Picture 2,000 dead rodents, each carrying a small tablet of paracetamol, drifting into tropical treetops on tiny paper parachutes. That surreal image comes from a real operation on Guam, where United States agencies are using a common painkiller as a highly selective poison against invasive brown tree snakes that have devastated local wildlife and even knocked out power across the island.

For years, scientists with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and its USDA Wildlife Services program have tested baits laced with 80 milligrams of paracetamol, also known as acetaminophen, a dose that kills brown tree snakes but leaves most other animals largely unaffected.

The latest wave of about 2,000 poisoned carcasses is part of an automated aerial system that now supports ongoing snake control in Guam’s forests, meant to protect remaining native wildlife and stabilize the island’s fragile power grid for more than 150 thousand residents.

An unusual weapon in Guam’s forests

Invasive brown tree snakes probably reached Guam after the Second World War hidden in cargo, then spread across nearly every patch of forest in just a few decades. Without natural predators and with plenty of prey, their numbers climbed to an estimated 50 to 100 snakes per hectare in some areas, which helped drive most of the island’s native forest birds toward local extinction.

Biologists say the island may now hold close to two million snakes, a striking figure on land about the size of a small county in the mainland United States. Wildlife researcher Shane R. Siers and colleagues have shown that traditional methods like traps, barriers, and hand capture alone cannot keep those numbers down across an entire landscape, which is why aerial toxic baits have become such an important extra tool.

How the paracetamol bait system works

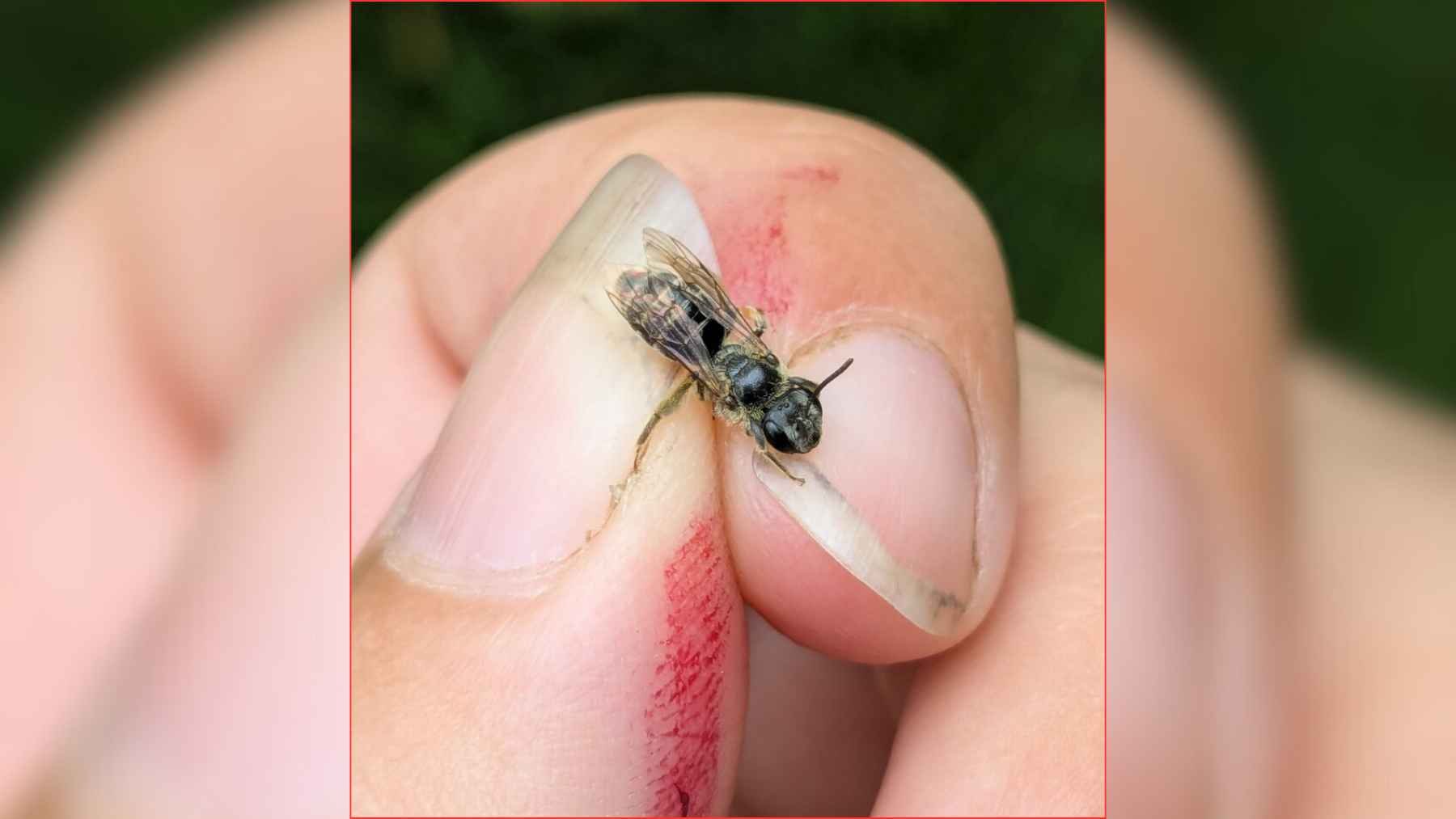

Dropping painkiller-laced bait sounds risky, yet the science behind it is surprisingly precise. Laboratory and field tests found that brown tree snakes are extremely sensitive to oral doses of acetaminophen, with a single 80-milligram tablet hidden in a dead rodent causing very high mortality, especially in medium and large snakes that eat the most birds.

Environmental toxicologist Peter van den Hurk at Clemson University and his team have linked that vulnerability to the snakes’ limited ability to break down the drug, which leads to rapid damage in their red blood cells and liver. In humans the same amount is similar to a standard children’s dose, but in these reptiles it is often fatal within a few days.

To get the toxic bait into the canopy, researchers attach each carcass to a small cardboard device with a long paper streamer that works like a mini parachute and tends to snag in branches instead of falling to the ground where other animals might reach it. In trial drops, a subset of baits carried tiny radio transmitters so teams could track which snakes found them and how far they moved before dying, a way to check that the method works as intended.

The scale of the brown tree snake problem

Brown tree snakes have reshaped Guam’s ecosystems in ways residents can hear the moment they step into the forest. Studies by United States researchers report that the snakes have eliminated most of the island’s native forest birds and many lizards, in some cases removing more than three quarters of the original species and leaving once noisy jungles unnervingly quiet.

The damage does not stop with wildlife. Research by herpetologist Thomas Fritts for the U.S. Geological Survey showed that snakes caused more than 1,600 power outages between the late 1970s and late 1990s, with recent years averaging close to 200 outages annually and economic losses of at least $4.5 million per year before even counting broken equipment.

For people living on the island, that means spoiled food in refrigerators, stalled businesses, and long, humid nights when the air conditioners shut off after a snake shorts out a transformer. Local utilities such as Guam Power Authority have worked with federal agencies to harden key parts of the grid, yet the reptiles still slither onto poles and lines in surprising numbers.

What happens next for Guam and its snakes

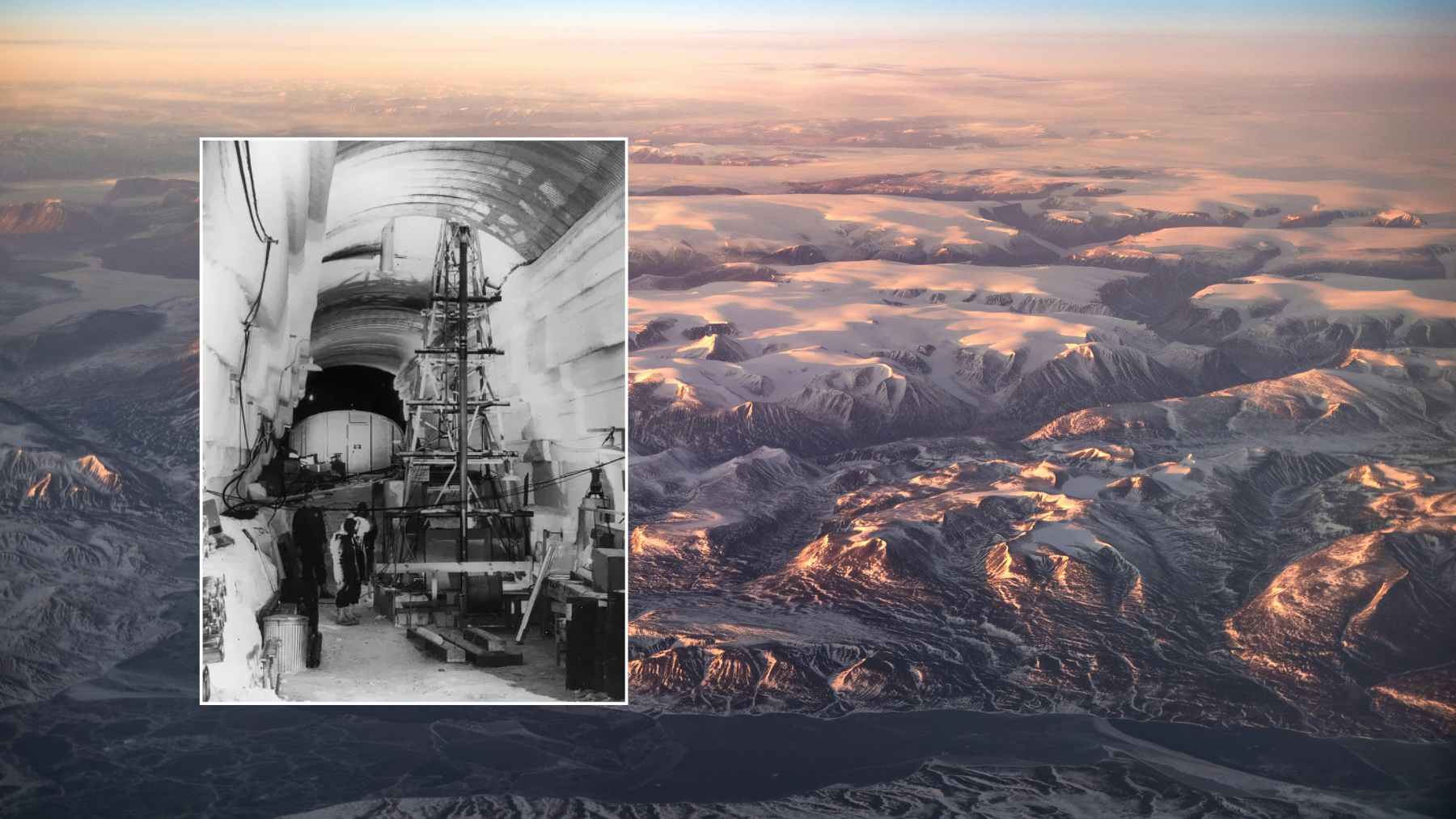

To move beyond small tests, USDA engineers and biologists worked with private designers to create an automated aerial delivery system that loads bait cartridges into a helicopter-mounted dispenser and releases them across the forest at a rate of several per second.

A 2019 field evaluation published through the International Union for Conservation of Nature reported accurate placement of baits and canopy entanglement in roughly two thirds of drops, a key step in shifting the system from experimental trials to regular operations.

In fenced habitat management units on Andersen Air Force Base, conservation teams with Joint Region Marianas now combine aerial baiting with trapping, snake detecting dogs, and physical barriers to protect patches of forest where rare birds might one day be reintroduced.

Officials say the paracetamol program can sharply lower snake numbers for months at a time inside treated areas, yet reinvasion from surrounding forest still occurs, which means repeated applications and a mix of tools remain necessary.

At the end of the day, aerial paracetamol baits are one more tool rather than a final cure, and modeling studies suggest they can cut snake activity by around 80% in treated plots without wiping out the island wide invasion. Other islands at risk, from Hawaii to parts of the Galápagos, are watching Guam closely as they weigh how far to go in using similar methods against invasive reptiles.