The pill of the century: a single trip with LSD reduced anxiety for three months, according to a clinical study

What if relief from relentless worry did not mean another pill every morning, but one carefully supervised session that keeps helping for months. That…..

Goodbye to nuclear submarines: Australia signed a $368 billion deal with the United States to receive them, but a new congressional report makes it clear that they may never arrive

A new briefing for the US Congress has again raised the possibility that Australia may never receive the Virginia-class nuclear submarines at the heart…..

He created a lake to raise fish and installed cameras to monitor them, but ended up attracting eagles, deer, and owls to one of the continent’s most unexpected wildlife sanctuaries

Science

The pill of the century: a single trip with LSD reduced anxiety for three months, according to a clinical study

What if relief from relentless worry did not mean another pill every morning, but one…..

Chimpanzees apply medicinal plants to their wounds… and also help others

Deep in Uganda’s Budongo Forest, wild chimpanzees are doing something that looks uncannily familiar. When…..

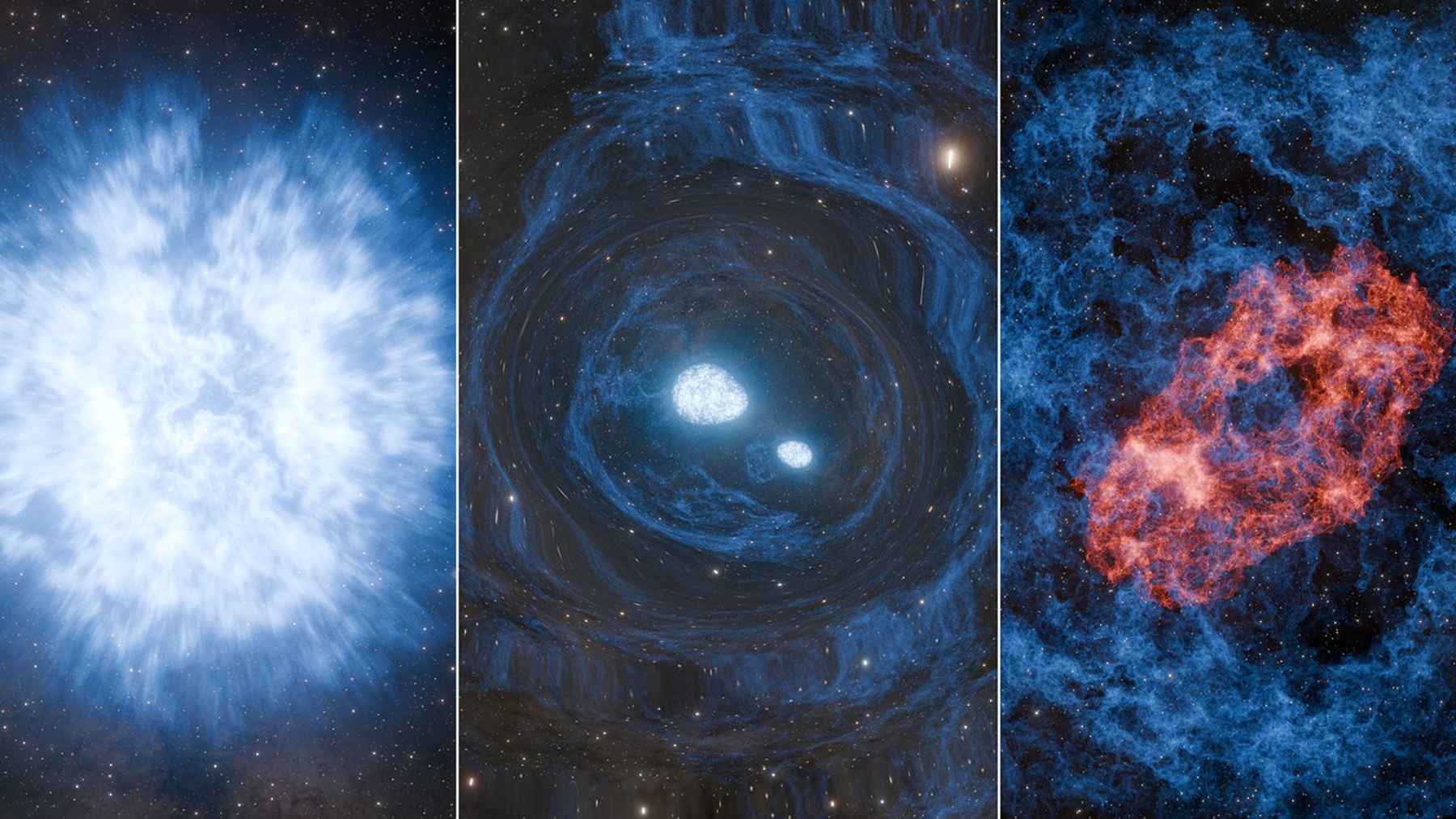

A star exploded, split in two, and then collided again within hours, leaving a double signature that has astronomers puzzled

That gold ring on your finger, the tiny metals inside your phone and even parts…..

Scientists discover that plants “scream” silently when they are stressed… and now even insects are beginning to hear them

If you grew up thinking plants are silent, think again. New research from Israel and…..

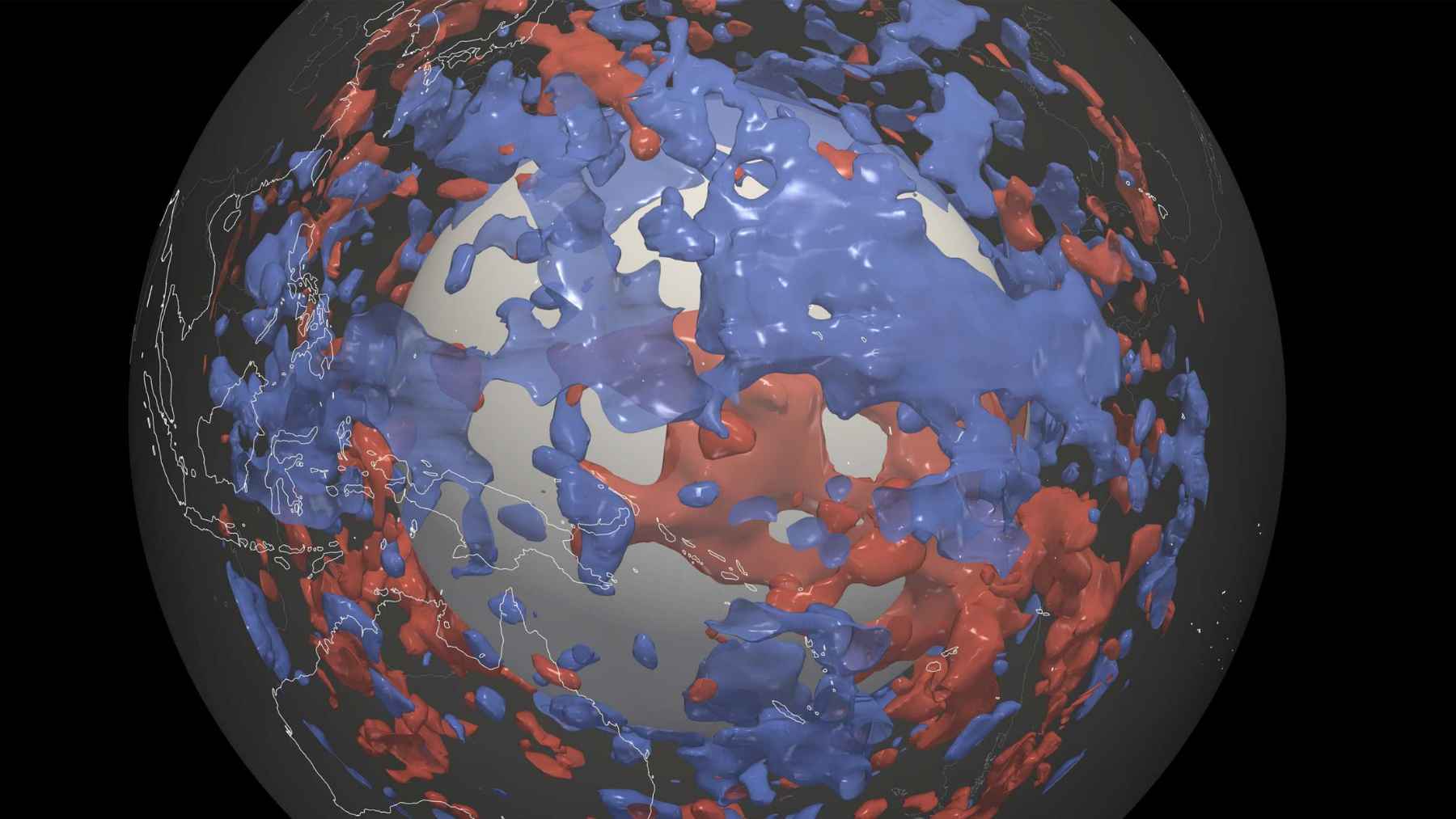

Something that “shouldn’t be there” appears beneath the Pacific, and a new high-resolution seismic model leaves geophysicists with a huge mystery

Deep below the Pacific Ocean, far beneath the seafloor and well out of reach of…..

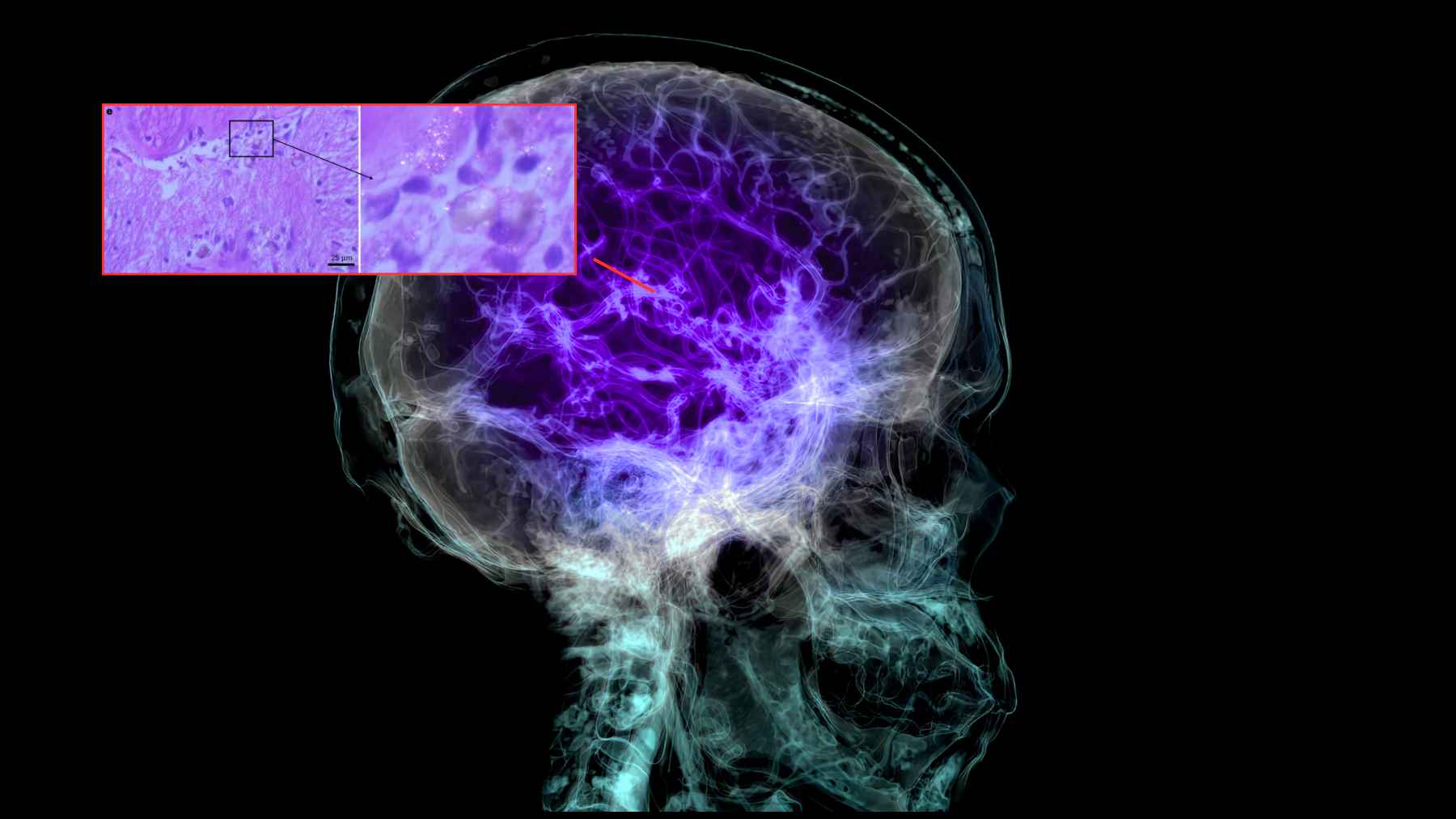

Your brain may be accumulating microplastics, and the big question is no longer whether they are there, but what they might be doing

You expect plastic in a water bottle or a grocery bag. You probably do not…..

The 75-ton Argentinosaurus could not run at all, and the study states that they were slow and heavy and barely exceeded 6 miles per hour

Picture a herd of massive dinosaurs or woolly mammoths thundering across the landscape at high…..

At first, you feel a brutal impact… but 12 hours later, something changes: this is what really happens to your body after showering with ice-cold water, according to science

From ice baths on social media to that last brutal twist of the shower handle…..

A 508-million-year-old worm from the primordial ocean, invisible teeth, and an embarrassing mistake: in 1977, they believed it walked on spikes… in 2015, they discovered that it wasn’t even its head

For decades, one of the strangest animals in the fossil record was drawn literally upside…..

What happens inside the body when older people sleep too little (or too much) and how that could hasten their death

Have you ever watched an older relative toss and turn at night and quietly wondered…..

Mobility

What many people install to protect their cars can now result in fines of $1,000 or even arrests

Drivers in California now face jail time and fines if they are caught with certain high-tech devices…..

The TSA has just introduced a surprise fee that no one expected: this is what you will have to pay if you do not have a Real ID or passport

Starting February 1, 2026, air travelers in the United States who show up at security without a…..

Thousands of illegally issued truck licenses in North Carolina could cost the state $50 million

A DMV error forces thousands of Californians to renew their identification just before important trips

Energy

Wind farms in trouble: Sweden supplies electricity “as much as the lines can carry.”

Economy

A renowned airline just accidentally discovered that it had a Boeing plane abandoned at an airport since 2012 and no one at the company had noticed for over a decade

We all misplace our keys or forget an old subscription. But an entire jetliner slipping…..

All U.S. Social Security numbers may need to be changed following a massive breach that is already being investigated as a national threat

Every American who has ever had a Social Security number may now be living with…..

Goodbye to loans for non-citizens: the 2026 measure that could change the landscape of entrepreneurship in the US (and it’s not the first time this has happened)

A rule change in Washington, D.C. is about to hit many of the people opening…..

Chinese geologists make history: they discover a deposit buried 3,000 meters underground with more gold than South Africa’s reserves, which could be worth more than a country’s total GDP

Deep under the hills of central China, geologists say they have located more than one…..

The U.S. government shuts down again and millions of people fear for their Social Security checks, but the agency responds with six words that bring immediate relief

Millions of Americans who rely on Social Security faced new worries as the federal government…..

Millions of people could face fines of up to $680 for failing to meet the most important tax deadline of the year, which expired on January 31

The most important IRS deadline for wage and contractor forms has already passed, and millions…..

Spain activates its largest naval plan since the Cold War: approximately $650 million, four high-tech submarines, and five F-110 frigates to address future threats.

In the middle of debates about energy bills and heatwaves, Spain has quietly launched its…..

If you have received this message, you may be entitled to receive up to $75 for each text message, and the deadline to file a claim is February 12, 2026

If your phone has ever buzzed again and again with marketing messages after you typed…..

A scientific “detective” from the United Kingdom has uncovered manipulated images in articles financed with public funds, and the United States is already recovering millions of dollars

A British biologist who spent his evenings scrutinizing cancer papers on a laptop has just…..

First he promised it with great fanfare, NOW he says it wasn’t him: Trump forgets his own plan to send $2,000 checks directly, leaving millions of people waiting

Americans hearing about $2,000 “tariff dividend” checks could be forgiven for feeling whiplash. In November…..

Technology

Goodbye to nuclear submarines: Australia signed a $368 billion deal with the United States to receive them, but a new congressional report makes it clear that they may never arrive

This little-known trick turns old television sockets into an ultra-fast cable Internet connection without the need for construction work or technicians

Elon Musk reveals his most ambitious (and detailed) plan for Mars: 1,000 spacecraft, 20 years of launches, and a self-sustaining city of one million inhabitants on Mars by 2050

A Chinese invention is revolutionizing the food industry: genetically modified mushrooms that taste like meat and use 70% less land than traditional livestock farming

A French nuclear giant advances northward: the aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle leads a military exercise involving drones, artificial intelligence, and electronic warfare unprecedented in Europe

Environment

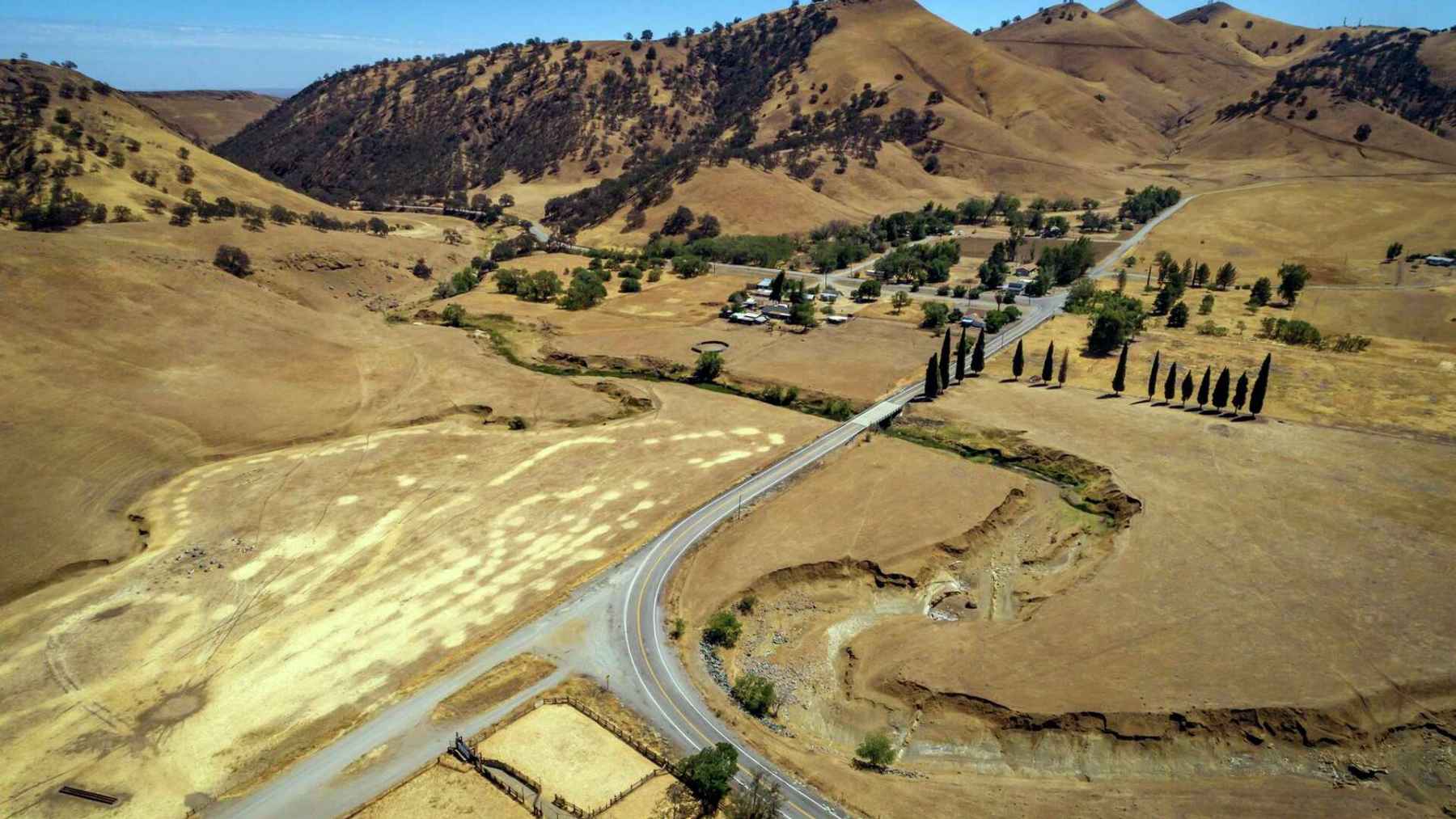

He created a lake to raise fish and installed cameras to monitor them, but ended up attracting eagles, deer, and owls to one of the continent’s most unexpected wildlife sanctuaries

It was supposed to be a straightforward farm project. Dig a five-acre lake, raise tiger…..

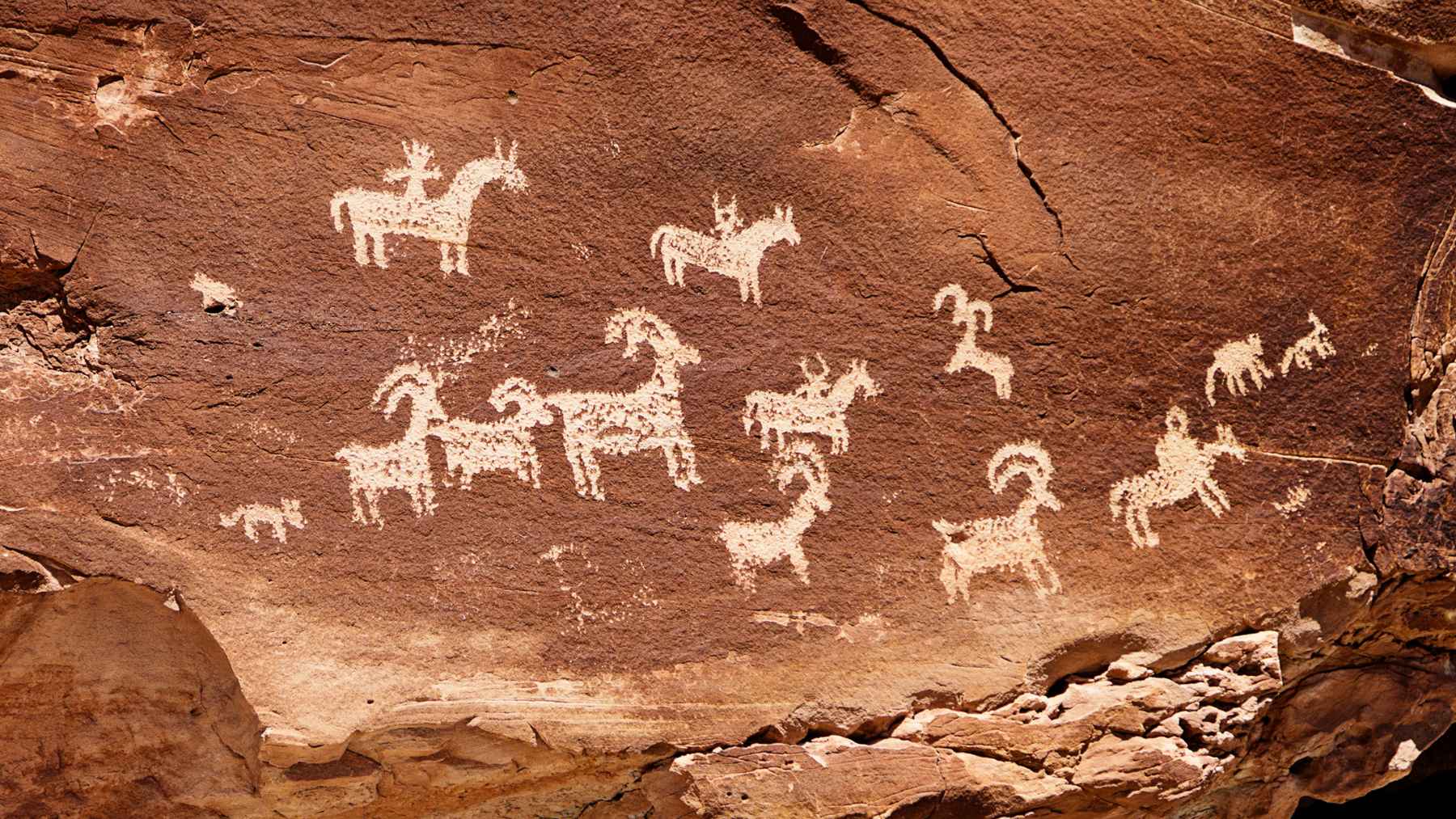

In 1940, a boy chased his dog through a hole in a tree and ended up finding a secret cave with more than 600 human paintings dating back 17,000 years that no one had ever seen before

In 1940, an eighteen year old and his dog squeezed into a hole beneath a…..

For the first time in global legal history, a country has recognized the legal rights of insects, and it is the stingless bees of the Peruvian Amazon that are taking the first step toward a new model of coexistence between nature and the law

In a remote corner of the Amazon rainforest, a tiny pollinator has just gained something…..

Alert in the forests: the unusual US plan to release 2,000 mice with paracetamol to curb a deadly plague

Picture 2,000 dead rodents, each carrying a small tablet of paracetamol, drifting into tropical treetops…..

2025 is expected to be the second or third hottest year on record, warns the UN

If 2024 felt unbearably hot, brace yourself. 2025 is not giving the planet much of…..

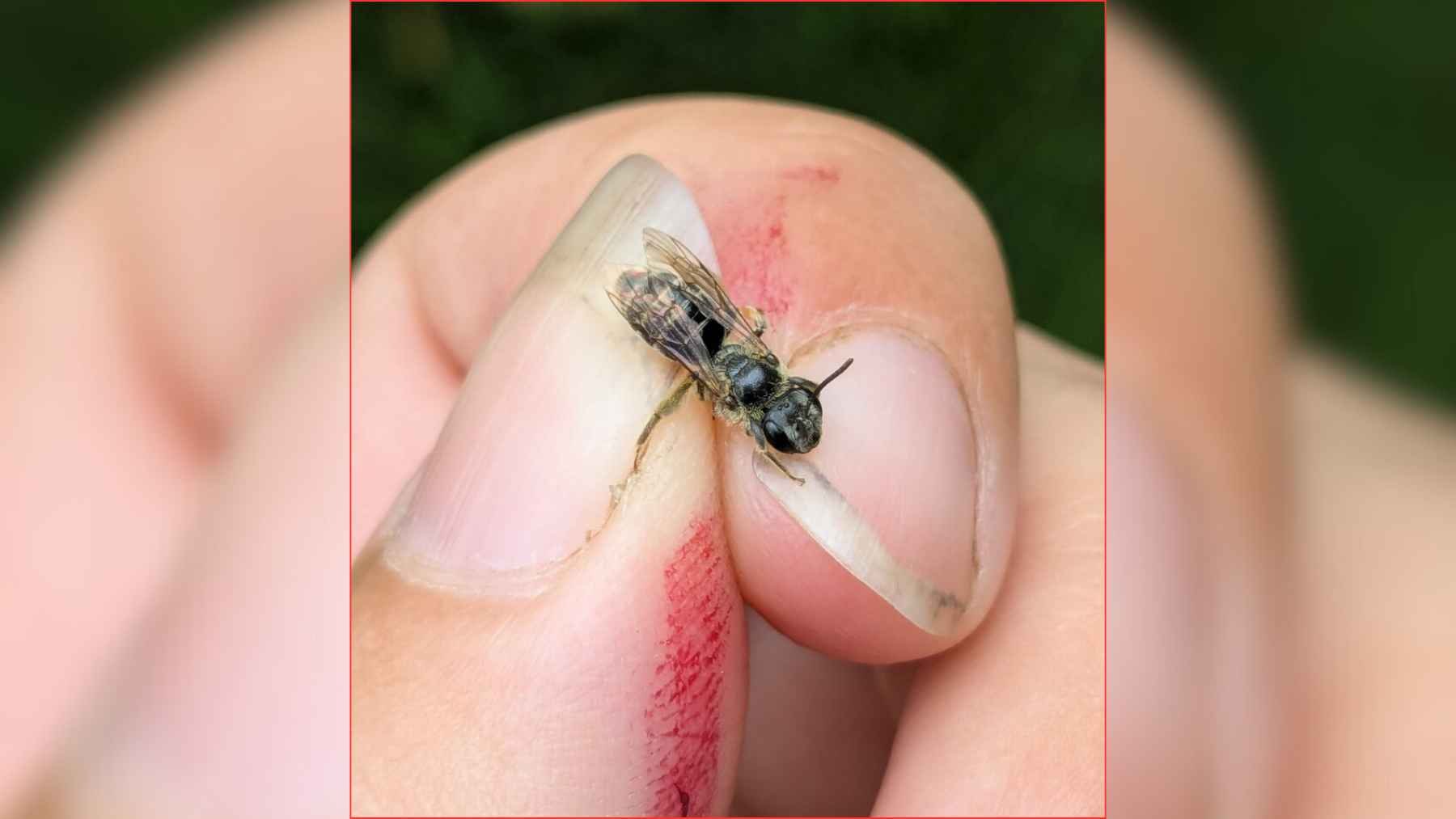

A biologist gets her fingers stained with berry juice… and accidentally discovers a species of bee that was believed to have been extinct in the region since 1904

Last summer, a scientist walking through a campus orchard in Syracuse noticed a small, plain…..

A giant tortoise, extinct for over a century, has reappeared alive after several failed expeditions, reviving a historic plan to save the species, a symbol of evolution

A giant tortoise that scientists once filed under “extinct for more than a century” has…..

Your continent could be feeding a volcano in the middle of the ocean… and you didn’t even know it

When a continent breaks apart, at the surface we see oceans that open very slowly……

Trending

Luxury or emergency: These VIP bunkers promise to save you from the apocalypse for up to $415,000, with bedrooms, showers, generators, and bomb-proof steel walls

For centuries, we believed that the moai statues were dragged until they destroyed the island… now science says that they walked, and history changes completely

A neighbor installs cameras in his garden in Dietlikon and films a red fox and a hedgehog sharing the same bowl of cat food in a garden while fireworks explode