If we stop to think about it, diamonds have always been present in the history of humanity, whether to symbolize wealth, serve as currency, or be the main star of any piece of jewelry, especially engagement rings. These precious stones have always been made through mining, but scientists discovered how to grow them in a 100% sustainable way, and thus the sunlight-made diamond was born.

A new type of precious stone has emerged from the laboratories – the most valuable in history

Unlike common diamonds, sunlight-made diamonds do not require any type of mining; on the contrary, they are made in certified laboratories.

These laboratories reproduce the conditions of high pressure and temperature that occur naturally inside the Earth, and this effect triggers the crystallization of pure carbon, resulting in a real diamond.

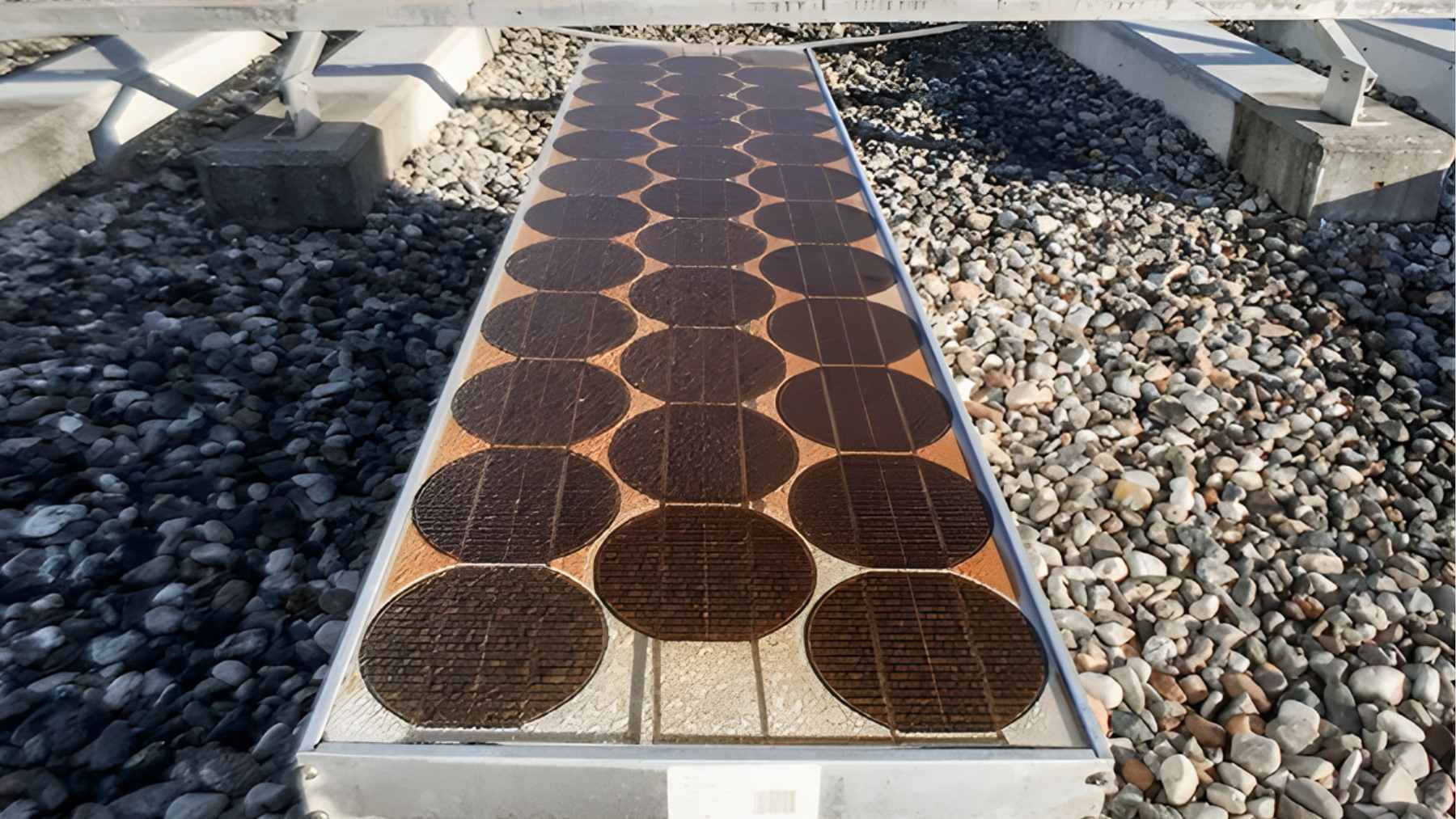

Not stopping there, sunlight-made diamonds use 100% renewable energy in their production. To be more specific, solar energy is used (it’s no wonder they’re called sunlight-made diamonds).

What makes a normal diamond different from a sunlight-made diamond?

If we just look at the appearance, it’s practically the same. A sunlight-made diamond has the same shine, the same hardness, the same composition, everything that we find in a natural diamond. In practice, no one would notice the difference just by looking at it.

What really changes between a regular diamond and a sunlight-made one is the creation process. One comes from mining, which is not only time-consuming but also very harmful to the environment. The other is created in a laboratory, in a much more controlled and clean way, and, for this very reason, it is gaining more and more popularity.

Nowadays, many people already take environmental impact into account when deciding what to buy, and that’s where the sunlight-made diamond stands out. It has a clear origin, a clean process, and everything can be traced. It’s a kind of luxury with a conscience.

If we go beyond the sustainable aspects, the sunlight-made diamond also stands out for its price, which can be four times lower than that of regular diamonds. They are also more exclusive, representing only 5% of lab-grown diamonds, yet they remain affordable, high-quality quality and very durable.

Why diamond mining should be rethought as soon as possible

When we talk about precious stones, it is worth remembering that diamond mining is expensive, and we are not just talking about money. Digging into the Earth for these stones disrupts entire ecosystems, wastes water, energy, and a host of other natural resources. Not to mention the complicated history of conflicts in some regions. It is a difficult process, in many ways.

In addition to all these factors, it is also worth mentioning that diamond mining requires a huge amount of natural resources, mainly energy and water, not to mention the carbon emissions involved in the entire process.

In a world that is trying to Solar panels will be mandatory for every home in this place as of 2027, continuing to extract diamonds from the Earth becomes contradictory and backward, it is no wonder that.

A new way to see the value in precious stones – because being sustainable is also a luxury

In addition to revolutionizing the precious stones market with its 100% sustainable production, the sunlight-made diamond has changed the way we see the value and preciousness of jewelry.

Before, 100% of a diamond’s value would be based on its rarity and difficulty in extraction. Now, what really matters is how much that precious stone positively impacts the environment. People will ask themselves whether that production is ethical, responsible and sustainable.

The sunlight-made diamond brings with it a change of vision, where the most beautiful and valuable things are also sustainable. And that is why this diamond has just become the most valuable in history.