A 25-year debate about some of the universe’s strongest magnetic fields may finally have a clearer answer. New computer simulations suggest that certain “low-intensity” magnetars can form their tangled, powerful magnetism through a pathway scientists long suspected but could not firmly test.

In a published study, the team argues that the messy aftermath of a supernova can spin up a newborn neutron star and kick-start a magnetic engine inside it. If that holds up, it helps explain a long-standing head-scratcher. How can some magnetars look “weak” on the outside, yet still erupt with dramatic X-ray flares?

A long-running mystery about “weaker” magnetars

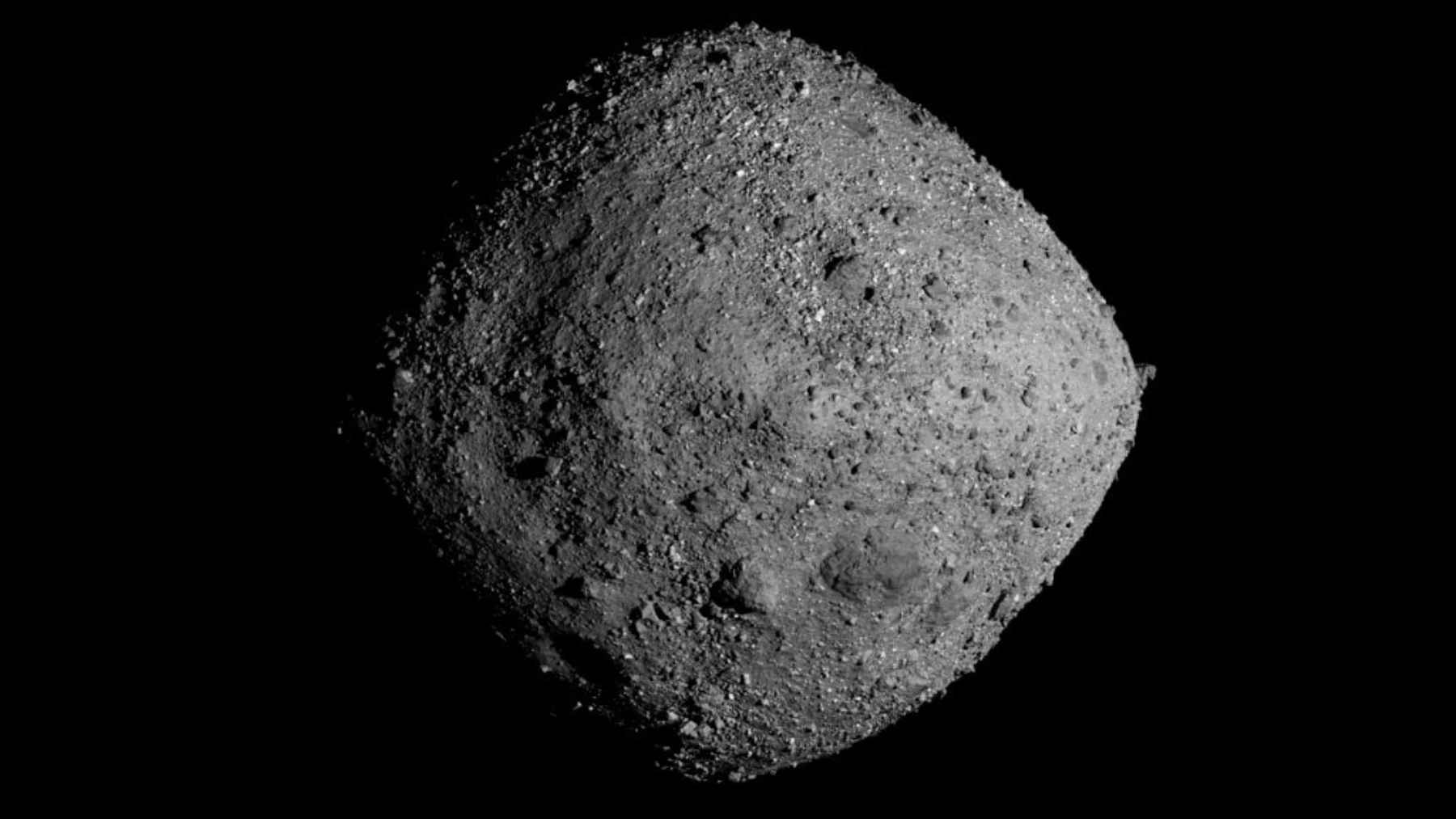

Magnetars are a rare type of neutron star, the ultra-dense core left behind after a massive star collapses. They are famous for magnetic fields so extreme they can be hundreds of trillions of times stronger than Earth’s, powering bursts of high-energy light.

But astronomers have also found “low-field” magnetars whose main, large-scale field seems far weaker than the classic picture. Despite that, they can still flare in similar ways, which has made researchers wonder whether the most important magnetism is sometimes hidden in smaller, knottier structures closer to the star’s surface.

The key idea, explained like you’re 15

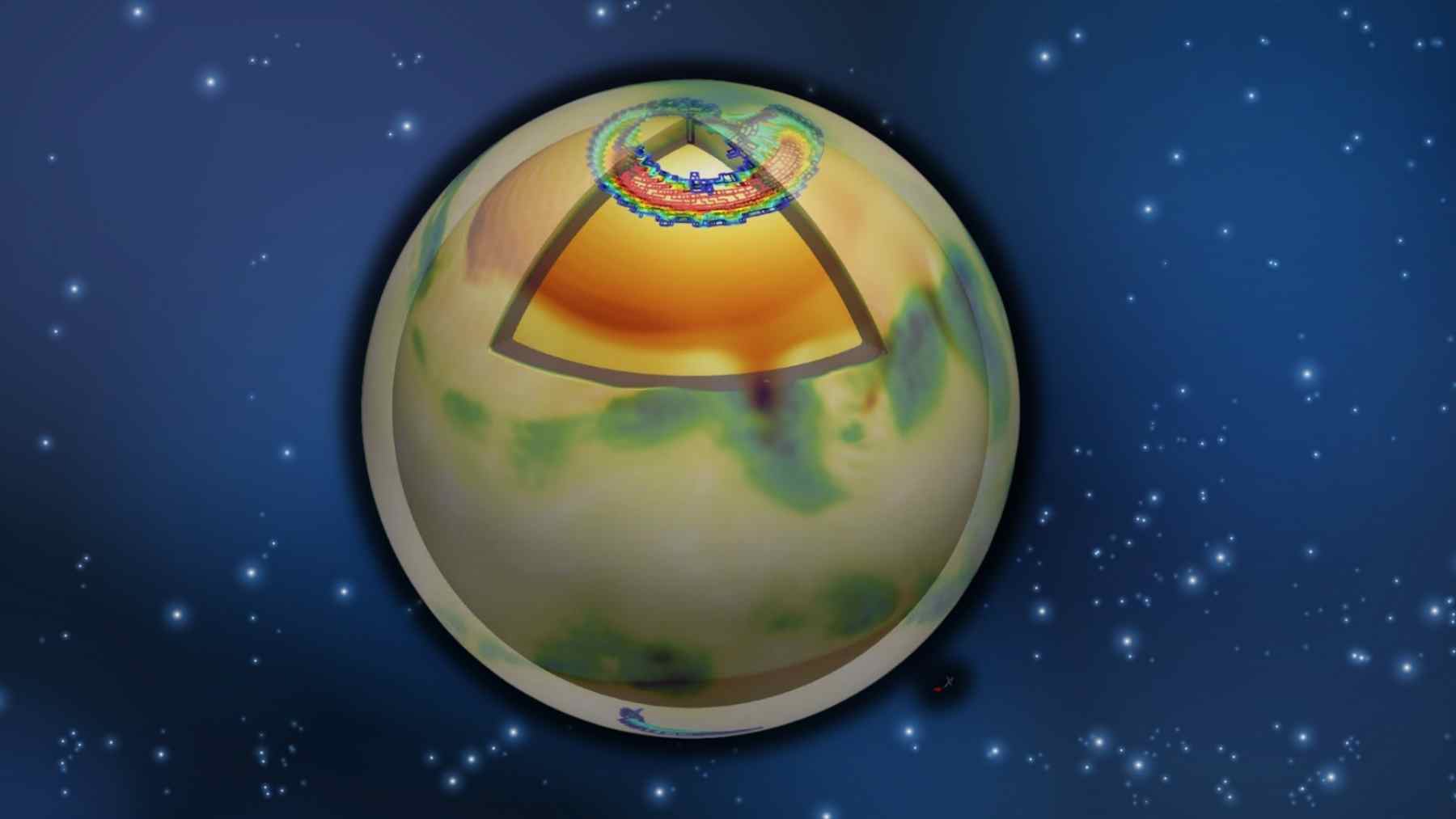

Think of a magnetar’s field like the magnetic pattern around a bar magnet, except the real story can be much more complicated. A telescope may mostly measure the big, simple part of that pattern, which is easier to detect from far away. The trouble is that a neutron star can also carry smaller, twistier magnetic “patches” that don’t show up as clearly in a single outside reading.

Why does that matter? Because those smaller fields can still stress the star’s crust, the solid outer layer, until it cracks or slips. When that happens, the star can release a sudden burst of energy that shows up as an X-ray flash, even if the big, tidy field looks unimpressive on paper.

How supernova “fallback” can rev up a newborn neutron star

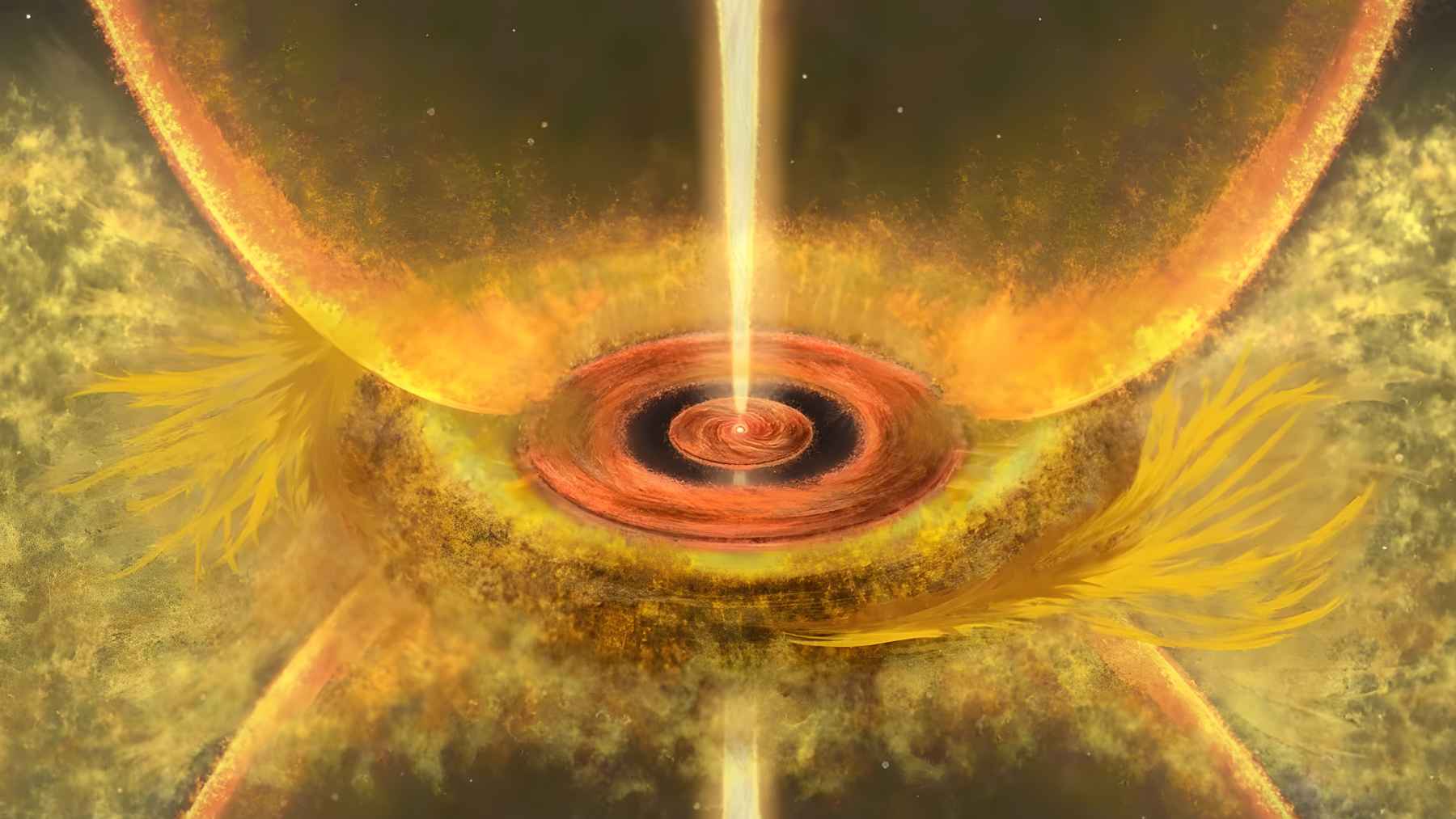

Right after a supernova, not all the blasted material escapes forever. Some of it can fall back toward the newborn neutron star, adding mass and, crucially, angular momentum that can make the star spin faster than expected.

That spin-up changes the conditions inside the hot, newborn object. In the new work, Dr. Andrei Igoshev, working with collaborators linked to Newcastle University and the University of Leeds, said the returning material can play “a very important role” in building magnetic fields through a specific internal process.

The Tayler-Spruit dynamo, without the math

The proposed engine is called the Tayler-Spruit dynamo, and the basic idea is surprisingly intuitive. If different layers inside a star rotate at different speeds, they can wind up magnetic fields the way you twist a rubber band, storing energy as the twist tightens.

Eventually, the wound-up field can become unstable and “kink,” creating new magnetic structure rather than simply snapping back. The concept traces back to an influential early-2000s paper by H. C. Spruit, but seeing it operate in realistic star-like conditions has been a slow, technical climb. (For more background, see the original work on “Dynamo action by differential rotation in a stably stratified stellar interior” published by Astronomy & Astrophysics.)

What the simulations add, and why observers care

The new simulations link that dynamo idea to the later life of the star, modeling how magnetic structure can evolve over long stretches of time after the explosive birth. The researchers report that the setup naturally produces low-field magnetars with weak large-scale fields but strong small-scale fields that can trigger crust failures and bursts.

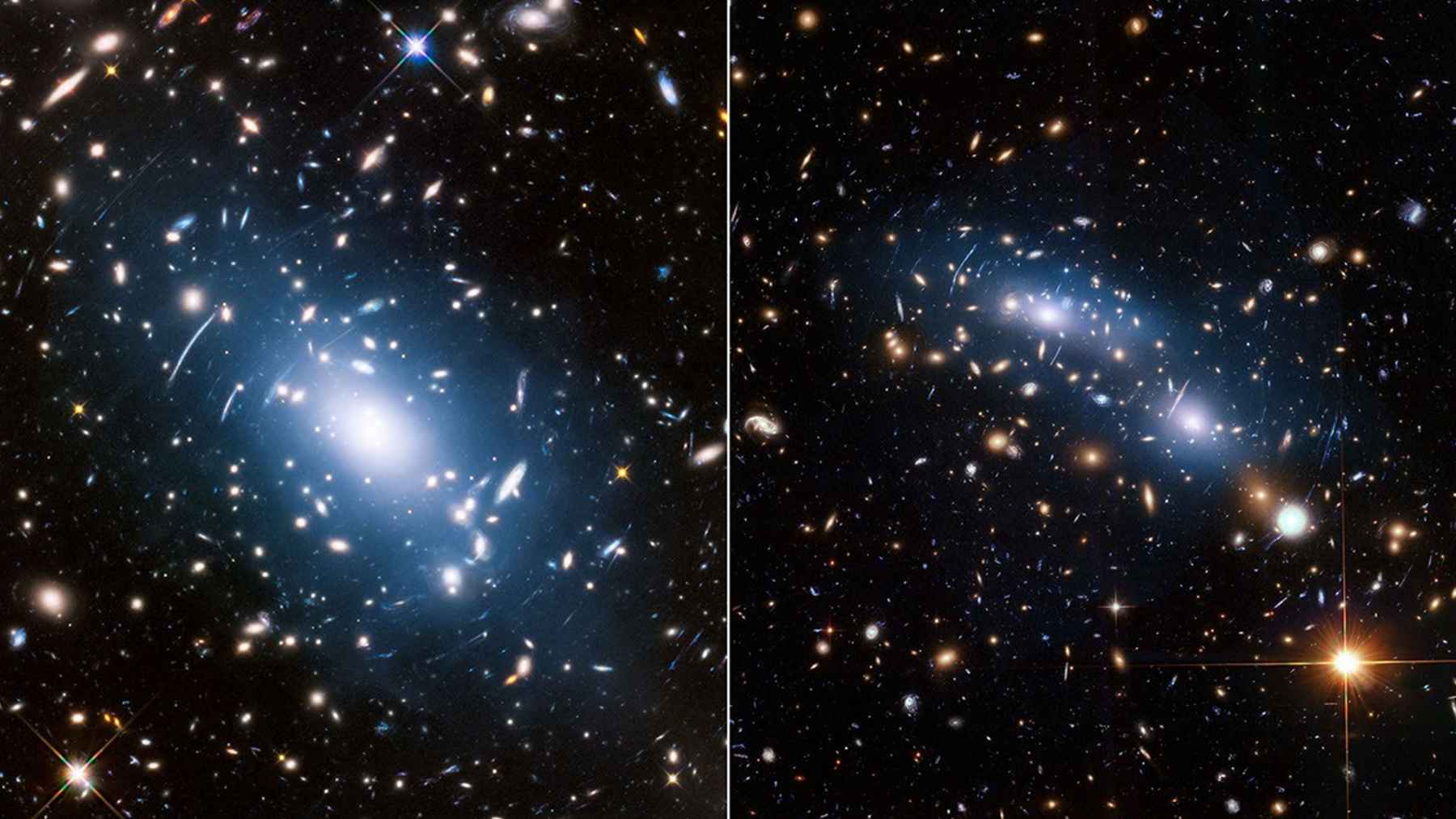

That’s a direct hit on what observers have been seeing in a few well-known cases. Earlier work has pointed to magnetar-like bursting from objects such as SGR 0418+5729 and Swift J1822.3-1606, even though their large-scale fields look modest compared to classic magnetars. (One example is the “A Low-Magnetic-Field Soft Gamma Repeater” report published by Science in 2010.)

Where this could lead next

In practical terms, this gives astronomers a more complete story to test. If the “fallback plus internal dynamo” route is right for at least some objects, it could help connect supernova leftovers, neutron star spin histories, and later flare behavior into a single chain of cause and effect.

It may even matter for bigger cosmic puzzles, since magnetars are often discussed as possible engines for unusually energetic explosions. Future observatories should be able to track magnetar hotspots and outbursts in more detail, helping scientists figure out when the “quiet-looking” stars are actually the ones hiding the sharpest teeth.

The main study has been published in Nature Astronomy and was published on Nature Astronomy.