A galaxy that lived only about 930 million years after the Big Bang looked, at first glance, like a smooth rotating disk. Then astronomers zoomed in with sharper tools and found something very different, a “bunch of grapes” made of many compact star-forming clusters inside one galaxy.

The discovery, led by Seiji Fujimoto of the University of Toronto, is pushing scientists to rethink some basic assumptions about how early galaxies grew. If one “normal” young galaxy can hide this much internal structure, how many others have been fooling us too?

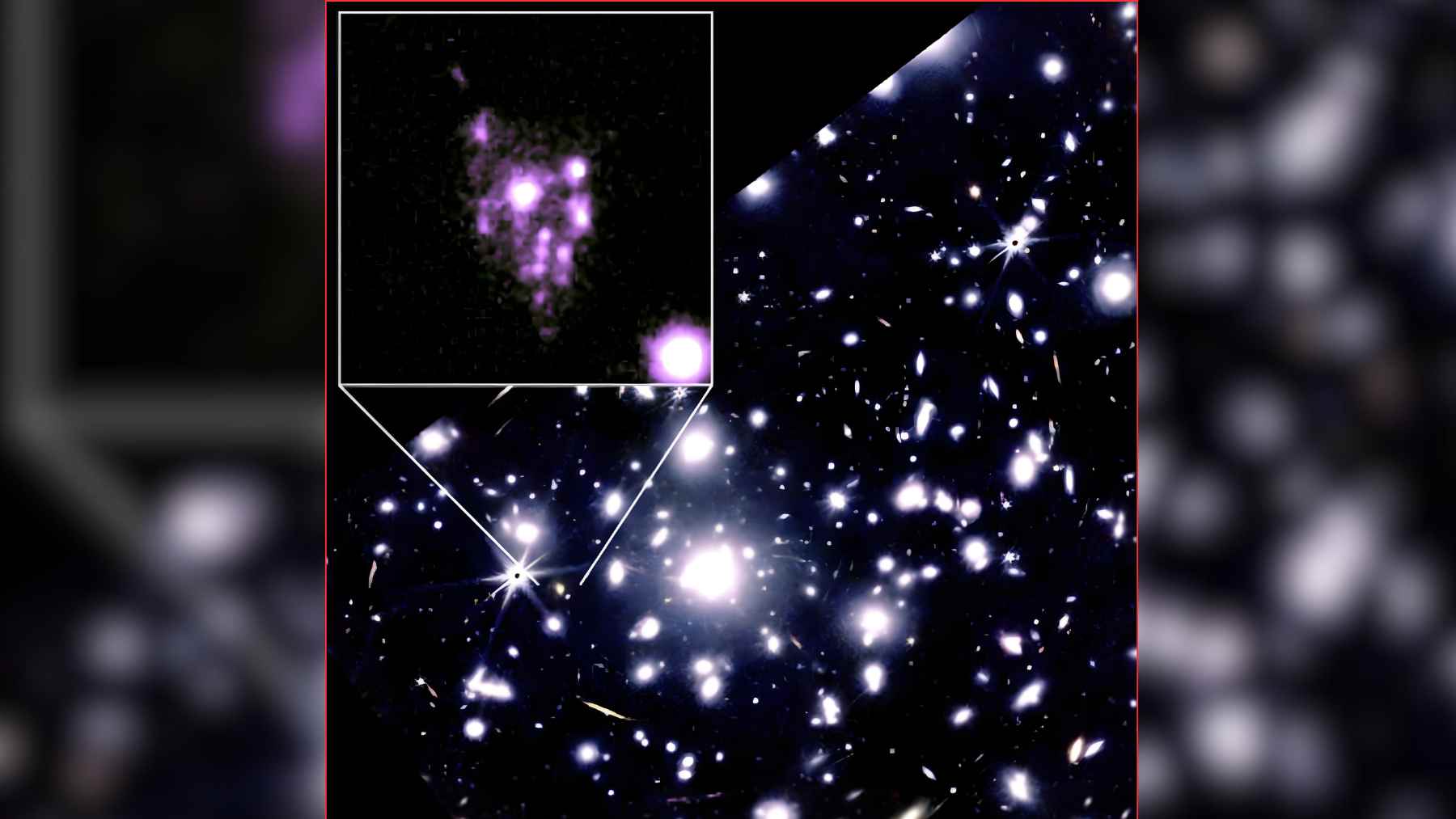

A faint galaxy gets a huge assist from gravity

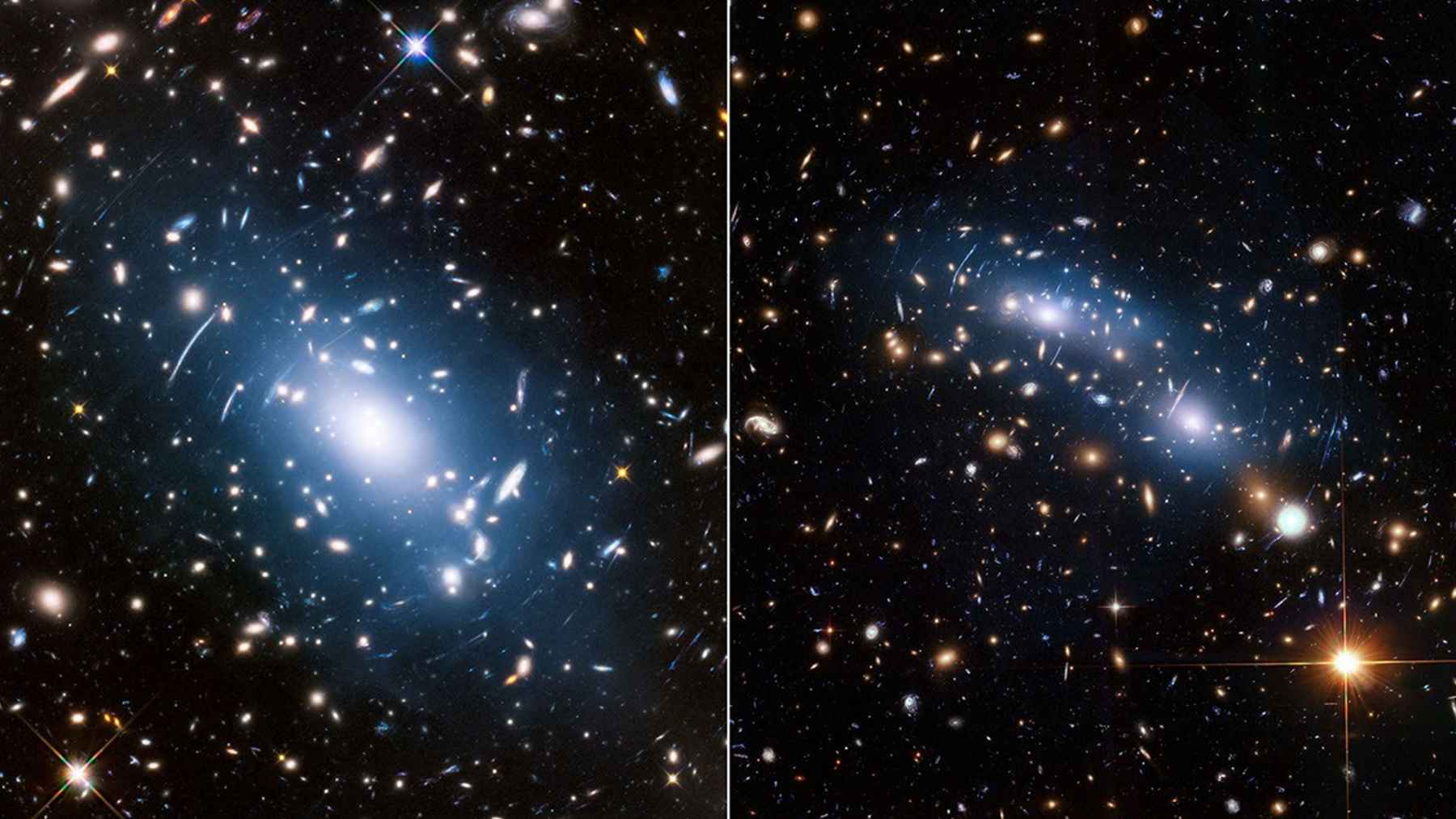

The key trick is gravitational lensing, where a massive object bends and amplifies light from something behind it, almost like nature built a giant magnifying glass. In this case, a foreground galaxy cluster boosted the view enough to reveal details that would normally be too small and dim to spot.

That boost mattered because faint early galaxies are usually the hardest to study. The target was first identified through the ALMA Lensing Cluster Survey, then followed up with more than 100 hours of observations to squeeze out as much detail as possible.

What the team actually saw

Earlier images from the Hubble Space Telescope made the galaxy look fairly smooth, like a simple disk. With higher-resolution observations, that “smooth” look broke apart into at least 15 compact, star-forming clumps packed into the same rotating system, giving it the nickname “Cosmic Grapes.”

These clumps are dense regions where stars are forming fast, the kind of places that can dominate a galaxy’s glow. The Nature Astronomy paper reports that the clumps account for roughly two-thirds of the galaxy’s ultraviolet light, meaning a lot of the starlight comes from these tight hotspots rather than from a uniform spread of stars.

A rotating disk that should not be that lumpy

There’s another twist that makes this more than a pretty picture. Gas measurements show the galaxy is rotating in an organized way, with one side moving away and the other side moving toward us, the classic signature of a spinning disk.

That combination is what raised eyebrows. Many computer simulations struggle to make a young, faint galaxy that is both smoothly rotating and packed with so many star-forming clumps, which hints that something in the “usual” recipe may be off.

Why this changes the hunt for cosmic dawn

Researchers emphasize this is not being treated as a rare, extreme oddball. The team describes it as a typical early galaxy by measures like mass, size, and star formation activity, which suggests the same hidden clumpiness could be common.

In practical terms, that means some galaxies that look calm and featureless today may just be unresolved, like a blurry phone photo before you tap to focus. Future observations will test whether “Cosmic Grapes” is a one-off curiosity or the first clear example of a broader pattern.

The bigger picture for galaxy formation models

One likely pressure point is “feedback,” the energy and force from events like supernova explosions that can blow gas around and limit star formation. The new results point to feedback being weaker than many models assume, letting gas stay clumpy and keep forming stars in compact pockets.

As Fujimoto put it, “It was truly astonishing” to see so many clumps inside a galaxy that still rotates smoothly. That kind of tension between observations and simulations is often where astronomy moves fastest, because it forces the next generation of models to match what the universe is actually doing.

The main study has been published in Nature Astronomy.