If you want to find our deepest relatives, you might picture fish or early land animals. You probably do not think of a tiny, transparent sea anemone that has no brain and spends its life buried in coastal mud.

Yet that unassuming animal now sits at the center of a big question about how bodies like ours first took shape.

A new study from the University of Vienna shows that a common sea anemone uses the same molecular system that many complex animals, including humans, rely on to build the axis from back to belly.

The work suggests this body building toolkit is far older than scientists once thought, reaching back roughly 600 to 700 million years, before the major branches of the animal tree split apart.

Sea anemones and humans, distant cousins with a shared plan

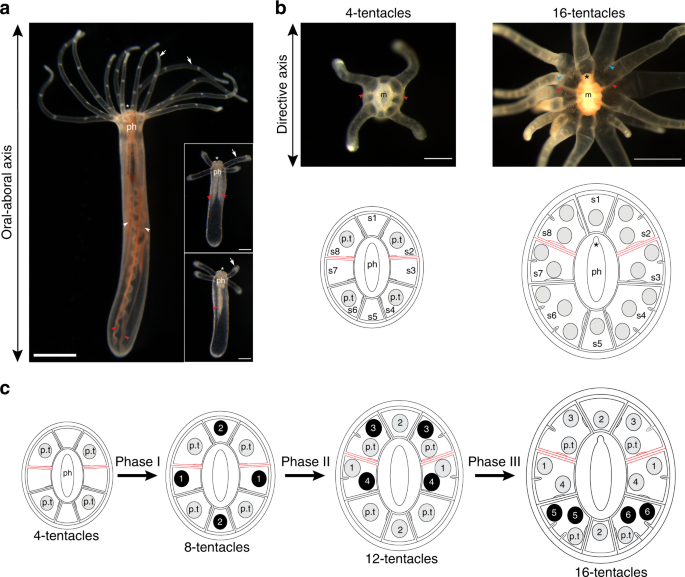

Animal life is often divided into two big groups. One group, the cnidarians, includes jellyfish, corals and sea anemones and is usually described as having radial symmetry, like a wheel or a sunflower. The other group, the bilaterians, covers most familiar animals, from worms and insects to birds and mammals, all with left and right sides, a head and a tail, a back and a belly.

On the outside, a sea anemone looks nothing like a person. It is a soft tube with a ring of tentacles at one end. No obvious front, no back, no brain. But when researchers look at gene activity inside the embryo, they see something surprising. The sea anemone quietly lays out a secondary axis that behaves very much like the back to belly axis in bilaterians.

So how does a creature that simple manage such a complex feat?

The molecular GPS that tells embryonic cells where they are

In bilaterian embryos, a family of signaling molecules called Bone Morphogenetic Proteins, or BMPs, acts like a molecular GPS for cells. Different levels of BMP tell cells what they should become. Where BMP signals are weakest, the central nervous system will form. Medium levels help mark out future kidneys. Strongest levels sit where belly skin will eventually develop.

Another protein, called Chordin, helps shape these signals. It can block BMP locally, but in some animals it also binds BMP and carries it to other parts of the embryo. Scientists call that movement BMP shuttling. Frogs and flies use shuttling. Fish, on the other hand, arrange their BMP signals without it.

Because very distant bilaterian animals share this trick, many researchers suspected BMP shuttling might be an ancient invention. The open question was whether it appeared only after cnidarians and bilaterians went their separate ways, or whether both groups inherited it from a common ancestor in the deep past.

Testing two versions of the same protein in a tiny polyp

To find out, the Vienna team turned to the starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis, a model species for developmental biology. First, they shut down production of Chordin in the embryo. Without Chordin, BMP signaling collapsed and the second body axis failed to form. That result alone showed Chordin is essential in this animal.

The researchers then brought Chordin back in two different forms. One version was fixed to the cell membrane and could not move far. The other version was free to diffuse through the embryo. Only the mobile version was able to restore BMP activity at a distance from where it was produced, which is exactly what scientists expect from a true shuttle.

In other words, the same shuttling logic that helps flies and frogs grow a back and a belly is also at work in this small cnidarian.

Lead author David Mörsdorf notes that this pattern keeps appearing in very distant animal groups. In his words, “the fact that not only bilaterians but also sea anemones use shuttling to shape their body axes tells us that this mechanism is ancient.”

Senior author Grigory Genikhovich adds that if the last common ancestor of cnidarians and bilaterians already had a bilateral body, it likely used Chordin to move BMP around the embryo and set up that axis.

A 600 million year reminder about our link to the ocean

The study does not completely settle whether bilateral body plans evolved once or several times. The authors are careful on this point, and they stress that independent evolution in different lineages is still possible.

To a large extent, though, the new data strengthen the idea of a shared, very old blueprint that later branches of life reworked in their own ways.

For everyday life, this may sound abstract. Yet it nudges how we see the living world around us. The same coastal mudflats that might look unremarkable from a boardwalk can shelter an animal carrying a molecular script related to the one that built your spine.

The corals on a reef vacation snapshot are part of the same broader group and face many of the same climate pressures as sea anemones, from warming waters to pollution.

At the end of the day, this tiny polyp is a reminder that human health, biodiversity and the history of life are closely entangled. Protecting marine ecosystems does not only save charismatic wildlife. It also preserves living archives of how complex bodies first emerged on Earth.

The study was published on Science Advances.