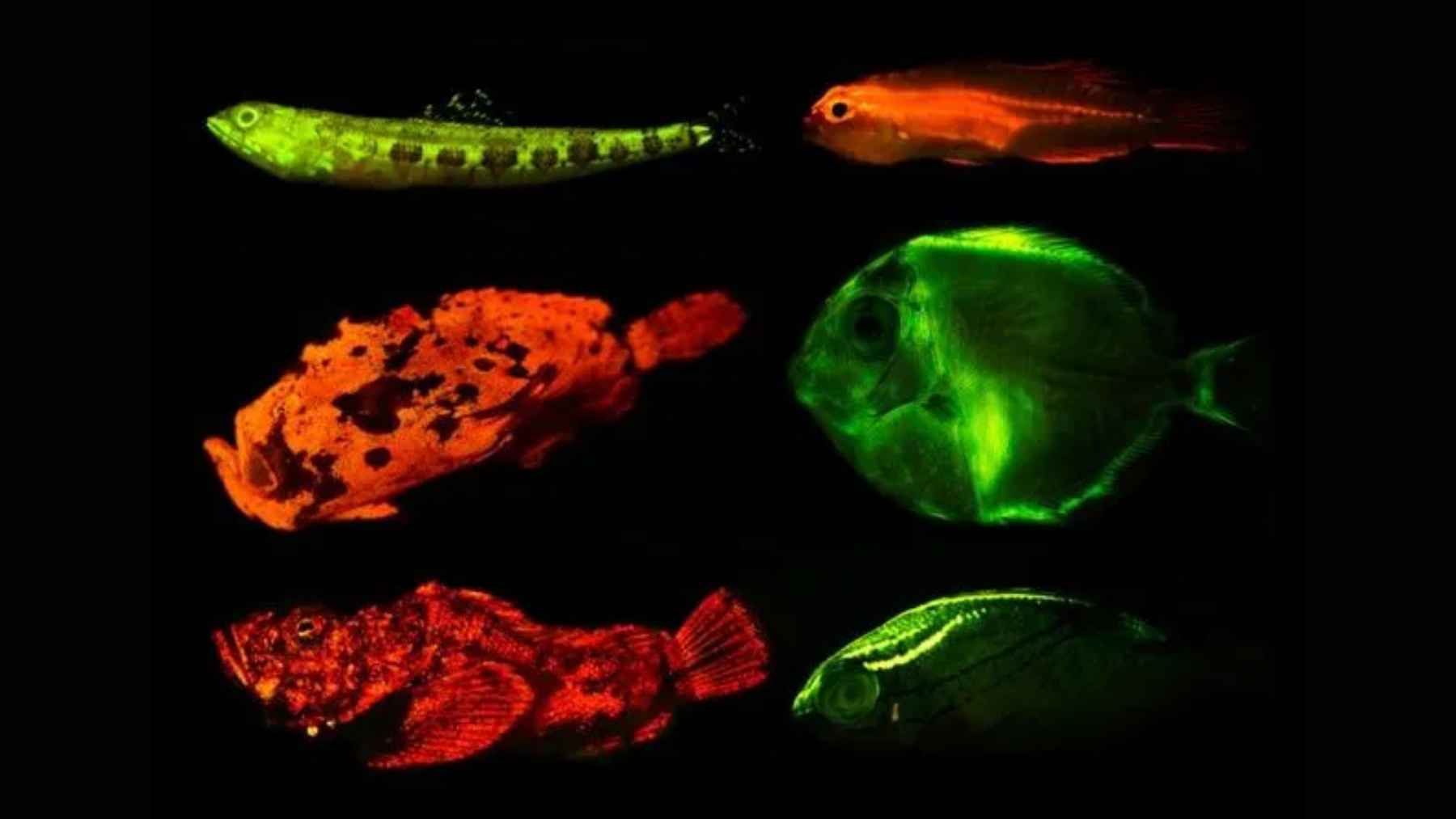

Fish have been glowing in the dark seas longer than humans have walked on land. Two new studies led by the American Museum of Natural History show that biofluorescence in marine fishes dates back at least 112 million years and has evolved independently more than one hundred times since, first emerging in eel-like ancestors.

The work, published in Nature Communications and PLOS One, also reveals that most glowing lineages are tied to coral reefs and that their colors are far more varied than scientists realized.

What biofluorescence is and how it works underwater

So what exactly is this glow, and why did it last so long? Biofluorescence happens when an animal absorbs high-energy light, usually blue, and re-emits it at longer wavelengths that appear as green, orange, or red.

In the new analysis, researchers pulled together every known case of biofluorescent bony fish and added measurements from museum expeditions.

They documented 459 fluorescent teleost species, including 48 that had never before been recognized as glowing. Using a time-calibrated family tree, they traced the earliest origin of this trait to true eels in the mid-Cretaceous, more than one hundred million years ago.

Coral reef fish evolve fluorescence faster than non-reef species

The same models show that biofluorescence is especially common in coral reef fishes that live in shallow tropical waters. Reef associated species appear to evolve fluorescence at a rate around ten times faster than species that live away from reefs and they also gain and lose the trait more often over evolutionary time.

That burst in fluorescent lineages lines up with the recovery of modern coral reefs after the Cretaceous Paleogene extinction, when reef-building corals and their fish communities expanded again. Reefs emerge as places packed with color and shadow, where turning blue light into other hues gives fishes extra contrast for hiding, finding mates, or spotting prey.

Coral reefs under climate pressure and what it could mean for glowing fish

That link matters because reefs are under pressure today. Warm water reefs hold about a quarter of marine biodiversity yet are among the ecosystems most at risk from ocean warming and acidification.

Scientific assessments warn of global reef declines even under relatively low warming levels. Recent years have brought an unprecedented global bleaching event, with more than 80% of monitored reef areas exposed to extreme ocean heat between 2023 and 2025.

If the living stages for fluorescent fishes crumble, many of the intricate light-based behaviors these studies hint at could vanish before we fully understand them.

A wider range of fluorescent colors than expected

Beyond timing, the team also asked how many kinds of glow exist. With specialized cameras that shine ultraviolet and blue light and filter out reflections, they measured the emitted wavelengths of dozens of species collected over the last fifteen years.

Some families showed at least six distinct fluorescence peaks, so a single group of fishes can produce multiple shades across the green to red part of the spectrum. In some lineages individuals combine red and green emission on the same body or show different colors between males and females.

Why fish fluorescence matters for science and conservation

At first glance these results might sound like a curiosity that only scuba enthusiasts would care about. In reality, biofluorescence is becoming a useful scientific tool. Glowing patterns can reveal cryptic species, help track fish on complex reefs, and guide the search for new fluorescent proteins for medicine and biotechnology.

Since teleost fishes represent roughly half of all living vertebrate species, understanding how and where this trait evolves tells researchers where to look next. For coastal communities that depend on reefs for food, tourism, and shoreline protection, that knowledge can support smarter monitoring and protection.

The study was published in Nature Communications.