In recent years, the evolution of renewable energy has been marked mainly by the installation of solar panels on rooftops, and Italy is also developing solutions. Homes, businesses, and even school buses have been looking for ways to generate clean energy and reduce costs. But the question arises: are we stuck with an outdated idea of where and how to capture this energy? That’s what Italian experts thought at Milan Design Week 2024 when they presented a new way to generate solar energy: through an origami-like cell.

The challenge of solar energy in large cities

To better understand this invention, we need to look at large cities, where installing solar panels on rooftops faces several challenges. This is because many residents live in apartments without access to the top of the building or in temporary constructions that cannot withstand certain interventions on the permanent structures. In addition, traditional solar panels themselves have been wasting around 66% of the incident light by reflecting this energy, without using it.

In other words, we have a very clear challenge with these traditional solar panels: how can we make it possible for residents of urban centers to also benefit from solar energy, without having to rely on a roof or major construction work? The answer may lie in glass facades… we know that this could be a huge turnaround, since they are often seen as the villains of energy consumption, due to excessive heat input and thermal loss. However, let’s think about it: what if these surfaces could be transformed into sources of energy and comfort?

The origami-like cell that will revolutionize solar energy

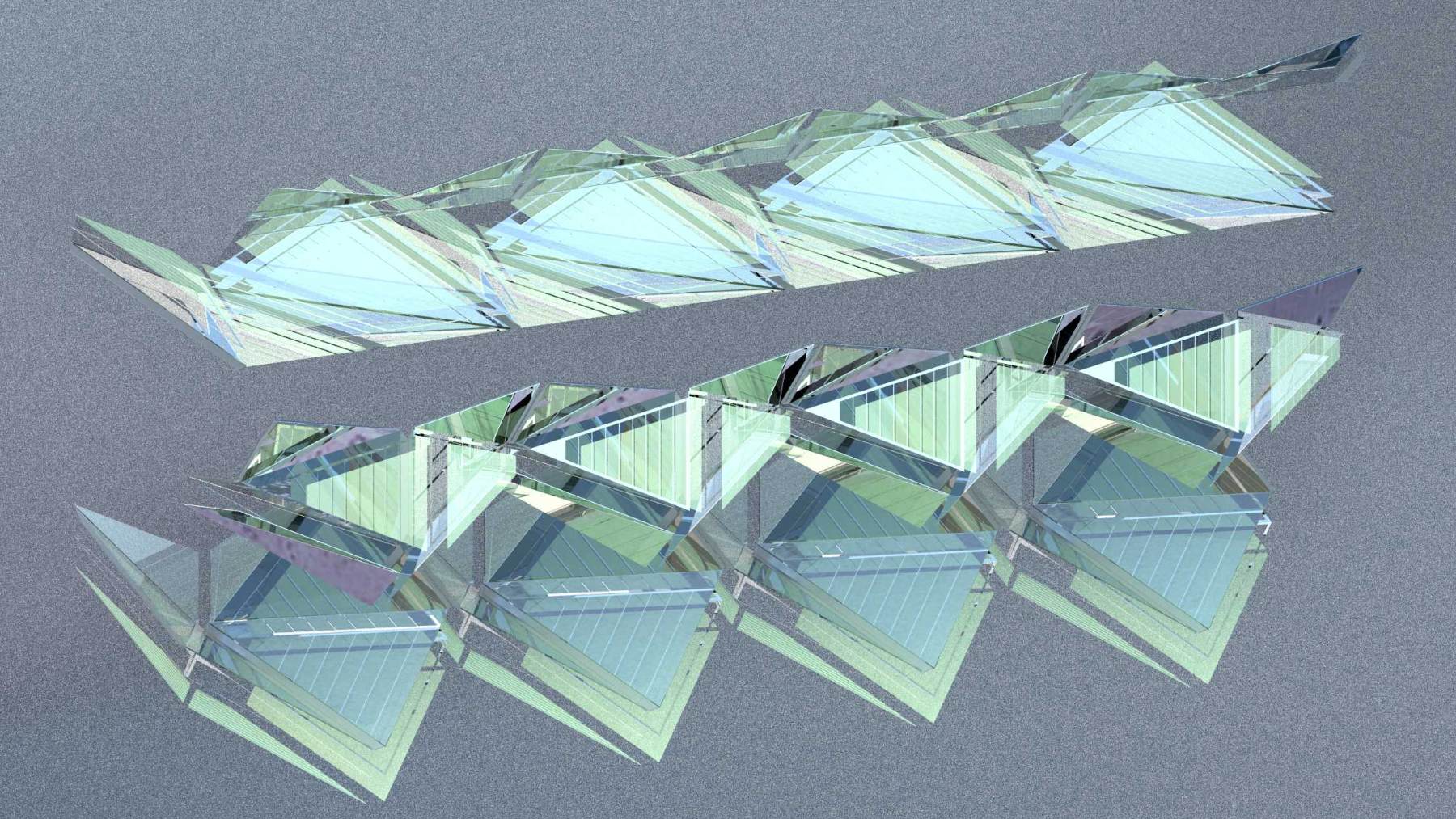

It was with this in mind that this origami-like cell, called Solgami, came onto the scene. Now, to tell you more about it: it is an origami-inspired curtain that generates solar energy and regulates the entry of light and heat into environments (like this other invention that generates energy through windows). This invention was developed by architect Ben Berwick and his studio, Prevalent. They created it with urban environments in mind, and also presented themselves as a hybrid between product and architecture.

In the original version of Solgami, it would function as a blind, made of transparent polymer printed with thin-film origami-like cells and reflective conductive inks. And then, when it was folded into an accordion shape, its structure would make light “bounce” between the panels, taking advantage of even part of the light that would normally be wasted.

Now, in the most recent version we have of Solgami, Solgami ALS is a little different. It was created as a retrofit system for windows, that is, it can be easily applied to interior surfaces, without tools and with simple installation. It’s incredible that, in addition to generating energy, it:

- Reduces internal temperature by up to 6°C.

- Reduces the need for air conditioning.

- Blocks reflections.

- And still maintains privacy.

And as if these benefits weren’t enough, this origami-like cell is made from 99% recycled materials, including plastics from water tanks and magnets from discarded electric vehicles.

Other benefits of origami-like cells

And if you think that the differences in this new product stop there, you’re wrong, because Solgami also redefines the experience with natural light. How so? Well, its screen can be adjusted to direct the lighting inside the room, meaning you can have a well-lit environment even without direct light.

Another difference is its customization, since the system can be calibrated considering the altitude and solar orientation of your window, optimizing the capture of light in each location. It is also worth mentioning that it is compatible with square and rectangular windows, and can even adapt to cases with door handles or structural details. Another invention that is completely adaptable and revolutionary is another origami cell that produces energy anywhere.