An Indiana visitor returned to Arkansas’s Crater of Diamonds State Park and spotted a white diamond weighing 2.71 carats. That is about 0.019 ounces, a tiny weight for a big moment in a public search field.

The gem turned up in the Canary Hill area during a second stop on the couple’s road trip. Staff confirmed the find at the park’s identification table in Murfreesboro, Arkansas.

What the find tells us

White worked by dry sifting, breaking up soil by hand through mesh screens, and he focused on subtle differences in luster and shape. He had been checking quartz and calcite, then noticed a glimmer that stood out.

“It looked like a metal piece of glass,” said Dewy White. He recognized it immediately and hurried it to staff for verification.

Geologist J. M. Howard of the Arkansas Geological Survey (AGS) has mapped the park’s volcanic pipe and explained how weathering exposes diamond bearing rock near the surface. His field work helped clarify why a careful eye can still find natural crystals on plowed ground.

The park reported the gem as the fourth largest registered there this year. Persistence and patient sorting mattered more than fancy gear on this search.

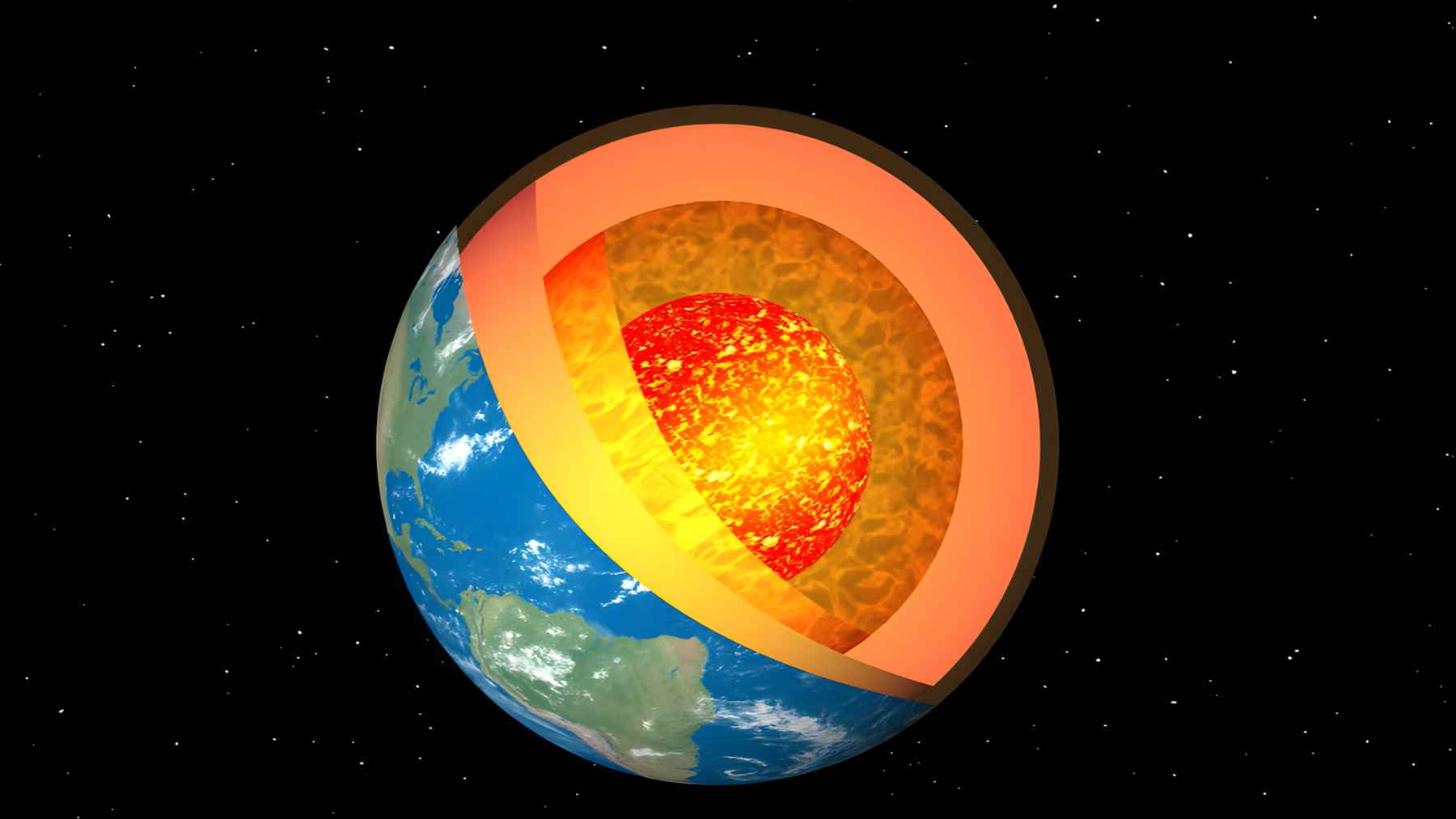

How diamonds reach the surface

Diamonds at Murfreesboro rise in a rare volcanic rock called lamproite, an unusual, potassium rich mantle melt that can carry deep minerals toward the surface. The rock formed a pipe when gas charged magma blasted upward and cooled.

That pipe, called a diatreme, a steep volcanic vent widened by explosions, eroded into a shallow field over millions of years. Gentle erosion, measured in only about 165 feet here, left upper layers preserved well enough for visitors to search today.

Hunting rules and odds

The park’s plowed search field spans about 37 acres, the eroded surface of an ancient crater where visitors can look for diamonds on their own. The park is one of the few sites where the public can search source rocks for natural diamonds.

Finders keep what they find under a simple policy. Staff provide free checks at the identification table, which keeps the process transparent and consistent.

From shovel to lab

Park interpreters teach visitors to watch for rounded edges, a metallic luster, and a slick surface that does not sparkle like faceted gems. Most stones discovered here are white, with brown and yellow also turning up in smaller shares.

Those color patterns match what staff report from certified finds at the site. The park lists typical hues and recent recoveries on its page.

Why this park stands out

A 2025 study examined 155 diamonds from the Prairie Creek lamproite and found spectroscopic signs of strong nitrogen aggregation, evidence that points to long residence and heating in the mantle. The work also flagged a small set of very pure Type IIa stones, the kind with extremely low nitrogen.

Those traits reinforce why the site remains a natural classroom for mantle geology. The crystals carry deep time records in their lattice defects and inclusions.

Tips that match the science

Dry sifting works when the ground is firm, because it separates fine clay from dense pebbles where diamonds may hide. After rains, surface washing can reveal fresh material and change what sits on top.

“The minute I saw it in my shovel, I knew,” said Dewy White, a visitor from Paoli, Indiana. White followed a tip to dig near Canary Hill and stuck with a simple method.

What makes a find credible

Park teams see many lookalikes, including quartz and calcite that flash in bright sun. Diamonds at this site often show a greasy shine and rounded facet edges from weathering.

Verification checks hardness, weight, and telltale luster without cutting the stone. Those quick tests protect visitors from leaving a natural diamond behind by mistake.

A small crystal with a big backstory

A 2.71 carat rough diamond is round and pea sized, yet it reflects conditions set far below the crust. The crystal likely formed under high pressure, rose in lamproite magma, then sat in soil until a shovel lifted it.

That chain of events is why the field stays productive decades after earlier digs. The ground continues to weather, and seasonal plowing brings more material to the surface.