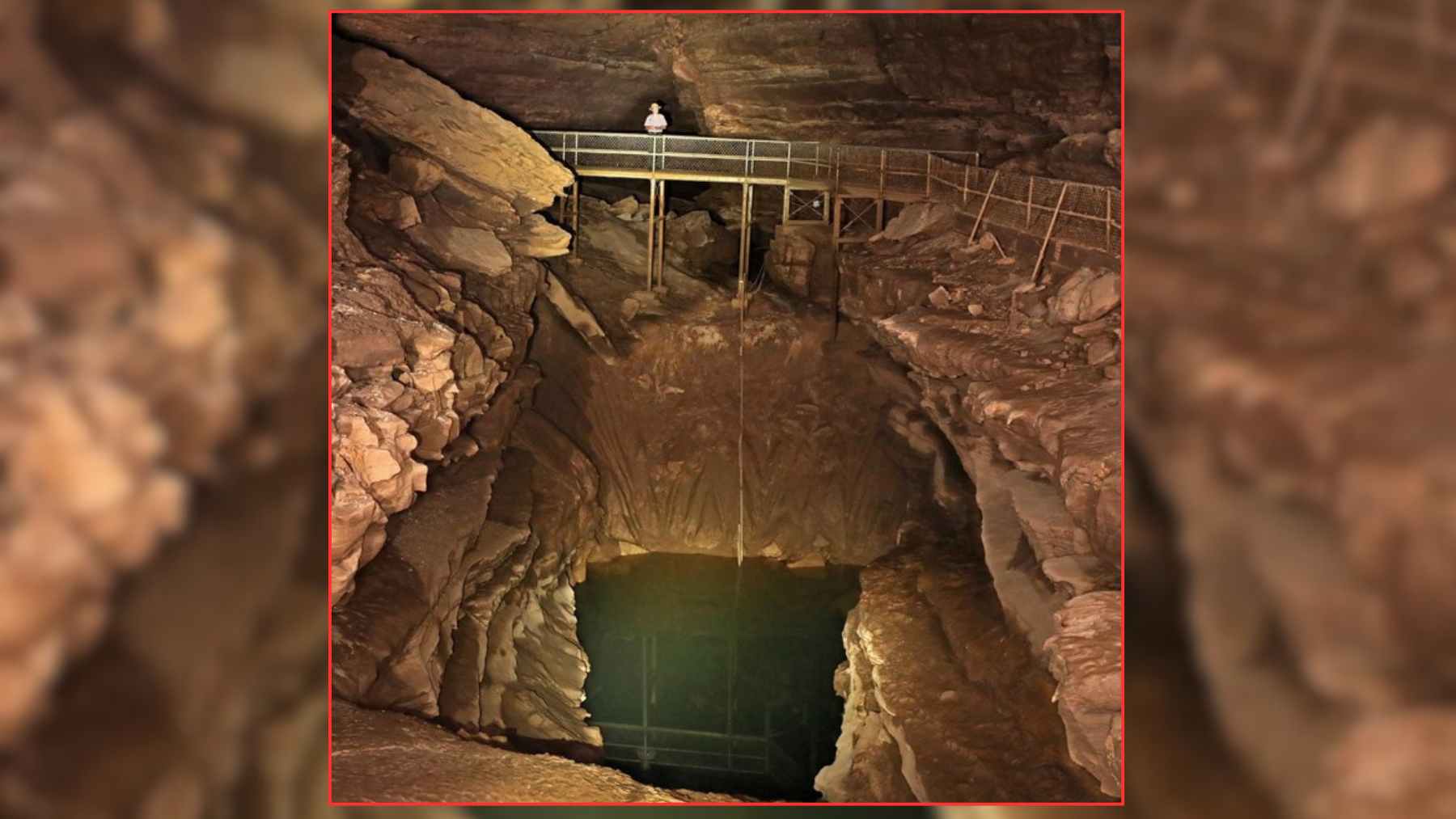

On the steep Mediterranean cliffs of Gibraltar, archaeologists have stepped into a room that no human had seen for tens of thousands of years. Hidden behind a plug of ancient sand in Vanguard Cave, part of the Gorham’s Cave Complex, a 13-meter chamber lay sealed for roughly 40,000 years, preserving rare clues to the final chapters of Neanderthal life on a changing coastline.

For scientists, this is not just a dramatic discovery. It is a time capsule that connects deep prehistory with very current questions about sea level rise, coastal ecosystems, and how humans respond when their environment transforms around them.

A Mediterranean time capsule

Gorham’s Cave Complex sits within the Gibraltar Nature Reserve and was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2016, largely because it preserves some of the last known refuges of Neanderthals in Europe. Vanguard Cave and its neighbors show evidence of Neanderthal use for roughly 100,000 years, possibly until around 28,000 years ago, later than many other sites across the continent.

When researchers from the Gibraltar National Museum dug into the sand at the rear of Vanguard Cave, they uncovered a high chamber whose floor held the bones of lynx, hyena, and griffon vulture, along with scratch marks left by carnivores.

Mixed in was something very different. The shell of a dog whelk, a sea snail that could not have climbed into the chamber on its own. That small shell strongly suggests that a Neanderthal carried coastal food into this hidden space, weaving marine resources into daily life even inside the rock.

What kind of coastline did they see when they walked out of that cave?

A drowned hunting ground

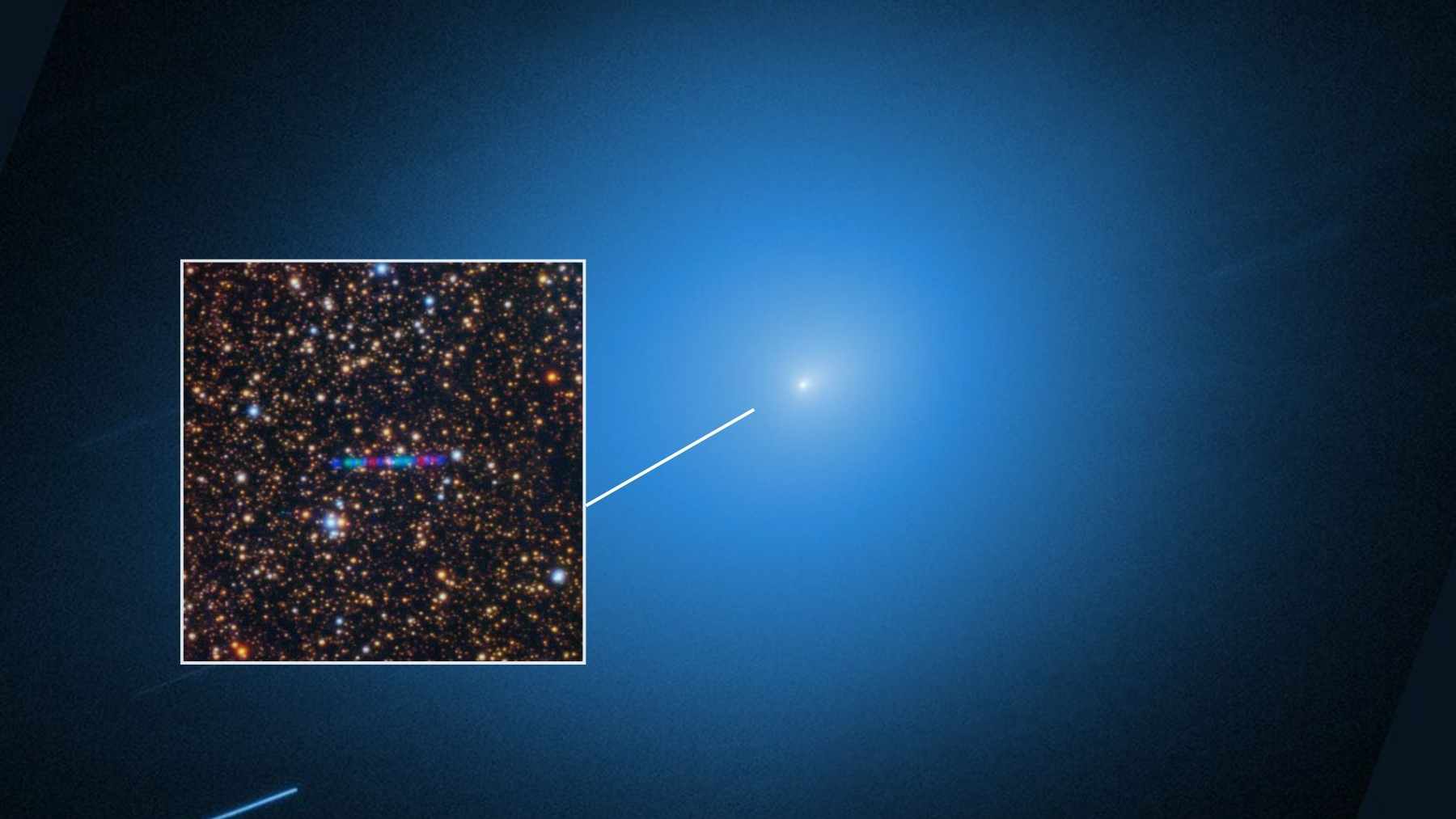

Today the cave mouth almost meets the waves, and visitors reach it through a protected marine and nature reserve. During the Ice Age, sea levels were much lower. Research on the Gorham’s Cave Complex shows that Neanderthals once looked out over an open shelf that stretched up to 4.5 kilometers from the caves, a landscape of sand dunes, patches of stone pine woodland, Mediterranean shrubs, seasonal lakes, and abundant wildlife. One team has described it as a kind of “Mediterranean Serengeti.”

That ancient plain is now underwater. The shift from wide coastal grasslands to a narrow cliff edge is a vivid example of long-term sea level rise reshaping habitats. It is hard not to see the parallel with modern coastal cities watching the tide lines creep higher year by year.

Seafood, fire, and intricate behavior

Excavations in Gorham’s and Vanguard Caves show that Neanderthals in Gibraltar were not simply chasing big land animals. Their trash layers are packed with mussel shells along with bones of fish, monk seals, and dolphins, clear evidence that they harvested marine life and brought it home to cook. Some of these remains bear cut marks from stone tools, which means dinner was carefully processed, not just scavenged.

On the cave floors, deep cross-hatched engravings cut into bedrock hint at symbolic behavior or simple artwork, adding another layer to the story of how these groups saw their world. Neanderthals here were coastal foragers, toolmakers, and perhaps artists, tightly linked to a shoreline ecosystem that supplied both food and raw materials.

A tar workshop in the dark

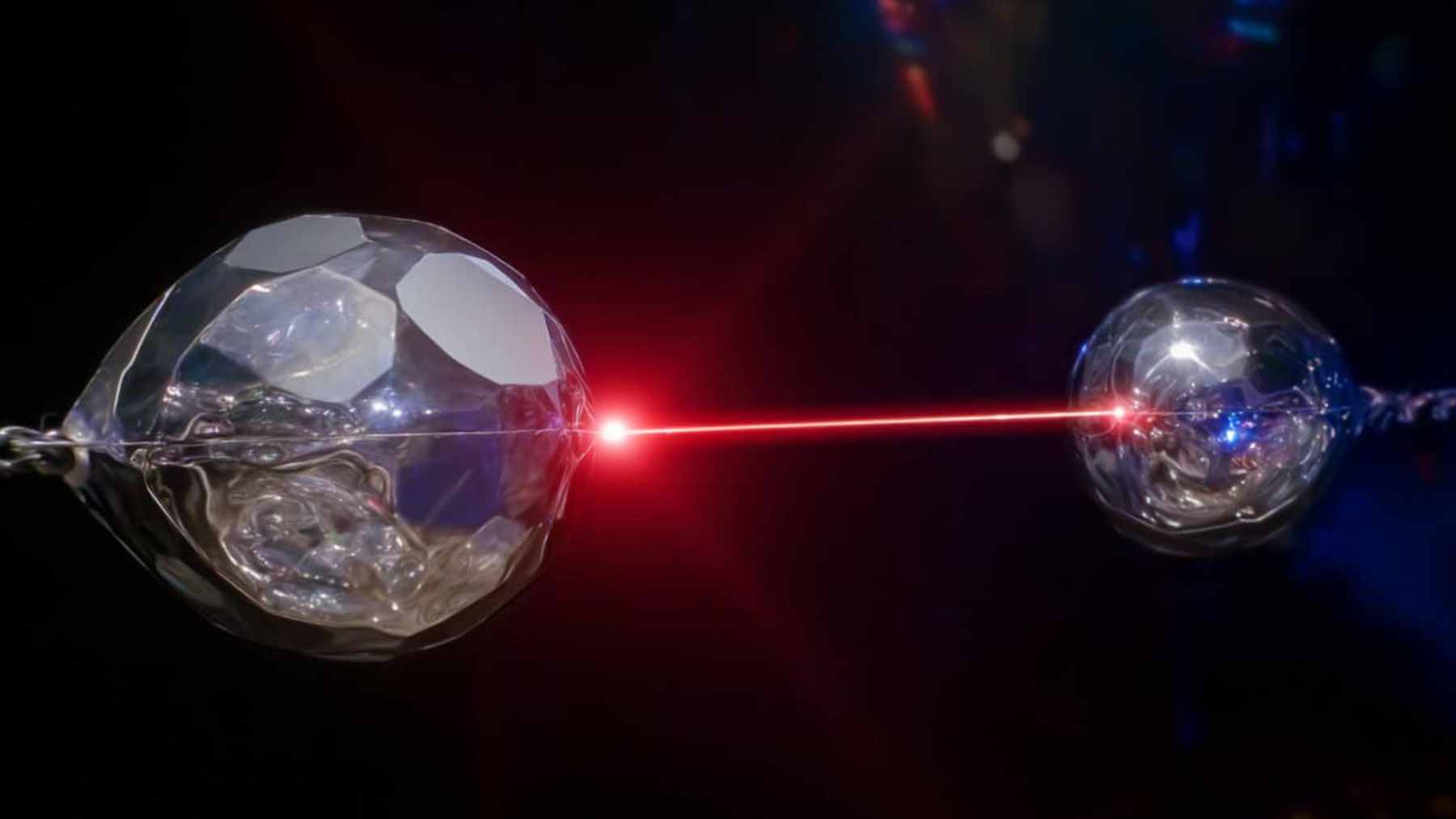

The environmental story deepens with one of the most striking recent findings from Vanguard Cave. In 2024, an international team described a pit-like hearth, around 60,000 years old, that Neanderthals used to make plant tar for glue.

Rather than simply burning birch bark in the open, the structure shows that they heated buried plant fragments without oxygen to draw out sticky resin. Analyses suggest they probably used gum rockrose, a shrub common in Mediterranean habitats, instead of birch, which would have been rare in this region. The tar helped them haft stone points onto wooden shafts, turning local rock and wood into reliable spears for ambush hunting on that now-drowned coastal plain.

The site only survived because a fast moving sand dune sealed it, along with pollen and spores that preserve a snapshot of the outside environment. In practical terms, a single hearth links plant ecology, animal behavior, and sophisticated technology in one small patch of cave sediment.

As Gibraltar’s Minister for Heritage John Cortes put it, “The Gorham’s Cave Complex continues to receive international recognition and this scientific study offers a fascinating insight into the cognitive development of Neanderthals.”

What this means for us

Most of us will never set foot inside Vanguard Cave. We feel environmental change in other ways, like higher electric bills from longer heat waves or shrinking beaches after winter storms. Yet the story unfolding under the Rock of Gibraltar quietly reminds us that coastal environments have always been dynamic, and that human relatives have faced rising seas before.

Neanderthals here responded by broadening their diets, mastering new materials, and using every part of a rich coastal ecosystem. That did not ultimately save their species. Even so, their ingenuity and their reliance on a productive shoreline underline how much is at stake as modern seas climb and marine food webs shift.

Protecting coastal reserves today is not only about birds, dolphins, or dunes. It is also about safeguarding the very settings where our wider human family once learned to survive.

The press release was published on the Gorham’s Cave Complex website.