Methane is out of control… but this strategy involving temporary CO2 capture could slow down its climate impact

Temporary carbon dioxide removals have been shown to neutralize methane’s intense but short-lived warming. By matching storage to methane’s brief climate pulse, the finding…..

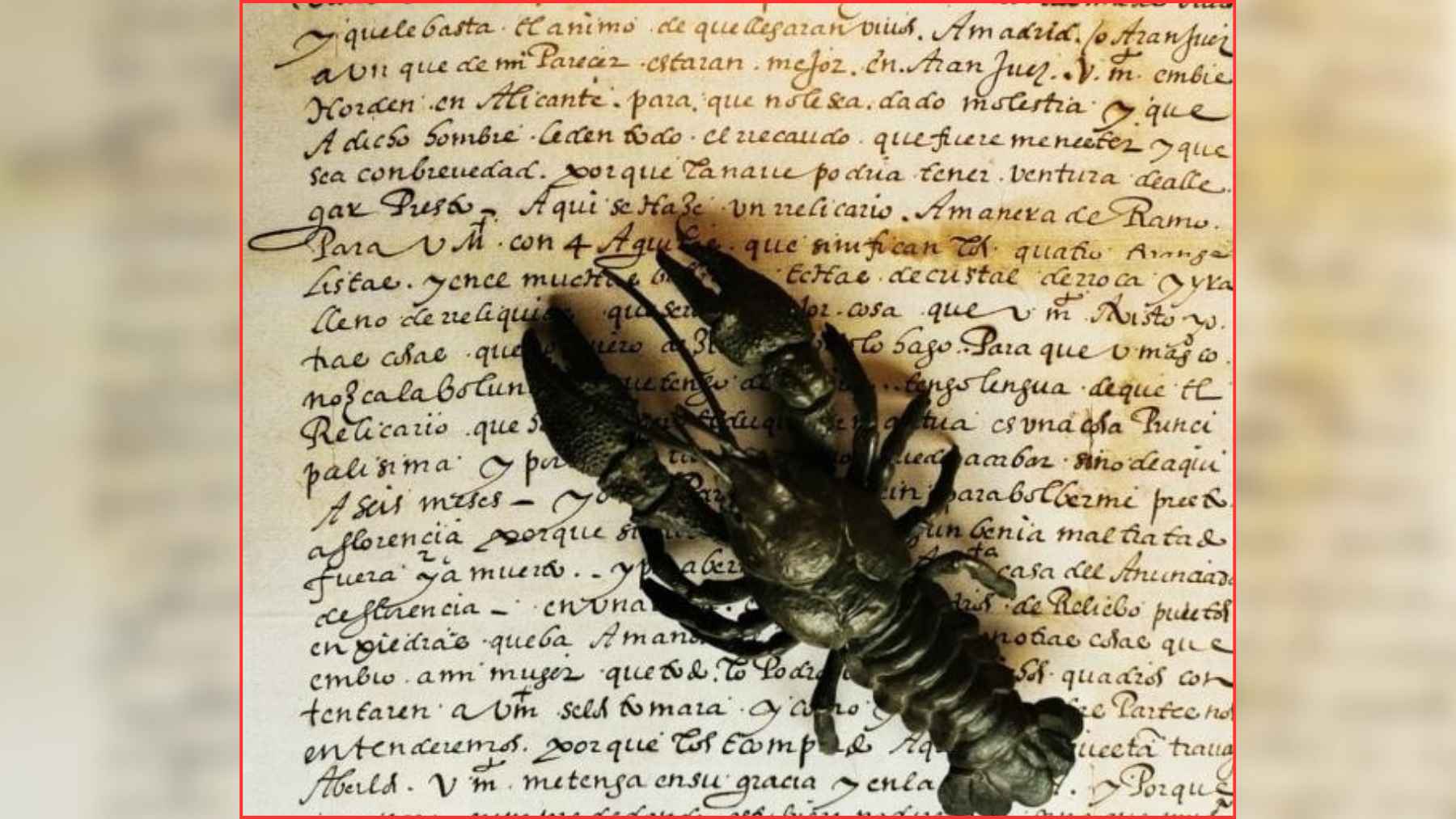

What for centuries was considered a native species could in fact be a “royal whim” from 1588, and now science is reopening the debate on the Iberian crab

For more than fifty years, the so-called Iberian crayfish has appeared in Spain’s official catalogs as a vulnerable native species that needs urgent protection……

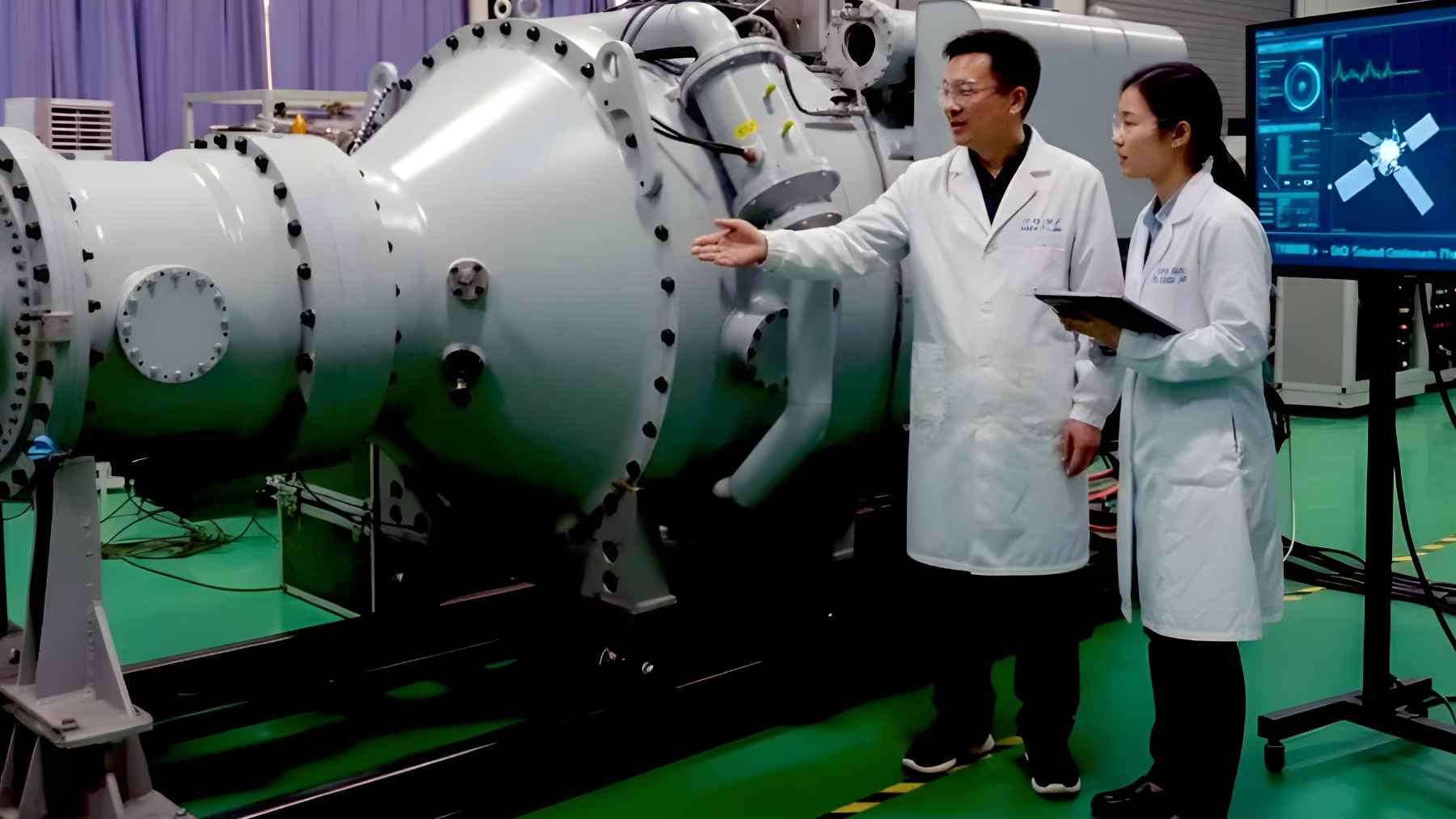

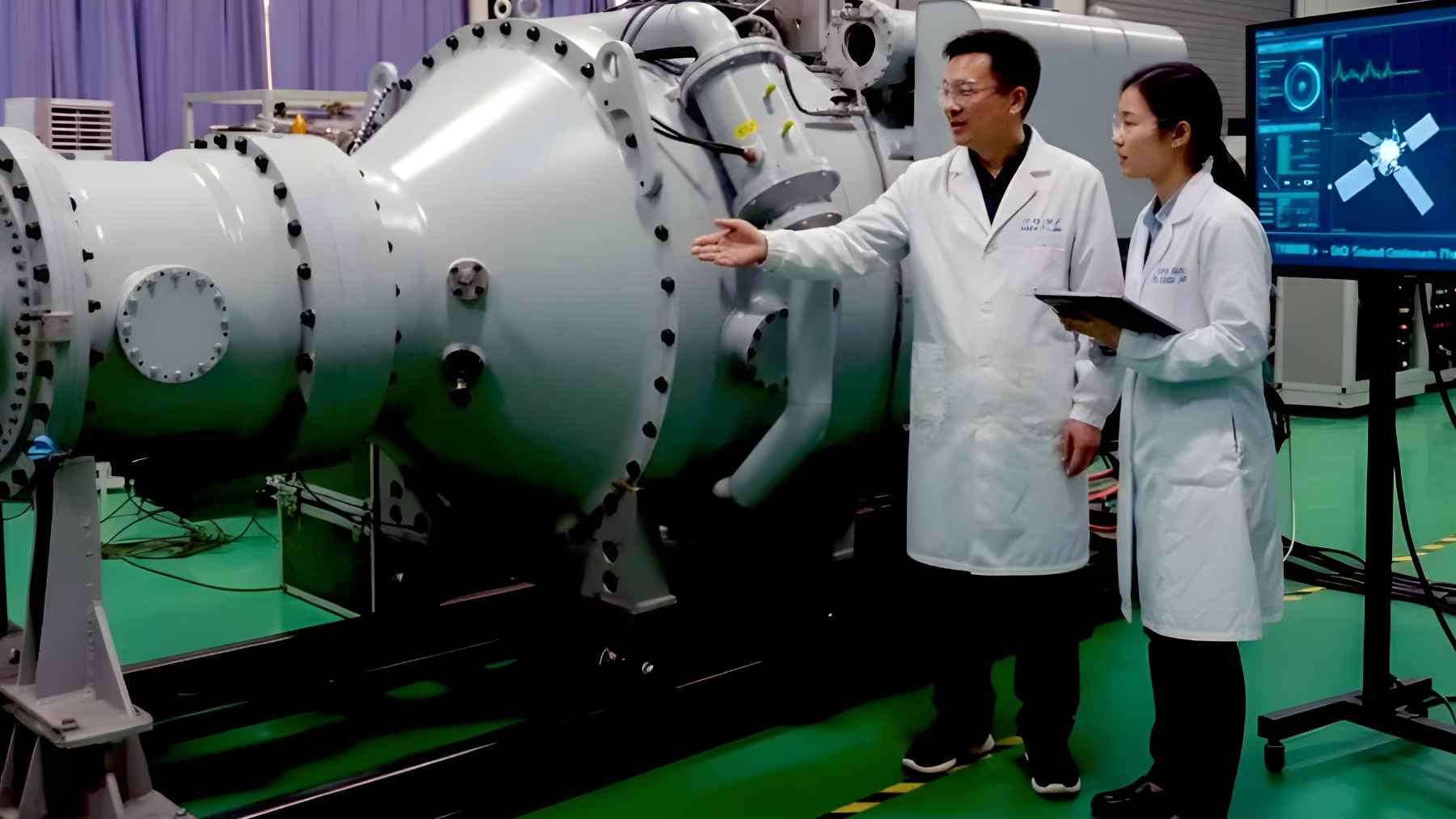

China claims to have created a 20-gigawatt microwave weapon capable of firing for 60 seconds, and the “phantom” target everyone is pointing to is Starlink

The colossal Helmantica dam, built in 1970, remains one of Spain’s largest hydroelectric power stations, with a wall as imposing as a medieval fortress

Millions of people could lose SNAP without realizing it, and the real change isn’t in soda or candy, but in a new rule that severely affects adults between the ages of 55 and 64

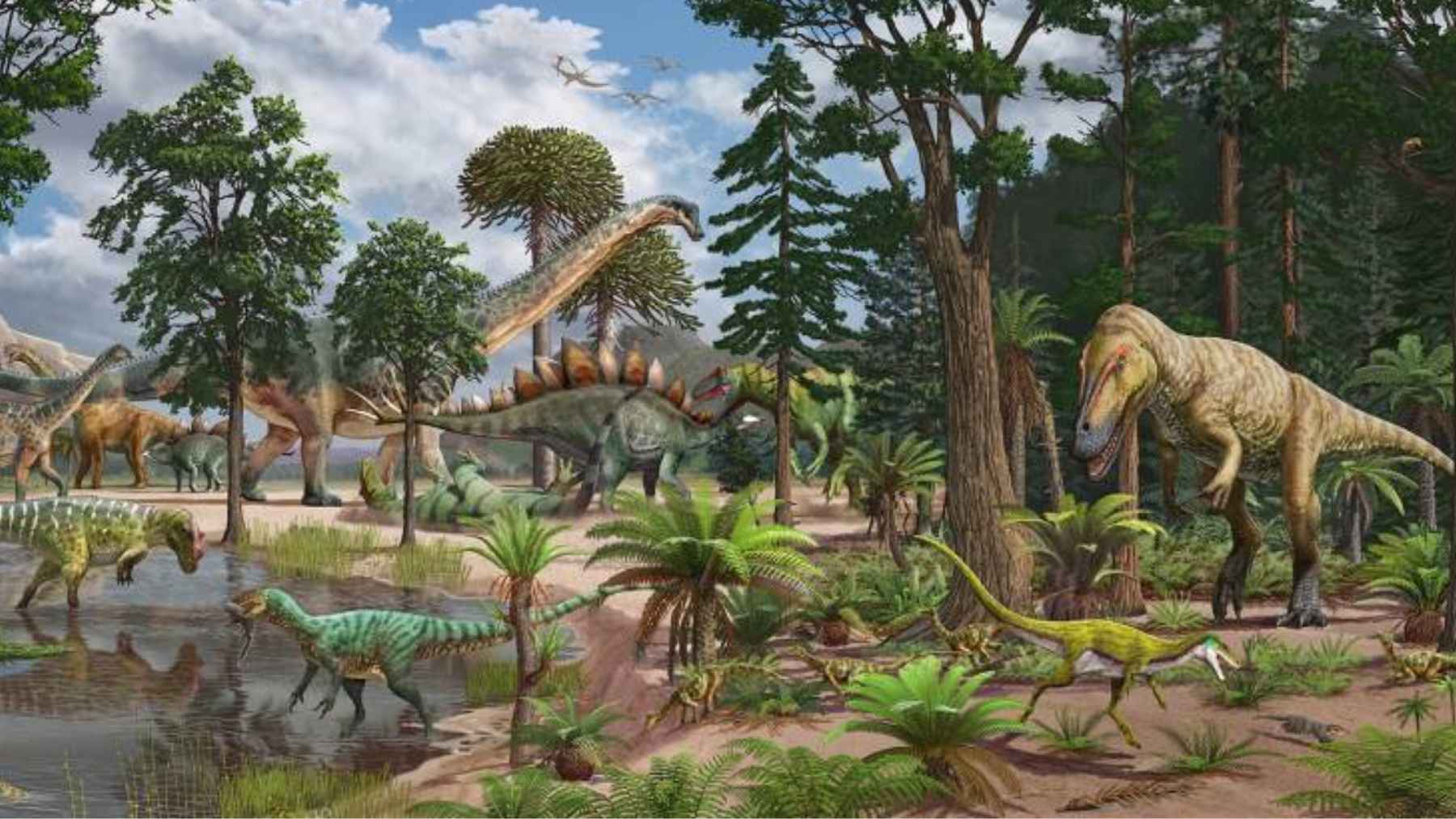

The giants of the past did not run as we thought, and science has just taken an unexpected turn in the classic image of mammoths and dinosaurs

Colorado scientists discover that cannabis could benefit memory and brain size in older people

Science

The giants of the past did not run as we thought, and science has just taken an unexpected turn in the classic image of mammoths and dinosaurs

Movies often show herds of mammoths and long-necked dinosaurs thundering across the landscape at full…..

No cockroaches or rats: this would be the last living thing to become extinct on Earth

When people joke about the end of the world, they usually picture cockroaches walking over…..

Caring for grandchildren not only strengthens family ties, but also improves memory and protects the brain, according to a study of nearly 3,000 grandparents

Looking after the grandkids may help keep an aging brain sharper, study finds. If you…..

A new study claims that we may be underestimating billions of people on the planet, and no one had noticed for more than 40 years

Humans like to think we know ourselves, including how many of us share this crowded…..

Colorado scientists discover that cannabis could benefit memory and brain size in older people

Forget the old joke about cannabis frying your brain. A large new study of more…..

Before collapsing, the observatory detected 100 signals that it suspected came from extraterrestrial beings

Have you ever imagined your old home computer quietly listening for aliens while you checked…..

They reconstruct the Jurassic ecosystem and discover that giant baby dinosaurs left to fend for themselves were the favorite prey of large predators.

Tiny, newly-hatched, long-necked dinosaurs may have been the main fuel that kept Jurassic predators going,…..

What they discovered in a bird could change what we know about redheads

If you have red hair or freckles in the family, you have probably heard that…..

In 2026, NASA breaks a long-standing rule and authorizes the use of smartphones on Artemis II, the first manned mission to the Moon since 1972, and the idea of seeing iPhones in orbit is already making headlines around the world

For the first time in NASA history, astronauts heading for the Moon will carry something…..

By studying the human brain, they discover the switch that activates its “navigation system”

Have you ever walked home on “autopilot” and barely remembered the route, then felt totally…..

Mobility

The A-10 Thunderbolt II, the aircraft designed around a 30 mm cannon with seven barrels and a complete system weighing over 4000 kg, because in close combat it continues to do what others dare not

What does a 30 millimeter cannon have to do with your electric bill or the next heatwave…..

Brazil is entering the final stretch of a historic milestone and promises to complete the first F-39 Gripen assembled in the country by the end of March 2026, a step that places it in the select club of supersonic fighter jet manufacturers

In late March, Brazil plans to roll out its first F-39 Gripen fighter fully assembled on home…..

Energy

Economy

Millions of people could lose SNAP without realizing it, and the real change isn’t in soda or candy, but in a new rule that severely affects adults between the ages of 55 and 64

Most readers hear about soda and candy first when SNAP comes up. But for many…..

Elon Musk admits in February 2026 that convincing married engineers to relocate to Starbase, 40 minutes from Brownsville and near the Mexican border, has become his biggest silent problem

During a recent interview, Elon Musk described SpaceX’s Starbase launch site complex in South Texas…..

From the gold that sparked the rush of the 1850s to antimony, which now accounts for 5% of the world’s supply: Victoria’s surprising new mining revolution

Gold put Victoria on the mining map. But the minerals driving today’s clean tech boom…..

Goodbye to the “normal” SSI payment in March: that’s why millions of beneficiaries believe their money has suddenly disappeared

Did your SSI payment seem to vanish this March? For nearly 7.5 million people who…..

Musk admits on X that production of the Cybercab robotaxi and Optimus humanoid is not taking off, and that could prove very costly

Musk did not simply promise new gadgets. He painted a vision of ultra-cheap robotaxis that…..

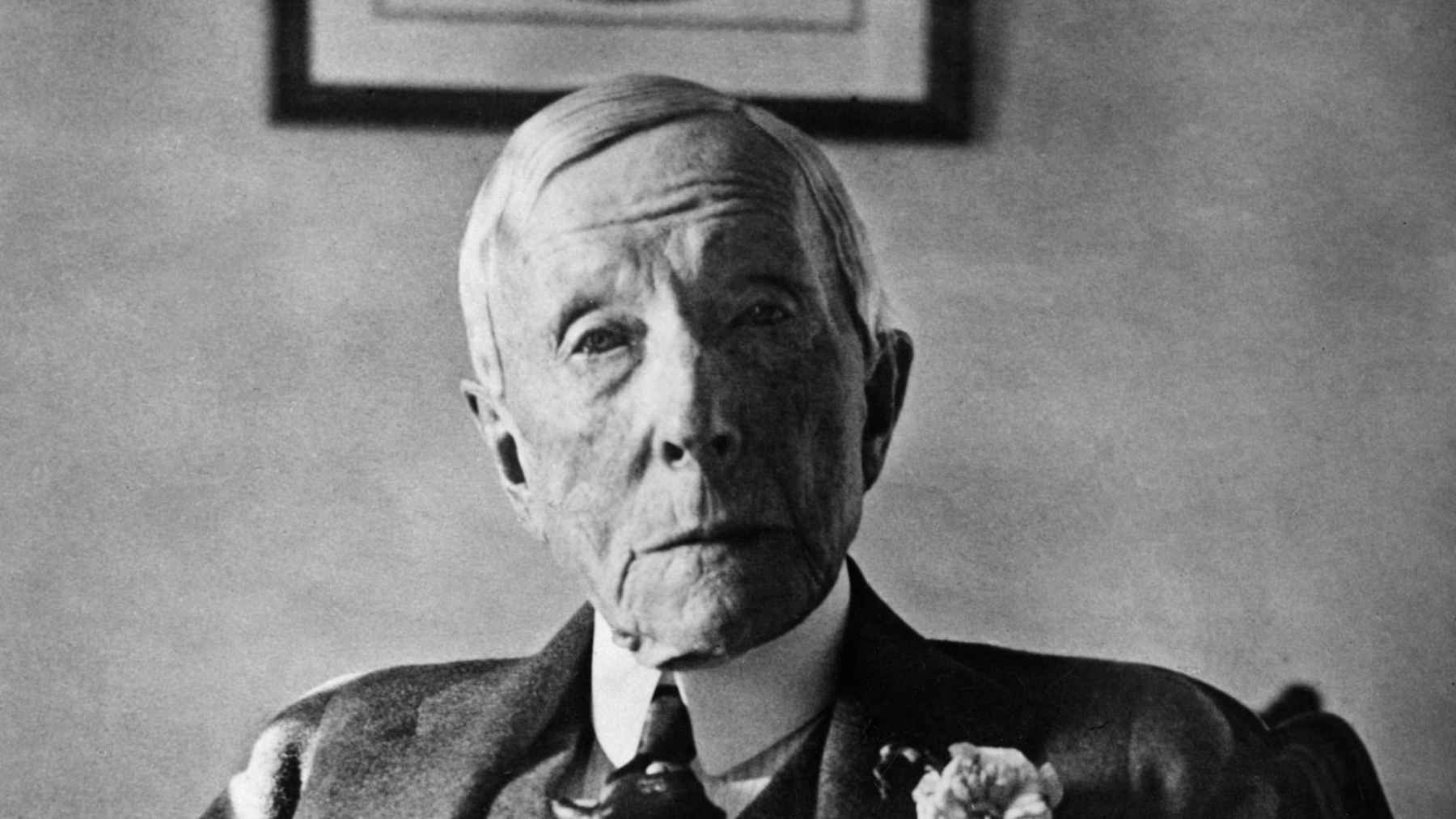

The disturbing quote from John D. Rockefeller that explains why you are never satisfied with what you have

More than a century ago, oil magnate John D. Rockefeller was asked how much money…..

A hidden deposit 2,000 meters underground could contain one of the largest gold reserves on the planet

Deep under the hills of central China, geologists say they have located more than one…..

What looked like an old farmhouse about to collapse concealed 2,200 retro computers stacked on the second floor… The lot weighed 22 tons and sold on eBay in a matter of days

For more than two decades, over 2,200 unused NABU personal computers sat stacked in an…..

Japan has just lowered its drill to 19,685 feet below the ocean with the Chikyu, and the message to China is clear: we are going after rare earths even if they are 1,180 miles from Tokyo

Far out in the Pacific, near the tiny coral atoll of Minamitorishima Island about 1,900…..

China has just found a 1,444-ton gold “monster” valued at more than $150 billion, and the strangest thing is that they say it is the largest find since 1949

China has confirmed the largest gold discovery in its modern history in the northeastern province…..

Technology

China claims to have created a 20-gigawatt microwave weapon capable of firing for 60 seconds, and the “phantom” target everyone is pointing to is Starlink

Russia tests a white suit with black spots nicknamed “penguin” in Ukraine, and within hours at least two soldiers are located and neutralized by FPV drones in the middle of a snowy landscape

A European country is already analyzing the brain waves of its fighter pilots, with the aim of ensuring that they do not let their guard down for a single second

Environment

Methane is out of control… but this strategy involving temporary CO2 capture could slow down its climate impact

Temporary carbon dioxide removals have been shown to neutralize methane’s intense but short-lived warming. By…..

What for centuries was considered a native species could in fact be a “royal whim” from 1588, and now science is reopening the debate on the Iberian crab

For more than fifty years, the so-called Iberian crayfish has appeared in Spain’s official catalogs…..

More than 68 stranded oil tankers increase the risk of oil spills in the Strait of Hormuz

More than 68 loaded oil tankers are sitting nearly motionless near the Strait of Hormuz,…..

Farewell to a century-old legend: Gramma, the Galapagos tortoise at San Diego Zoo, has died at the age of 141

Gramma, a Galápagos giant tortoise, has died at an estimated age of 141, according to…..

The “secret” garden of Angkor that has already attracted 600,000 visitors in just three years (and almost no one talks about it)

Less than three years after its official opening, the Angkor Botanical Garden inside the Angkor…..

Beneath an ice sheet averaging 1.2 miles thick and peaking at 3.1 miles, Antarctica concealed mountains, valleys, and giant rivers, and in 2026 we finally had the most detailed map to predict how much sea levels would rise

Hidden beneath more than two kilometers of ice, Antarctica conceals a rugged world of mountains,…..

The invasive Chinese crab adapts to almost any environment, feeds on invertebrates, fry, and even protected species, and competes with local fauna as if the river were its own

Walk along a quiet canal or past a city bridge and the water can look…..

Australia is culling thousands of donkeys so that dogs can save farms and water

In the remote interior of Australia, helicopters still fly low over red soil, shooting at…..

Trending

They had a robot watch hundreds of hours of YouTube videos, and it ended up learning to talk and sing without anyone programming it

She takes his dog to the vet to have a tooth removed, and what he does when he wakes up from the anesthesia has racked up 7.2 million views

The 7 best frozen chicken bags from the supermarket in 2026: crispy, with up to 16 g of protein per serving, and ready in less than 10 minutes

The vinegar trick for lentils recommended by nutritionists that changes the flavor and iron content more than you think

Not the kettle or the toaster: the appliance that suffers most during a storm, and technicians say you must unplug it without fail