A law meant to keep Virginia wine truly Virginian is now sending ripples through the hills of Loudoun County and beyond. As Senate Bill 983 moves from paper to practice, some of the state’s smallest wineries say they may have to shut their doors.

Wine is serious business in this corner of the United States. Loudoun County alone counts about fifty wineries and produces more grapes than any other region in Virginia, with wine-driven tourism bringing in an estimated $4.9 billion last year.

Those vineyards are not only weekend backdrops for engagement photos and bachelorette parties. They are working landscapes that help keep open space from turning into parking lots and subdivisions.

The new law, approved in 2023, reshapes who can call themselves a farm winery and what that license allows them to do. On paper, the aim is straightforward enough. Protect the integrity of Virginia wine by making sure bottles labeled as local really do come mostly from local fruit. In practice, the picture is more complicated.

A wine rule built around local grapes

Senate Bill 983 requires every farm winery license to fit into one of four classes that link legal privileges to where grapes and other fruits are grown and how much land sits under vine.

Under the rules for Class I, all of the fruit used to make wine must be grown or produced on the licensed premises, and the winery has to maintain at least one and a half acres of active growing area on site. Class II license holders must grow at least 51% of their fruit on property in Virginia that they own or lease, can rely on no more than 25% from outside the Commonwealth, and need at least three acres planted at the winery itself.

Classes III and IV are built for larger operations. They still require at least 75% Virginia-grown fruit, set minimum volumes for wine fermented on the premises, and in the case of Class IV demand at least ten acres under cultivation and a long track record as a licensed farm winery. Fees rise with each step, from a few hundred dollars a year for the smallest farm wineries to several thousand for the largest.

Supporters say tying the license to real farming reduces the temptation to truck in bulk juice from far away, bottle it under a picturesque Virginia label, and call it a day. From a climate angle, that idea makes sense to a large extent, since shorter supply chains can shrink transport emissions and keep more of each wine dollar flowing through rural communities.

Small wineries caught in the middle

Not every winery, though, sits on a postcard perfect estate with rows of vines right outside the tasting room. Some of the most characterful small producers work with leased vineyards scattered across the countryside or supplement their own grapes with fruit from neighboring states when harvests come up short.

Bill Hatch from Zephaniah Farm Vineyard in Loudoun County told local reporters that in the past it had become very easy to build a business around buying grapes, juice or even finished wine instead of growing the raw materials on site. He welcomed efforts to curb that model, which barely touches the soil, but acknowledged that the new thresholds put real pressure on producers who do farm yet lack enough contiguous acreage.

Bacchus, a Fredericksburg winery that also taught people how to make their own wine, is closing its current doors and relocating, in part because of the new regulations. Owner Hal Bell warns that many boutique wineries already live very close to the edge and cannot simply buy more land, plant vines, then wait years for usable grapes while the electric bill and labor costs keep arriving every month.

In his view, if too many of these small players vanish, Virginia risks losing an entire layer of diversity in its wine landscape.

Environmental stakes behind the legal fine print

From an ecological point of view, there is a genuine balancing act. Requiring more fruit to come from Virginia soil can support farm jobs, preserve open vistas and reduce the miles that heavy trucks travel with chilled grapes or bulk wine. On the other hand, strict acreage thresholds may tilt the playing field toward larger estates that can afford more land, irrigation systems and machinery.

Smaller wineries are often the ones experimenting with organic or low-input practices, cover crops between vine rows and hardy grape varieties that cope better with heat and drought. If those innovators disappear, the region could drift toward more uniform, chemically intensive vineyards, which would work against the idea of truly sustainable local wine.

The law does build in some flexibility for bad years. Under section 4.1 219 of the Virginia Code, state agriculture officials can petition for temporary relief when frost, disease or extreme weather sharply reduce local harvests, allowing wineries for a given license year to use more fruit from outside Virginia or from beyond their own fences.

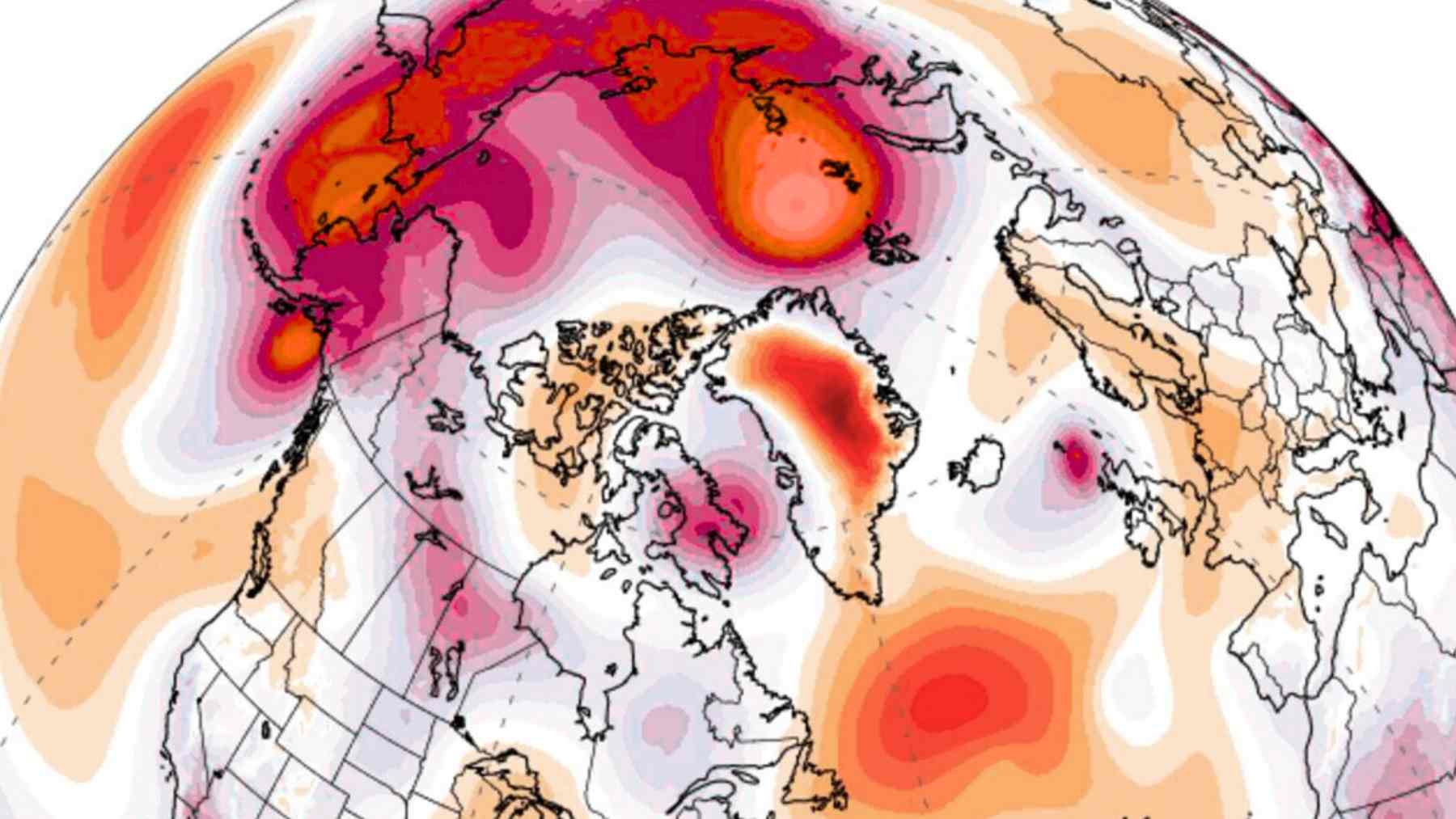

With climate change bringing more unpredictable springs and sticky summer heat, that safety valve will likely be tested.

What Virginia wine drinkers can watch for

For the most part, the new system is already in place. Existing farm wineries that applied before July 2023 and had licenses granted before the start of 2024 have a grace period that runs until July 2028, after which the stricter acreage and sourcing rules apply to them as well. Others are already navigating the tighter standards.

So what should environmentally-minded wine drinkers keep in mind? One simple step is to ask where the grapes were grown and how the vineyard is managed. Another is to pay attention to the small names on tasting room boards. If those independent producers fade away, the rolling green hills of Virginia wine country may remain, but the voices pushing the sector toward a more resilient and sustainable future could grow much quieter.

The official statement was published by the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority.