Five thousand years ago on a low plateau outside what is now Seville, someone poured astonishing time and energy into a single idea. Dress a small group of women in garments made from the sea itself.

Archaeologists have now counted around 270,000 tiny beads from the Montelirio tholos burial at Valencina, most of them carved from local marine shells and sewn into full-length tunics worn by women of clear high status.

It is the largest bead assemblage ever found in a single tomb and it strongly suggests that power in this corner of Copper Age Iberia often rested in female hands.

A wearable monument built from the coast

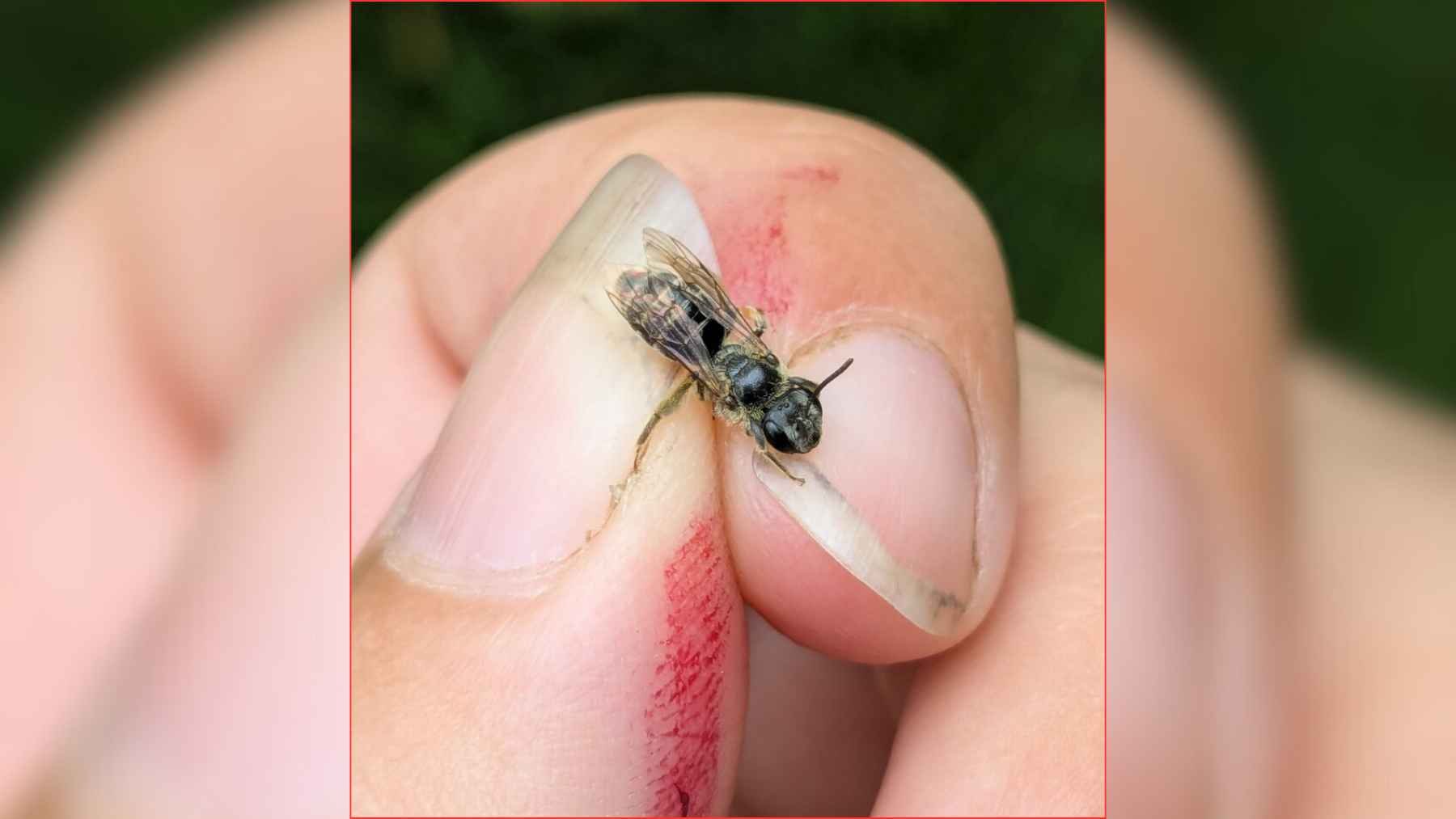

The beads are small, only a few millimeters wide, yet together they represent almost a metric ton of raw shells gathered from ancient beaches in the lower Guadalquivir area. Researchers estimate that at least eighteen thousand scallops and cockles were needed, adding up to more than eight hundred kilograms of shell before any cutting or polishing even began.

Then comes the real work. Experimental archaeology showed that shaping and perforating a single shell bead can easily take many minutes, even in trained hands.

Scaled up to the full Montelirio collection, that means tens of thousands, perhaps nearly a quarter of a million hours of focused craft. Imagine ten specialists working full time for months on end, doing little else.

People who live on the edge of subsistence do not divert that much labor into jewelry. A project like this only happens in a community with surplus food, organized production, and leaders who can direct skilled hands toward a shared symbolic goal.

Women at the center of a coastal mega site

Inside Montelirio, the beads were not scattered. They formed complex garments worn by at least several women, including Individual UE343, a young adult placed in the main chamber with arms raised in an “orant” posture that looks like prayer. Her body lay exactly where a narrow shaft of sunlight touches the floor during the summer solstice, in front of a clay stela that dominated the room.

Most of the people identified in the burial are women, and the most elaborate beaded outfits belong to those in their late twenties and early thirties. That age pattern hints at a kind of seniority, perhaps similar to how we still look to experienced adults when something important needs to be blessed, signed, or decided.

Montelirio is not an isolated curiosity. It is part of the huge Valencina Copper Age mega site, where new bioarchaeological work points to a surprisingly fluid society with limited sharp hierarchy and a notable presence of female leaders.

Just a short distance away lies the grave of the so-called Ivory Lady, another outstanding female burial that predates Montelirio and seems to have remained a focus of offerings for generations. The web of connections between the two tombs looks very much like a long-lived line of influential women.

Clothing that carried a worldview

What exactly were these garments made of? The beads themselves come mostly from scallop and cockle shells, species that still live today along the Atlantic coast. Their bright, pale surfaces would have caught the light inside the tomb and in any public rituals that took place while the women were alive.

Microscopic plant remains trapped in some beads show traces offl ax fibers, which suggests that the shells were sewn onto linen-based textiles that wrapped the body from shoulders to feet.

Add in the red glint of cinnabar, a mercury-rich mineral sprinkled generously in the tomb, and you get a striking color palette. White, red, and touches of green from stone beads and ivory or amber pendants shaped like acorns or birds. It must have been hard to look away when one of these women stepped into view.

From an environmental angle, the outfits tell a quiet but powerful story about people who knew their coast intimately. They relied on ordinary, local shells rather than exotic stones brought from far away.

At the same time, the sheer quantity of material shows that near-shore ecosystems were already woven into complex social and ritual economies. Today we worry about overfishing and habitat loss in those same waters. Back then, the sea was already a political and spiritual partner, not just a pantry.

What this means for us now

For the most part, modern readers meet the Copper Age through copper axes and stone monuments. The Montelirio beads shift that picture. They highlight textiles, patient craft, and the bodies of women as key places where power was built and displayed.

They also remind us that every piece of status clothing, from designer sneakers to ceremonial robes, rests on real landscapes and real labor.

Next time you walk a beach and see broken shells at your feet, it is worth pausing for a second. Five thousand years ago, those same kinds of shells helped anchor a community, honor its leaders, and materialize a worldview in which the sea, the sky, and human identity were tightly stitched together.

The study was published in Science Advances.