What if the next big step in human technology is as small as an extra thumb on your hand? A new study shows that for most people, learning to use that extra digit takes about as long as brewing a cup of coffee.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge and collaborators tested a 3D printed “Third Thumb” robotic device on 596 visitors at the Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition in London. Participants ranged from toddlers to people in their nineties, yet almost all of them could strap on the device and start picking up objects within a minute.

The work, published in the journal Science Robotics, focuses on a simple but powerful question. Can wearable motor augmentation be designed so that it works for almost everyone, not just a narrow slice of the population who happen to match a lab’s “average user” template?

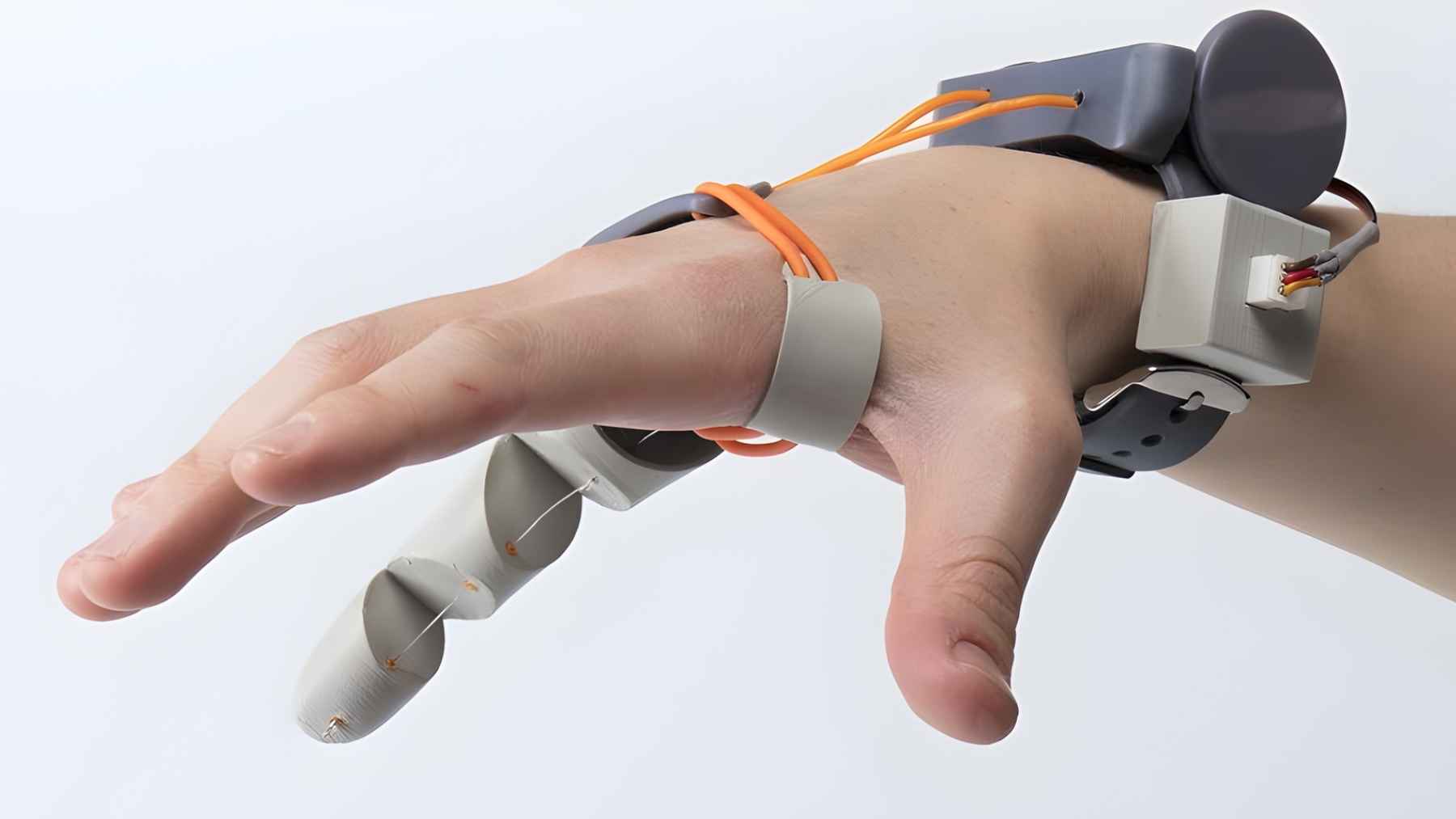

How the Third Thumb works

The Third Thumb sits on the side of the hand opposite the biological thumb and is printed in two sizes with flexible straps so it fits a wide range of hand shapes. It is powered and controlled with pressure sensors under the big toes. Pressing one toe moves the Thumb across the palm, pressing the other moves it toward the fingers, and easing off lets it glide back. The harder the user presses, the further it moves.

At the exhibition, visitors had up to one minute to get used to the device, then performed one of two tasks. In one, they used only the robotic thumb to pluck pegs from a block and drop them in a basket. In the other, they teamed the Thumb with their natural fingers to move soft foam shapes that demanded more dexterity.

Out of 596 people aged three to ninety six, only four could not use the Thumb because it did not fit securely or they were too light to trigger the foot sensors. That means 99.3% could wear and control the device. Of the remaining group, 98% managed to manipulate objects successfully in their very first minute of use, typically handling one item every few seconds.

Who learns fastest with an extra finger

The team found that many familiar dividing lines did not matter much. Performance was similar for women and men. Left-handed users did just as well as right-handed users, even though the Thumb was always mounted on the right hand. People who played instruments or had “handy” jobs and hobbies did not gain a strong advantage in this short trial.

Age told a more nuanced story. Young adults were the quickest group to adapt. Older adults in their thirties and beyond generally matched that performance, although within the oldest age bracket there was a gradual decline as age increased, likely reflecting normal changes in movement and cognition.

Younger children, especially those under eleven, struggled more. Six of the thirteen people who could not complete the task were below ten, and even older teenagers tended to lag behind young adults despite growing up with digital gadgets around them.

For the researchers, that gap raises fresh questions. Are children limited mainly by motor control, by attention, or simply by how instructions are explained? Would extra training erase the difference? Those answers will matter if augmented hands ever become standard tools in classrooms or clinics.

Why inclusive design matters for future workplaces

The study sits in a wider debate about who benefits from new technology. Previous work has shown that speech recognition systems can mishear users with darker skin or strong accents, and that some augmented reality tools perform less reliably on darker skin tones.

Crash test dummies and seatbelts were long tuned to “average” male bodies, leaving women at higher risk in car accidents, while power tools shaped for right-handed grips have contributed to more accidents among left-handed users.

Motor augmentation could end up in the same trap unless inclusivity is built in from the start. The same family of technologies includes exoskeletons that help workers lift and carry heavy loads with less strain, and extra robotic limbs that might assist on factory floors or in operating rooms.

Researchers note that these systems could improve productivity and safety in industries such as construction and manufacturing, while also offering new options for people with disabilities who want to interact more easily with their surroundings.

In practical terms, that might one day mean a technician using a Third Thumb style device to hold cables while tightening bolts, or a lab worker reducing awkward wrist positions that over time can lead to injury. Fewer strained joints and fewer sick days are not just good for individual health. They also contribute, in a modest but real way, to more sustainable workplaces where people and equipment both last longer.

A first step, not the final word

Science Magazine has already highlighted the project, describing the Third Thumb as a robotic appendage that proved “a big hit” with members of the public, which hints at how ready people may be to experiment with body augmentation when it feels intuitive and playful.

At the same time, the authors are clear about what this study does not yet cover. They measured only first-time use, not long-term learning. They also had limited data on factors such as disability and ethnicity, even though these clearly matter for real-world accessibility.

Future work will need larger, deeper samples to see who ends up thriving with augmented tools after weeks or months of practice.For now, the message is simple. With thoughtful, inclusive design, even a radical idea like an extra robotic thumb can feel natural to almost anyone in under a minute.

The study was published in Science Robotics.