leap toward discovering Earth-like planets beyond our solar system.

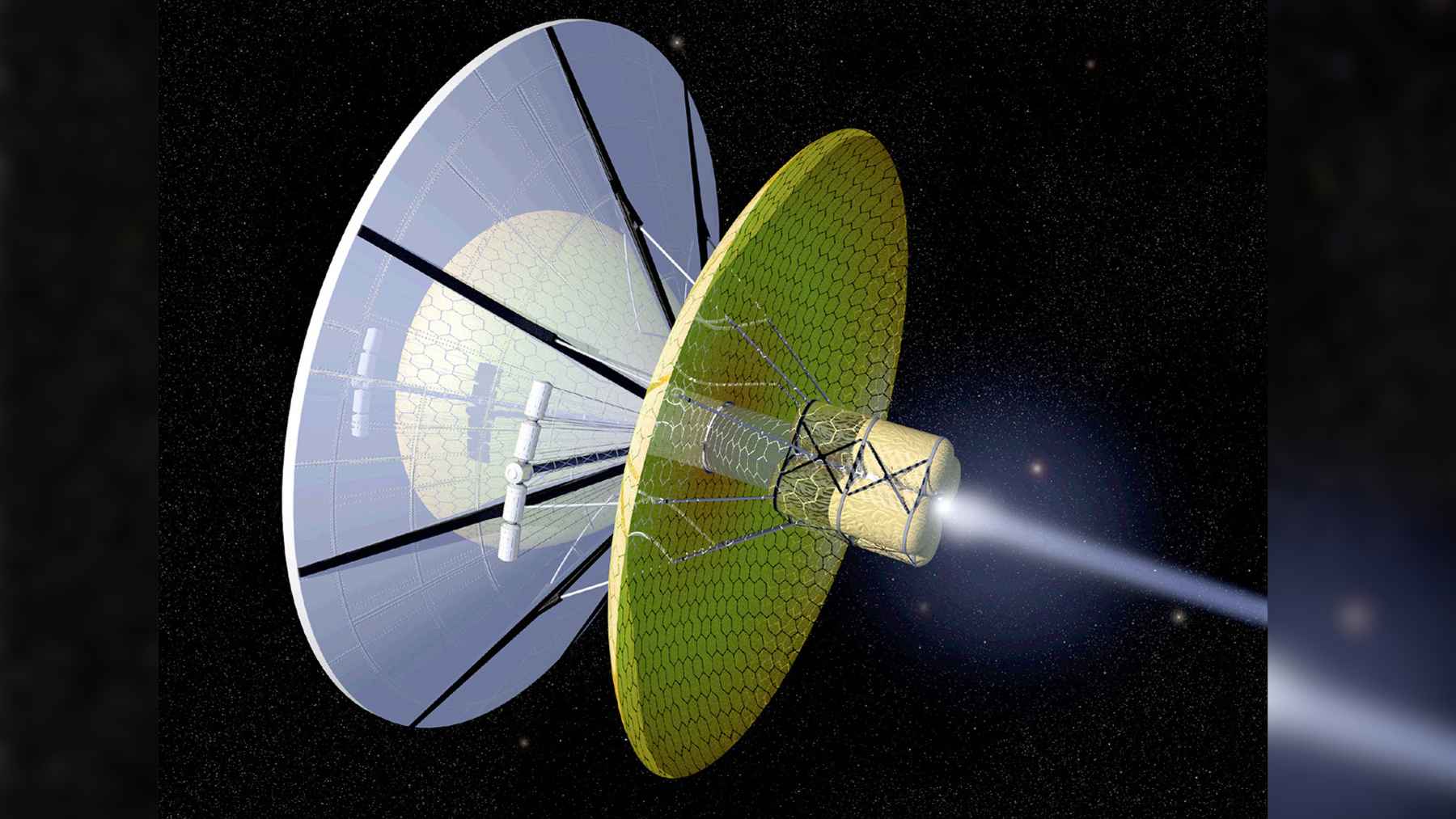

With MAROON-X, scientists have demonstrated its powerful capabilities, which transformed exoplanet detection methods forever.

Jacob Bean and a University of Chicago team constructed the instrumental technology known as MAROON-X, which served as the essential instrument for this breakthrough. The Gemini North telescope holds MAROON-X, which serves as a tool for identifying distant exoplanets surrounding red dwarf stars at high accuracy levels. The measurements of wavelength changes in starlight enable MAROON-X to detect and calculate how many planets, together with their masse,s affect the star.

Measuring exoplanets around Barnard’s Star required the MAROON-X instrument to operate for 112 consecutive nights for three years for scientists to prove the existence of three planets orbiting the star. Analysis using the ESPRESSO instrument on the Very Large Telescope in Chile showed that a fourth planet exists. According to this recent discovery, advanced spectrographs have demonstrated better capabilities to detect smaller exoplanets.

Could these planets support life? Here’s why scientists say no

The four newly discovered planets belong to the category of rocky worlds, which share a composition similar to Mars. The four planets orbit Barnard’s Star from a short distance and circle the star in under seven days. The closest planet’s orbital cycle takes less than three days, yet the outermost planet orbits its star in about seven days.

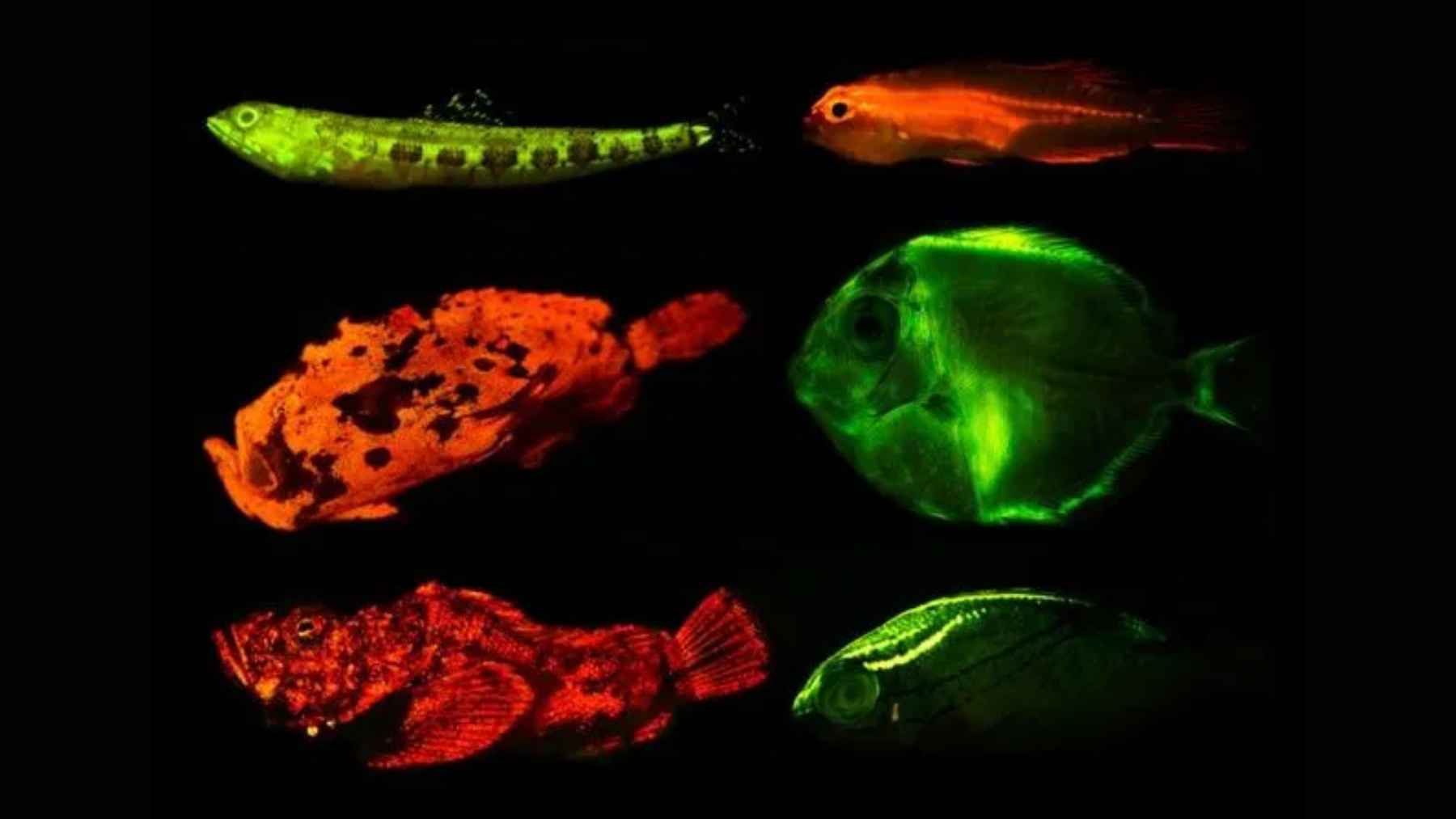

The close distance to Barnard’s Star makes these planets uninhabitable due to excessive heat. The planets exist in a hostile environment because stellar flares and intense star radiation destroy any existing atmosphere, which denies them life support. These planetary findings lead scientists to grasp more about the development process of minor rocky exoplanets.

What’s next? The discoveries will alter future space exploration operations

Exploring these four planets orbiting near local stars represents a major progress toward finding planets of Earth-like size. Next-generation spectrographs ESPRESSO and MAROON-X have proven their ability to confirm the discovery of small planets at increased accuracy. The discovery breakthrough allows scientists to analyze different exoplanets and investigate conditions suitable for supporting life beyond Earth.

Scientists believe that smaller exoplanets contain diverse chemical compositions compared to larger exoplanets that scientists have discovered yet. Researchers will acquire better knowledge about planet formation by locating more tiny celestial bodies while determining which worlds possess life-supporting capabilities. The success of MAROON-X enabled it to obtain a permanent position on the Gemini North telescope as the device continued developing innovative exoplanet discoveries.

Astronomers made an exceptional scientific advancement following the discovery of four exoplanets orbiting Barnard’s Star that exist smaller than our planet. ESPRESSO and MAROON-X serve as intelligent instruments to expand human knowledge about outer space. According to recent astronomical findings, searching for new space discoveries holds endless potential beyond our solar system.