When a continent breaks apart, at the surface we see oceans that open very slowly. Under our feet, though, something much more restless is going on. A new study shows that, at depth, a kind of “wave” forms in the mantle that scrapes material from the base of the continents and drags it beneath the oceans for tens of millions of years.

Why should this matter to anyone paying attention to climate, volcanoes, or CO₂? Because that recycled material feeds part of oceanic volcanism and forms part of the big “internal circuit” that moves carbon and other key elements between the planet’s interior and its surface. At the end of the day, it helps explain how Earth is organized inside and why some remote volcanoes have such strange chemistry.

A deep wave that scrapes the roots of the continents

Beneath every continent there is a rigid root of cold, ancient rock, denser and more chemically “spiced” than the mantle that surrounds it. It is like the thick sole of a shoe that sinks a bit deeper into the inside of the planet.

The team led by Thomas Gernon combined numerical models and geochemical data to show that when major rifting begins (that is, when a continent starts to tear apart), a chain of mantle instabilities organizes at the base of those roots.

Put simply, a “mantle wave” forms that advances very slowly beneath the continent. That wave peels off small enriched fragments from the continental root and injects them into the mantle beneath the new ocean. Some of that material can travel more than a thousand kilometers before melting and reappearing as lava on islands and seamounts.

The models also indicate that this supply is neither instantaneous nor a one‑off. Typically, there is a peak in the delivery of enriched material within the first forty or fifty million years after continental breakup, followed by a gradual decline. In geology, that is almost “right away”.

Ocean islands with a continental fingerprint

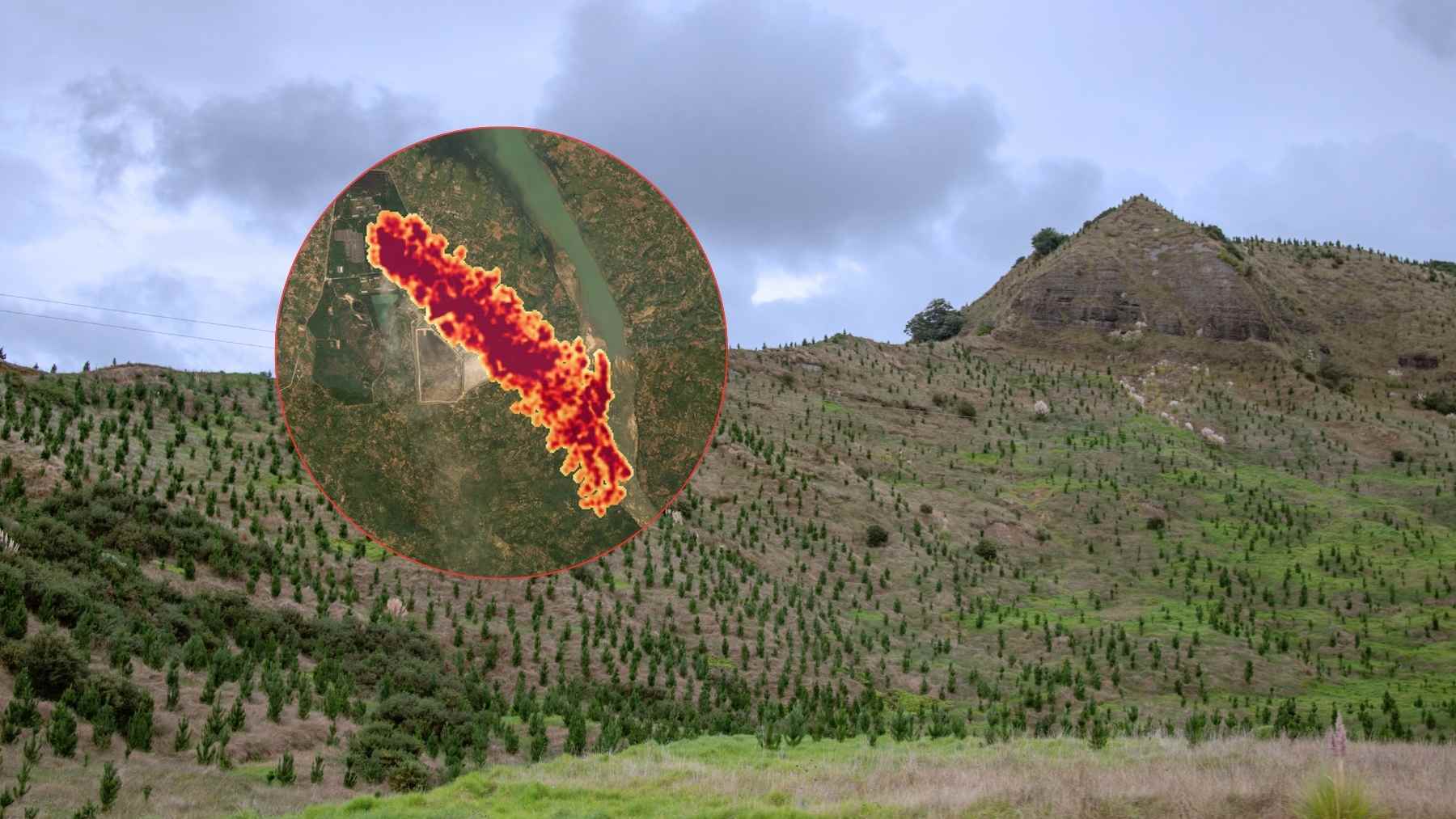

The theory has been tested in a very particular natural laboratory in the Indian Ocean. There, west of Australia, there is an entire province of seamounts and small islands whose lavas have a clearly continental chemical signature. Yet they sit in the middle of an oceanic plate and far from the big hot plumes that rise from the deep mantle.

The new work puts the pieces of this puzzle together. The team shows that, after the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana more than one hundred million years ago, enriched volcanism in that area reached a maximum within the first fifty million years and then gradually “dimmed” chemically over time, exactly what the models of that wave scraping the continental root predict.

In practice, that means many volcanic islands we see today rising over deep oceans are, to a large extent, made of material that started its life beneath a very distant, very ancient continent.

One more cog in the deep carbon cycle

All of this may sound very abstract compared with your power bill or the sticky heat waves we already feel every summer. But it has a direct connection to how Earth regulates CO₂ and other gases over millions of years.

The continental roots being scraped are enriched in hydrated and carbonated minerals. When those fragments sink, heat up, and start to melt beneath young, thin oceanic crust, they release volatiles that feed volcanoes. Part of that CO₂ ends up in the atmosphere and part goes back into the ocean or becomes trapped in new rocks.

This is not a process that competes with human emissions on the timescale that matters to us. Burning fossil fuels changes the climate in decades. These “mantle waves” act over periods of millions of years. But if we really want to understand how the planet breathes in the long term, these mechanisms are an essential piece.

A mantle less static than it seems

The study also tackles something that until now was almost always attributed to large hot plumes rising from great depth. Part of the chemical diversity we see in island and hotspot lavas can be explained by this lateral recycling of continental roots, without always needing to invoke very deep processes.

The authors suggest that, during and after continental breakup, the entire upper mantle is reorganized. That reorganization leaves a “diffuse pool” of ancient material beneath the oceans, which is gradually consumed in different volcanic episodes. To a large extent, it is a way of connecting what happens along the edges of continents with what happens much later on islands lost in the middle of the sea.

In short, the classic picture of the mantle as something rather static falls away. Beneath the crust, continental roots are eroded, ripped apart, and recycled in a slow back‑and‑forth that affects volcanoes, the oceans, and the deep carbon cycle, and even links to how volcanic ash can be reused in clean energy technologies.

The study was published in “Nature Geoscience” and can be consulted at this official link: Enriched mantle generated through persistent convective erosion of continental roots.