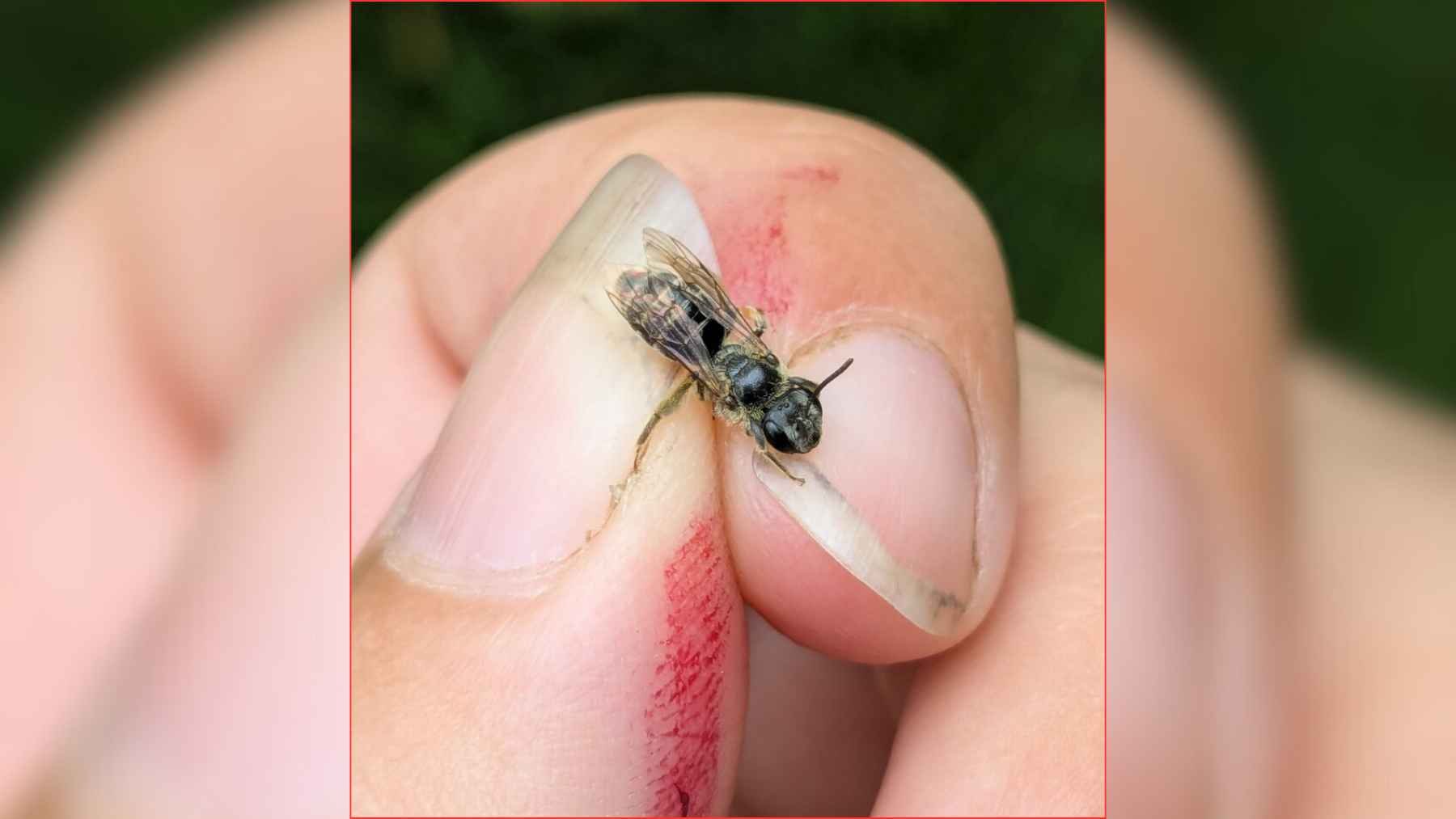

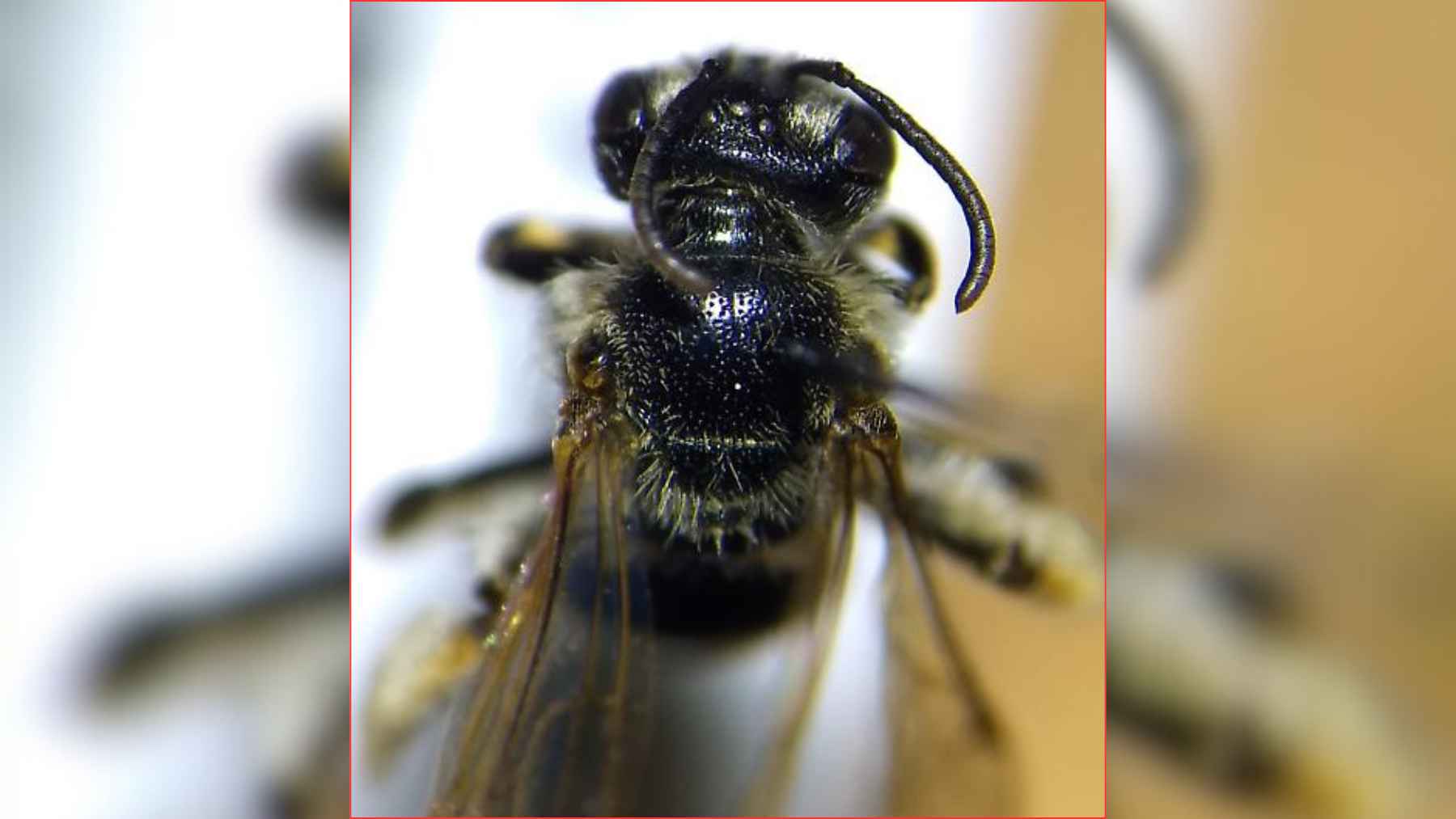

Last summer, a scientist walking through a campus orchard in Syracuse noticed a small, plain looking bee visiting the creamy flowers of young chestnut trees. At first glance it looked like any other brown bee you might brush past on a summer walk. Closer inspection showed something far more unusual, a species so rare that many experts had assumed it was gone from New York for good.

The insect was the chestnut mining bee, known to scientists as Andrena rehni, a native pollinator that depends almost entirely on chestnut and chinquapin blossoms. Its confirmed return to upstate New York links a hopeful story about species survival with a broader effort to bring back American chestnut trees to eastern forests. For a bee that had not been recorded in the state since 1904, that is no small comeback.

A chance encounter in a campus orchard

In July 2025, pollinator ecologist Molly Jacobson was collecting insects in a research orchard at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry when she netted two tiny bees on blooming American chestnut trees. Lab work confirmed they were chestnut mining bees, marking the first confirmed sighting of this species in Central New York and only the second known population in the entire state.

“This is a significant record,” Jacobson said in the college news release. She explained that finding the species in a managed orchard inside a city shows that carefully planned plantings can create real habitat for rare pollinators, even next to classrooms and traffic.

The orchard is part of the American Chestnut Research and Restoration Project at ESF, which is testing different combinations of American, hybrid, and Asian chestnut trees. For Jacobson, the surprise visitor was a living signal that these experimental groves are already starting to function as small pieces of restored forest.

A bee tied to chestnut trees

Chestnut mining bees are solitary, ground-nesting insects that specialize in one narrow kind of food. They collect pollen almost exclusively from chestnut and chinquapin flowers, then pack it into underground nests to feed their young. Their life cycle is timed to match the short burst of chestnut bloom in early summer, and they disappear from view soon after.

That tight link made the species extremely vulnerable when a fungal disease known as chestnut blight swept through the eastern United States in the early 1900s and killed billions of trees. In New York, Andrena rehni was last recorded in the southern part of the state in 1904, and the New York Natural Heritage Program later listed it as “possibly extirpated,” which means likely gone from the state.

If you picture a person who can only eat food from one restaurant, you get a sense of the bee’s challenge. When the chestnut forests vanished, so did almost all of its “menu,” and for decades no one could find the insect in New York at all.

From Hudson Valley park to Syracuse city

The story began to change in 2018, when researchers outside New York rediscovered the chestnut mining bee on chinquapin shrubs in Maryland, a close relative of the American chestnut. That single record revived interest in the species and encouraged more targeted searches in remaining chestnut groves.

In 2023, Jacobson located a population at Lasdon Park & Arboretum in Westchester County while surveying insects in a chestnut orchard there. The identification was confirmed by bee specialist Sam Droege at the USGS Native Bee Inventory & Monitoring Lab, and the find was later detailed in a 2024 study in Northeastern Naturalist co-authored with chestnut researcher Hannah Pilkey.

The new Syracuse population sits north of the Hudson Valley, a couple hundred miles beyond the older records in downstate orchards. Jacobson has said that its appearance so far from previous sightings hints that other overlooked populations may already live in chestnut plantings across the state, which would be good news for the bee’s long-term outlook.

What this tiny pollinator reveals about restoration

The ESF research station in Syracuse hosts a mix of wild American chestnuts, chinquapins, hybrids, and Chinese varieties. That mix gives scientists a rare chance to watch which trees the chestnut mining bee actually visits and to test whether it can adapt to pollen from non-native relatives of its historic host.

Jacobson notes that no nests have ever been found, so basic facts about where and how the bee raises its young are still missing.

Project director Andrew Newhouse said the rediscovery of the bee in the orchard shows that bringing American chestnut back to the landscape can help restore entire communities of plants and animals, not just a single tree species. In practical terms, that means a patch of chestnut trees behind a campus fence can quietly support insects that vanished from maps more than a lifetime ago.

ESF president Joanie Mahoney called the find proof that long-running restoration work is making a difference for a keystone tree. For most of us, bees are just a background buzz near backyard flowers or a flash of movement over a picnic table, yet discoveries like this show that rare species can survive in the same places where people study, commute, and shop.

The official press release has been published by the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry.