Solar energy obtains revolutionary improvements through ultra-light solar cells that function internationally. The cells demonstrate 400 times better performance than normal solar panels, although they maintain half the thickness of a single hair strand. The discovery enhances operational efficiency as well as general applicability. The article examines the scientific basis of ultra-light solar cells and demonstrates their present applications alongside possible future developments. The advanced cells serve as a potential solution to transform renewable energy by providing flexible, lightweight installations in different settings, which include rooftops and spacecraft.

It can sit on a soap bubble—here’s why this solar cell is unlike anything before

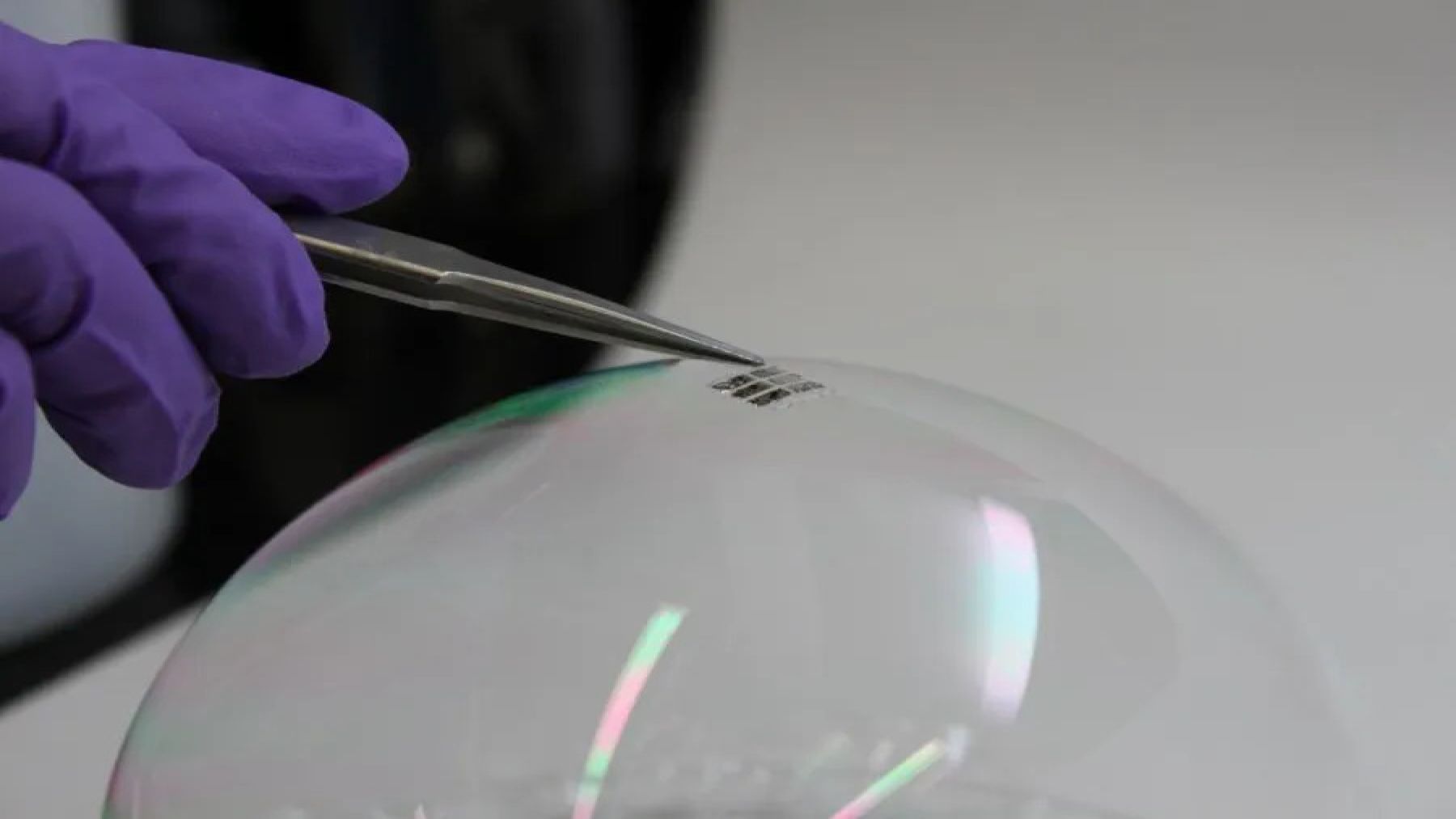

Professor Vladimir Bulović at MIT developed an incredibly lightweight solar cell that stays buoyant on top of soap bubbles because of its delicate nature. The achievement became possible by replacing conventional heavy substrates with perylene, which offers lightweight flexibility.

The solar cell reaches 2.3 micrometres in thickness because researchers developed a special room-temperature fabrication method to protect the fragile material. The new lightweight solar panel technology offers an installation method like unfolding an adhesive sheet that can bond to any surface(this solar breakthrough will amaze you).

400 times more energy per gram—why this solar technology is changing everything

Through their progressive solar technology, ultra-light solar cells have revolutionized energy efficiency standards. Such solar cells produce 6 watts of power per gram, yielding 400 times higher efficiency than typical solar panels. Fabrication techniques enable the efficient solar cell material deposition process, which happens inside vacuum chambers when material receives treatment on perylene surfaces. The production technique enables a lightweight, robust design that transforms solar power collection technology.

These solar cells function with great versatility and high operational efficiency. Ultra-light materials render them appropriate for essential applications that need to maintain low weight criteria. The weight reduction needs of space exploration require lightweight components; therefore, these cells demonstrate the optimal solution. The cells deliver extensive advantages in portable electronic systems that produce maximal power without enlarging their footprint.

Sunlight-powered solar cells demonstrate high durability and flexibility, which creates fresh opportunities for power production. Their special design enables them to function efficiently on diverse surfaces, ranging from flexible wearable devices to drones and other applications. These cells could establish a vital position in future renewable energy systems because research continues to protect renewable energy through efficient solar power while improving accessibility.

You won’t believe the places where these solar cells can be used.

Because of their flexible design, ultra-light solar cells have multiple adaptable uses. Their slender construction and flexible design let them become embedded within clothing textiles and balloons, paper sheets, and human epidermis, thus enabling their use. The innovation introduces flexible embedded power systems integrated with modern products, establishing new possibilities for solar energy utilization. The cells form a new aggregate with transparent solar panels, which simultaneously produce energy without affecting the visual appeal of glass surfaces.

The new technology breakthrough introduces remarkable opportunities for renewable energy development for future applications. People can expect to power their equipment using their clothing and extract energy from common household objects without requiring bulky solar panels. These solar cells achieve full-scale integration with surfaces to boost convenience and bring revolutionary changes to wearable embedded solar technology.

Mass production hurdles—but here’s why this tech will soon be everywhere

The deployment of these ultra-light solar cells faces obstacles that must be overcome to achieve widespread commercial success. The mass production of solar cells requires a speed upgrade from their existing manufacturing method. Research teams are investigating multiple materials for substrates because they aim to boost the strength and operational lifetime of these cells for dependable performance. Scientists expect this technology to become widely available over the next decade, even though they must overcome certain obstacles.

Renewable energy received an enormous breakthrough with the development of ultra-light solar cells. Because of their unique efficiency characteristics, these cells can transform solar power utilization methods on a broad scale in forthcoming years. Research advances in the present day will make solar power technology shine brighter than anticipated for the future(This innovation is changing everything!)