More than a thousand years ago, red auroras flickered across the sky after a powerful solar storm hit Earth. That same storm quietly imprinted extra radioactive carbon into tree rings. Today, that cosmic fingerprint has allowed scientists to show that Vikings were cutting timber at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland in the year 1021, the earliest securely-dated European presence in the Americas.

It is a striking mix of space physics and old wood. Instead of relying only on legends about Vinland, researchers can now point to a specific year when Norse sailors turned a windy Canadian headland into a small base camp.

Viking turf houses on a northern shoreline

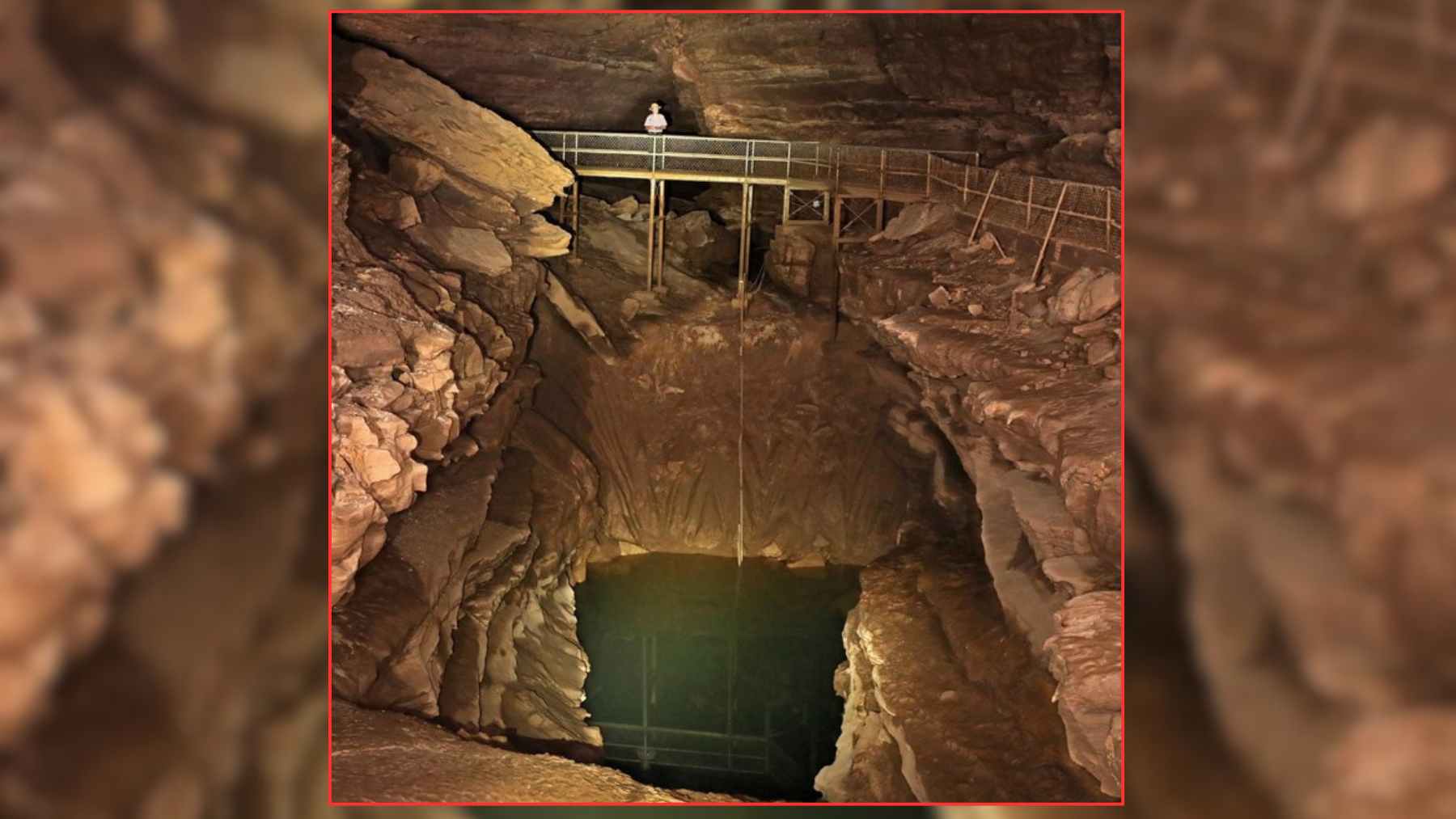

Perched at the tip of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula, L’Anse aux Meadows holds the remains of turf-walled, timber-framed buildings that match Viking houses in Iceland and Greenland. Finds of iron nails, a forge and woodworking areas all point to a short-lived Norse settlement.

For years, radiocarbon dates from the site were too imprecise, spreading across most of the Viking Age. The Icelandic sagas did speak of voyages to a western land rich in timber, but those texts were written down long after the events they describe, so the timelines stayed fuzzy.

How a cosmic burst became a time stamp

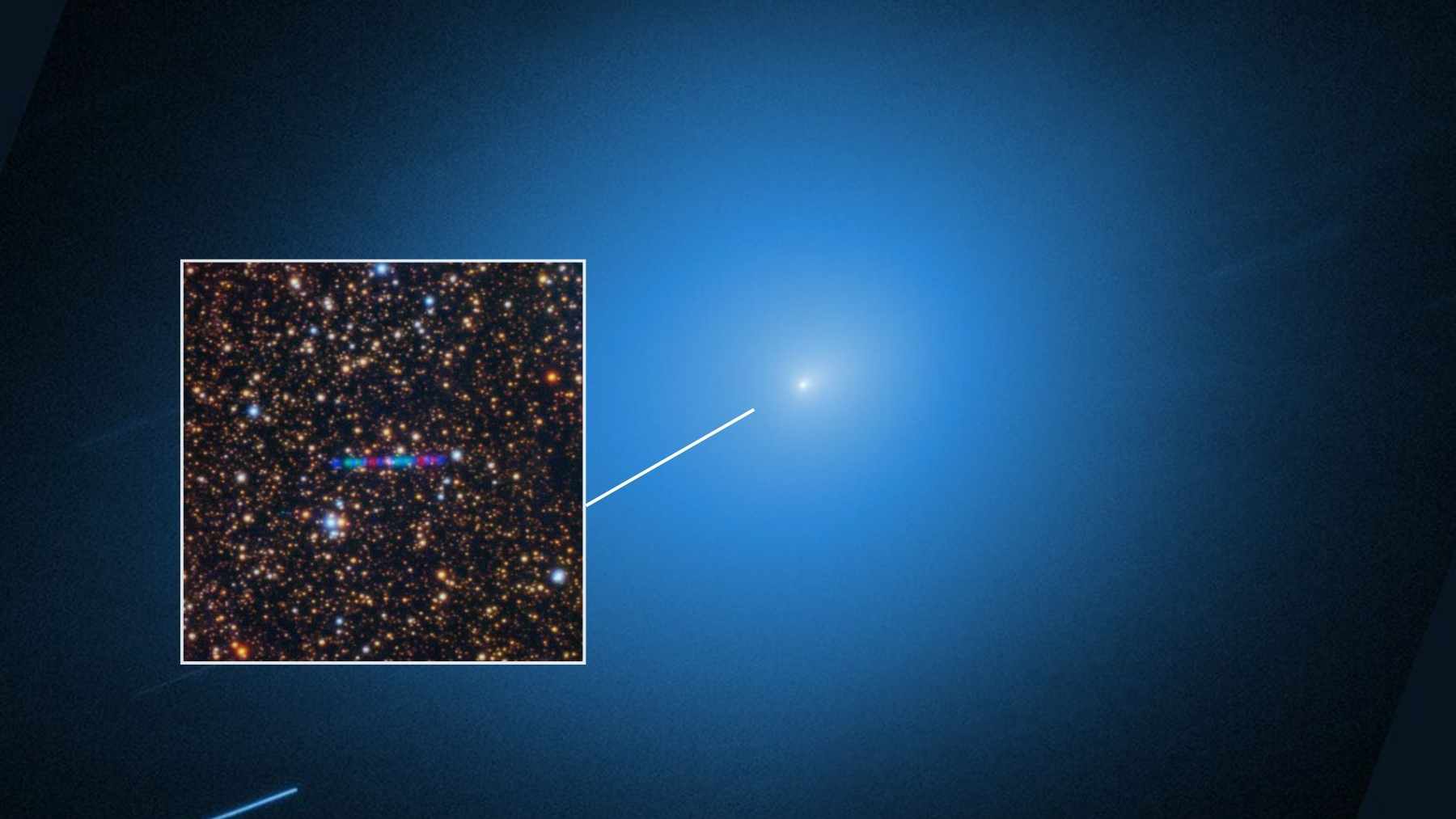

In the years around 993, an extreme outburst of radiation from the Sun struck Earth. The event boosted the level of carbon 14 in the atmosphere, so trees growing at the time created one unusually “hot” ring that can be spotted centuries later in the lab.

Michael Dee and his team sampled thin slices from four pieces of Norse worked wood at L’Anse aux Meadows. Three still preserved their outer ring and the clean cuts of metal blades that local Indigenous toolkits did not produce.

Tracking radiocarbon ring by ring, the researchers found the 993 spike, then counted twenty eight rings to the bark edge. In every sample, that outer ring formed in 1021.

That agreement across three different trees makes driftwood or coincidence very unlikely. The authors argue that 1021 is “the only secure calendar date for the presence of Europeans across the Atlantic before the voyages of Columbus”, a rare exact year in early global history.

Early globalization and Arctic ecosystems

To a large extent, that one date fits with a bigger picture of Norse expansion across the North Atlantic. Ancient DNA from walrus skulls shows that Viking traders were tapping ivory from herds in northwest Greenland and Arctic Canada and shipping tusks thousands of kilometers to markets in Europe and perhaps the Middle East.

Those routes would have brought Norse sailors into regular contact with Indigenous Arctic communities.

That trade came at a cost for wildlife. By the Norse period, over-hunting had already wiped out walrus in some regions, and new work suggests early commercial hunting in Iceland and Greenland was probably unsustainable, driving hunters toward ever more remote, fragile ecosystems.

Tree rings, solar storms and our vulnerable tech

Tree rings do more than track axes and trade routes. They also record our planet’s dance with the Sun. Scientists have identified several sharp radiocarbon spikes, called Miyake events, including one ancient storm that appears to be the largest yet seen. A similar blast today could damage satellites and knock out power grids, with costs that would ripple through phones, internet links and household electric bills.

So a scrap of Viking wood becomes more than a museum curiosity. It turns into proof that cosmic storms can pin down single years with remarkable precision and that those natural events ripple into human history and climate science alike.

What happens next? Archaeologists are combining classic excavation with satellite imagery and other remote sensing tools to scout more of the Newfoundland and Labrador coast for subtle soil marks and mounds that might signal short lived Norse camps.

One much-discussed candidate at Point Rosee ultimately showed no evidence of Viking presence, a reminder that progress often comes with dead ends along the way.

At the end of the day, the story is surprisingly simple. Sailors from the North Atlantic crossed an ocean, built houses on a wild Canadian headland and left behind a few planks of wood. A thousand years later, a burst of energy from the Sun helped us find them again and fix that moment on a precise calendar line.

The study was published in Nature.