Most of us spend the day tossing out words without thinking about how they fit together. We text, we talk, we grumble in traffic. Every sentence quietly combines pieces of meaning. Now, scientists working deep in the rainforests of the Democratic Republic of Congo say wild bonobos are doing something surprisingly similar with their calls. Their findings suggest that a key ingredient of human language may be far older, and far less human, than we thought.

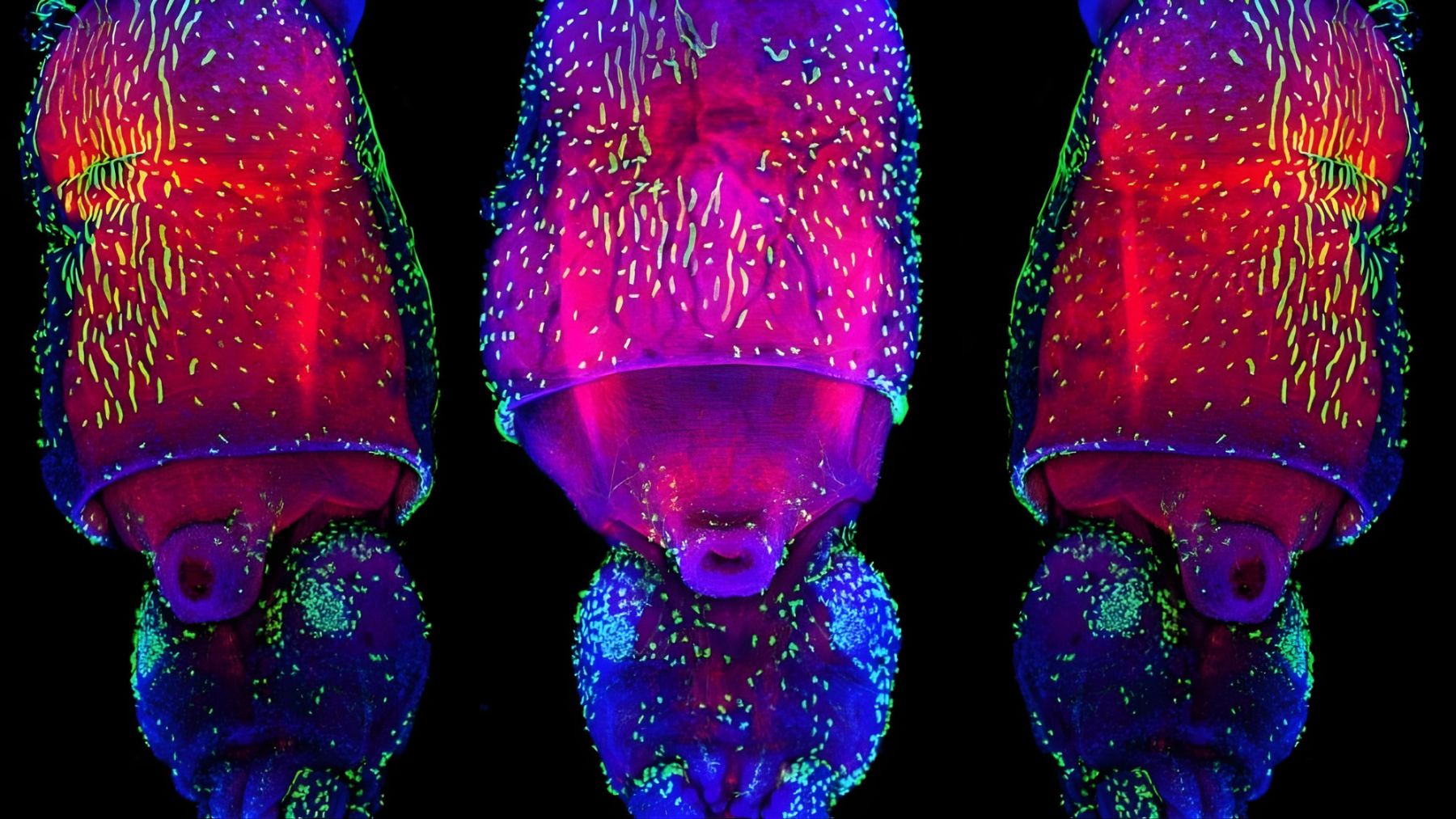

A team from the University of Zurich and Harvard University recorded hundreds of vocal exchanges in the Kokolopori Community Reserve, a community managed forest that shelters one of the largest remaining bonobo populations.

By treating bonobo calls the way linguists treat words, they found that these great apes string sounds together into what are, in effect, mini phrases. Some of those phrases seem to carry meanings that are not just the simple sum of their parts, a pattern once considered unique to human speech.

What bonobo “sentences” look like

To understand why this matters, it helps to look at how we use words. Say “tall musician” and you are basically stacking two ideas. Change that to “bad dancer” and the word “bad” reshapes the idea of “dancer”. The whole phrase means more than just “bad” plus “dancer”. Linguists call this richer kind of mixing ‘nontrivial compositionality’.

The new study argues that bonobo calls show the same pattern. Individual sounds already had consistent meanings. One common soft call, a “peep”, often showed up when an animal appeared to be signaling a wish or intention. A longer “whistle” tended to be used when the group needed to stay coordinated over distance.

Put together as a “peep whistle”, the combination appeared in socially tense moments such as mating or dominance displays and seemed to convey something closer to “let us stay together, let us keep the peace”. That combined meaning could not be reduced to a simple addition of “I would like” plus “stay together”.

A jungle dictionary built call by call

Getting there took a lot more than a few lucky recordings. Researchers followed several habituated bonobo communities in Kokolopori for long days in the forest, often twelve to fifteen hours at a stretch, without interfering with the apes’ normal routines.

For every sound they captured, they noted hundreds of details about the situation such as who was nearby, whether food was present, whether the group was resting, moving or feeding, and whether neighbors were in earshot. In total they analyzed around seven hundred vocal events and more than three hundred contextual variables for each one.

With that huge data set, the team used a technique from linguistics known as distributional semantics. In simple terms, they asked which calls kept showing up in similar situations. That allowed them to sketch a sort of “meaning map” and build a small dictionary of the seven most common call types.

They then looked at how those calls appeared in combinations. Every call turned up in at least one multi-call sequence, and four distinct structures behaved like compositional phrases. Three of those showed the nontrivial pattern in which one element modifies the meaning of the other.

Why complex calls matter for bonobos and for us

For bonobos, this is not an abstract language game. They live in fission-fusion societies, where a community of dozens of animals breaks into smaller foraging parties during the day and reunites later. Keeping track of who is where, who is tense, and who is ready to move is a daily challenge in dense, humid forest where you cannot always see your neighbors.

Many of the calls in the new “dictionary” help coordinate movements and maintain cohesion, a kind of forest group chat that lets individuals stay in sync as they spread out to feed.

At the same time, the results speak directly to human origins. Bonobos and humans share a common ancestor that lived roughly seven to thirteen million years ago. If both species use compositional structures in their vocal systems, that capacity likely existed in that ancestor too, at least in a simpler form.

The researchers argue that compositionality in communication is therefore evolutionarily ancient and that our elaborate sentences may have grown from building blocks already present in great ape calls.

Other experts are cautiously enthusiastic. Some suggest that certain bonobo phrases could function more like idioms, where the meaning of the whole is not fully predictable from its parts.

Even so, the mathematical tests used in the study, which are standard in human language research, point strongly toward nontrivial compositionality in at least a few of the combinations. In other words, bonobo communication may not be a language in the human sense, yet to a large extent it seems to follow one of language’s core principles.

Language clues in a threatened forest

All of this depends on one fragile thing. The forest itself. Bonobos are an endangered species, found only in the lowland rainforests south of the Congo River. Their populations are shrinking under pressure from habitat loss, logging, and hunting for bushmeat. Only a fraction of their range is formally protected, and community reserves like Kokolopori play a crucial role in keeping both bonobos and their forest home standing.

At the end of the day, every new insight into bonobo communication is also a reminder of what is at stake when tropical forests are cleared. Lose these apes and we lose one of the last living windows into how our own astonishing capacity for language began.

The study was published in Science.