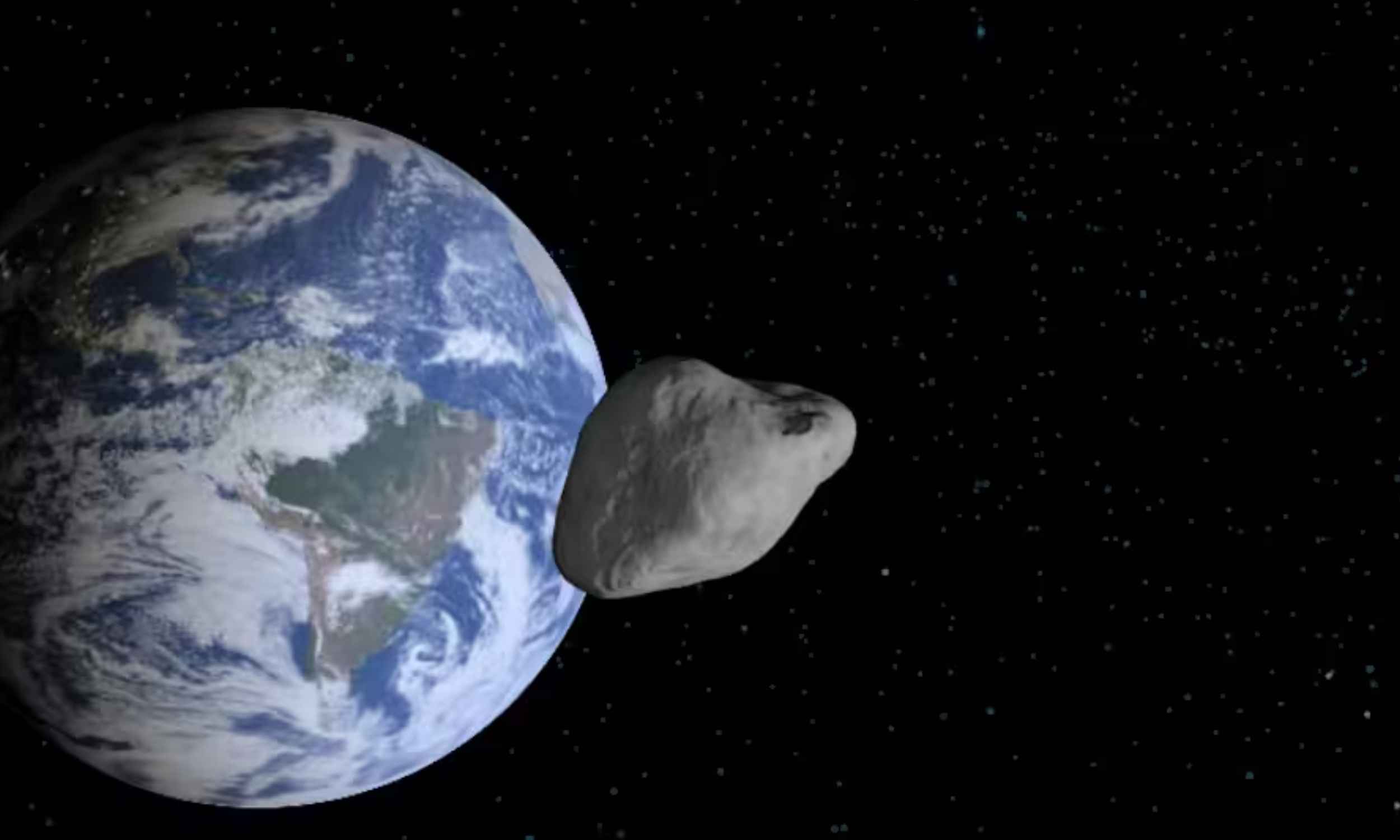

For over a century, we believed the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy were destined for an epic encounter, a collision capable of completely reshaping our corner of the universe. Since 1912, this prediction has been part of both science and popular imagination: two giant spirals, separated by 2.5 million light-years, traveling toward each other at about 100 kilometers per second. So much so that the impact, estimated to occur in 4.5 billion years, seemed inevitable. But astronomy has a knack for subverting expectations.

Milkomeda: Cosmic fireworks or a quiet end for our galaxy?

The traditional theory stated that, upon colliding, the Milky Way and Andromeda would merge into a single cosmic body: the so-called “Milkomeda”. This process would destroy the spiral shapes of both, transforming them into an elliptical galaxy. Carlos Frenk, a professor at Durham University in England, describes the classic scenario this way:

“Collisions between other galaxies have been known to create ‘cosmic fireworks,’ when gas, driven to the center of the merger remnant, feeds a central black hole emitting an enormous amount of radiation, before irrevocably falling into the hole.”

Interestingly, even in such a massive event, the probability of direct collisions between stars is minimal. Earth’s fate, in this scenario, would not be sealed by a galactic merger, but rather by the end of the Sun’s life cycle, predicted to occur in 5 billion years, when it will expand into a red giant.

Local giants reshape cosmic fate: Will the Milky Way collide or dodge disaster?

Until a new study, published in Nature Astronomy, went beyond analyzing the Milky Way and Andromeda as isolated systems. So much so that, for the first time, astronomers incorporated other “major players” in the Local Group into the calculation, such as the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) and M33 (the Triangulum galaxy). Till Sawala of the University of Helsinki summarizes the impact of these presences:

“The extra mass of Andromeda’s satellite galaxy M33 pulls the Milky Way a little bit more towards it. However, we also show that the LMC pulls the Milky Way off the orbital plane and away from Andromeda. It doesn’t mean that the LMC will save us from that merger, but it makes it a bit less likely.”

100,000 simulations were run, considering 22 different variables (masses, velocities, positions, and uncertainties). And the result was clear: the chance of a collision between the Milky Way (which may be broken, according to other research) and Andromeda in the next 10 billion years is approximately 50%. And the predicted encounter in 4 to 5 billion years has dropped to just a 2% probability.

Milky Way’s fate: Collision, close call, or cosmic makeover?

Here’s the scientists’ big revelation: there’s no certain fate for the Milky Way. This is because half of the simulations indicate that we could pass close to Andromeda, exchange “gravitational brushes,” and then separate. In the other half, the collision still occurs, but in a longer timeframe and with different details than previously predicted. So far, we have two possible scenarios:

- Delayed collision: The galaxies approach each other, lose orbital energy, and collide after 7.6 to 8 billion years.

- Mutual survival: The closest approach is close enough that the gravitational force does not cause a merger.

A merger with the LMC is considered virtually certain in about 2 billion years. Frenk says: “The Milky Way has a greater chance of colliding with the LMC within 2 billion years, which could fundamentally alter our galaxy.” The study makes it clear that even with the best current data, the fate of the Milky Way remains “completely open.” However, what we already know is that the Milky Way is heading toward a strange region of the universe.