Using one of the most sensitive radio telescopes on Earth, astronomers have found an extreme kind of “star factory” in the very young universe.

The distant galaxy MACS0416_Y1, or simply Y1, is forming new stars about 180 times faster than the Milky Way while its clouds of cosmic dust glow at unusually high temperatures. The discovery helps explain how early galaxies bulked up so quickly and why they appear to contain so much dust.

Y1 sits at a redshift of about 8.3, which means we see it as it was only around 600 million years after the Big Bang. Its light has traveled for more than 13 billion years to reach our telescopes, so every pixel in the image is a time capsule from the universe’s childhood.

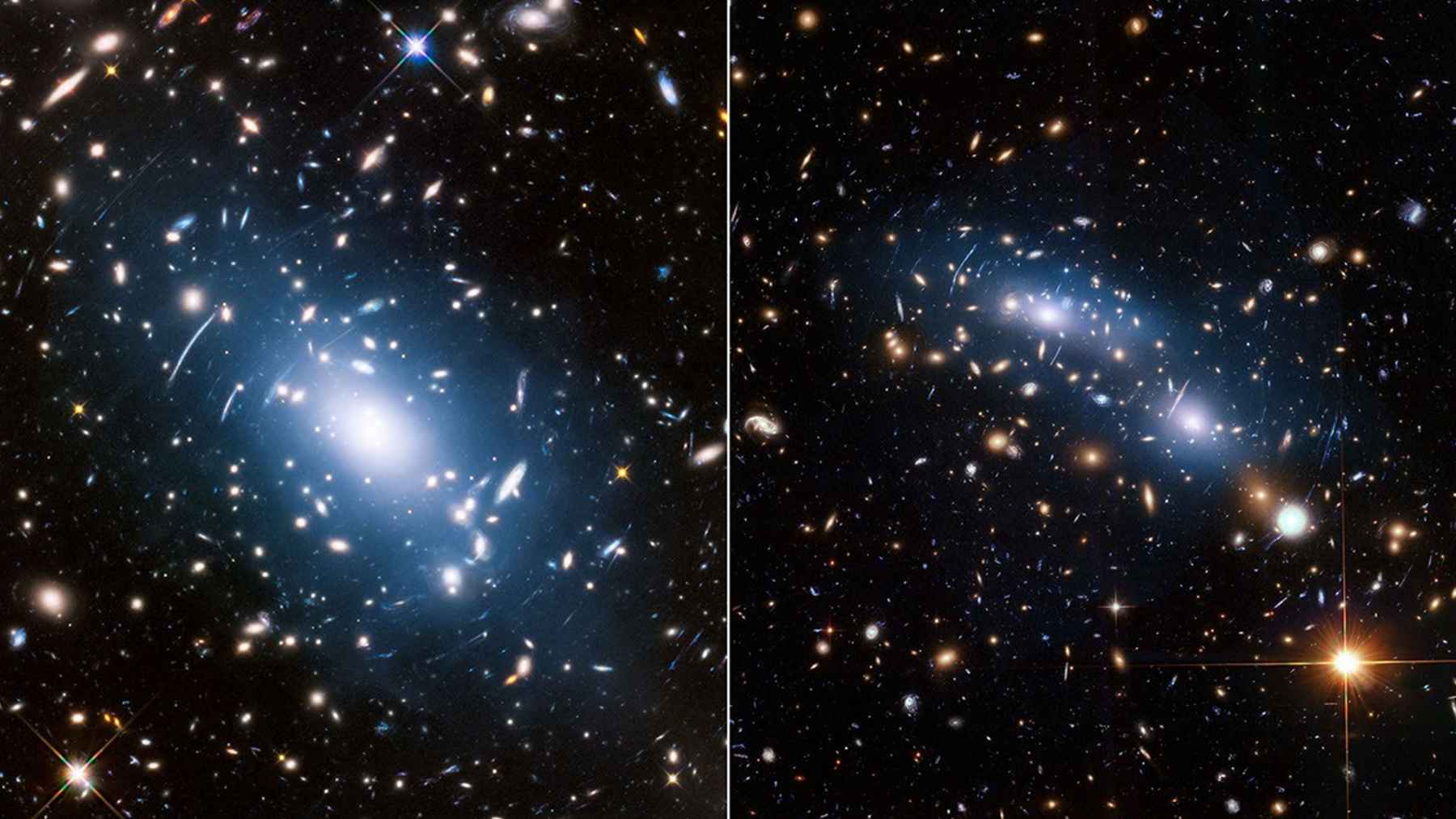

Gravitational lensing by a closer galaxy cluster in the constellation Eridanus magnifies Y1 just enough for observatories like ALMA and the James Webb Space Telescope to pick it out as a faint, deep-red smudge in the background.

A galaxy that outpaces the Milky Way

In our own galaxy, stars form at a modest pace, roughly one Sun’s worth of material per year. In Y1, the story is very different.

New measurements show that this compact system is turning gas into stars at more than 180 solar masses per year, putting it in the elite class of ultraluminous infrared galaxies, or ULIRGs, with infrared power close to a trillion times the brightness of the Sun.

“If the Milky Way is a quiet neighborhood workshop, Y1 behaves more like a giant factory operating around the clock.” In practical terms, that furious activity cannot last very long by cosmic standards.

Astronomers think they are catching the galaxy during a brief growth spurt that may last only a few tens of millions of years before the gas supply thins out and the starburst fades.

To understand what powers this outburst, the team used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. They targeted Y1 at a wavelength of 0.44 millimeters with ALMA’s high frequency Band 9, which works especially well in the dry, high altitude air of the Atacama Desert.

By comparing this new detection with earlier ALMA data at longer wavelengths, the researchers could fit a curve to the dust emission and read off its temperature. The answer surprised them. The dust in Y1 is about 90 Kelvin, roughly minus 180 degrees Celsius, much warmer than dust typically seen in galaxies at similar distances.

“We are looking back to a time when the universe was making stars much faster than today,” said lead author Tom Bakx, who led the study. That hectic pace floods the galaxy with intense ultraviolet light from newborn, massive stars, which in turn heats nearby dust grains to these unusually high temperatures.

Solving the early cosmic dust puzzle

For years, astronomers have wrestled with a puzzle. Young galaxies in the early universe seem to contain more dust than their limited number of older stars should be able to produce. If those dust grains were all cold, you would indeed need enormous amounts of material to explain the observed glow.

Y1 points to a different answer. Because warm dust radiates much more efficiently than cold dust, even a relatively small quantity of hot grains can shine as brightly as a huge mass of cooler material.

As astrophysicist Laura Sommovigo explained, “a small amount of warm dust can be just as bright as a large amount of cool dust,” so earlier measurements may simply have overestimated how much dust is really there.

That adjustment matters. Dust is made from heavy elements such as carbon, silicon, oxygen, and iron, forged inside stars and released in stellar winds and supernova explosions.

Tiny grains, often starting out as carbon or silicate particles, go on to collect ices and simple organic molecules on their surfaces and help drive chemistry between the stars.

From ancient star factories to life on Earth

At first glance, a blazing galaxy more than 13 billion light years away might feel far removed from worries about air quality, ocean health, or the electric bill at home. Yet there is a quiet connection.

The same heavy elements that make up interstellar dust eventually become the rock in Earth’s crust, the iron in wind turbine towers, and the carbon in every tree, plankton cell, and human body. Without earlier generations of intense star factories like Y1, the universe would be poorer in these ingredients and rocky planets like ours would be far less common.

To a large extent, studies of galaxies such as Y1 are telling us how quickly the universe built the raw materials for environments where life can emerge and ecosystems can evolve.

The faster early galaxies turned gas into stars and dust, the sooner later generations of stars could host planets with oceans, soils, and atmospheres. In a sense, the story of sustainable life on Earth begins inside remote, dust-filled nurseries like this one.

Astronomers now plan to search for more galaxies with similarly hot dust and to map Y1 in finer detail, looking for pockets where stars and dust separate on scales smaller than either ALMA or Webb can currently resolve.

Each new “superheated star factory” they find will sharpen models of how galaxies first grew and how quickly the universe recycled gas into stars, dust, and eventually planets.

The study was published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.