A 300,000-year-old jawbone from a cave in eastern China is quietly reshaping what scientists thought they knew about our origins. Fresh analysis of the Hualongdong mandible, known as HLD 6, reveals a surprising mix of traits seen in both earlier humans and people like us.

In simple terms, this young individual had a jaw that partly looked like a modern human and partly like a more archaic ancestor. That combination appears in East Asia much earlier than many researchers expected.

A jaw that almost has a chin

If you touch your own chin, you are feeling one of the classic hallmarks of Homo sapiens. Earlier human species do not really have it. HLD 6 comes close, but not all the way.

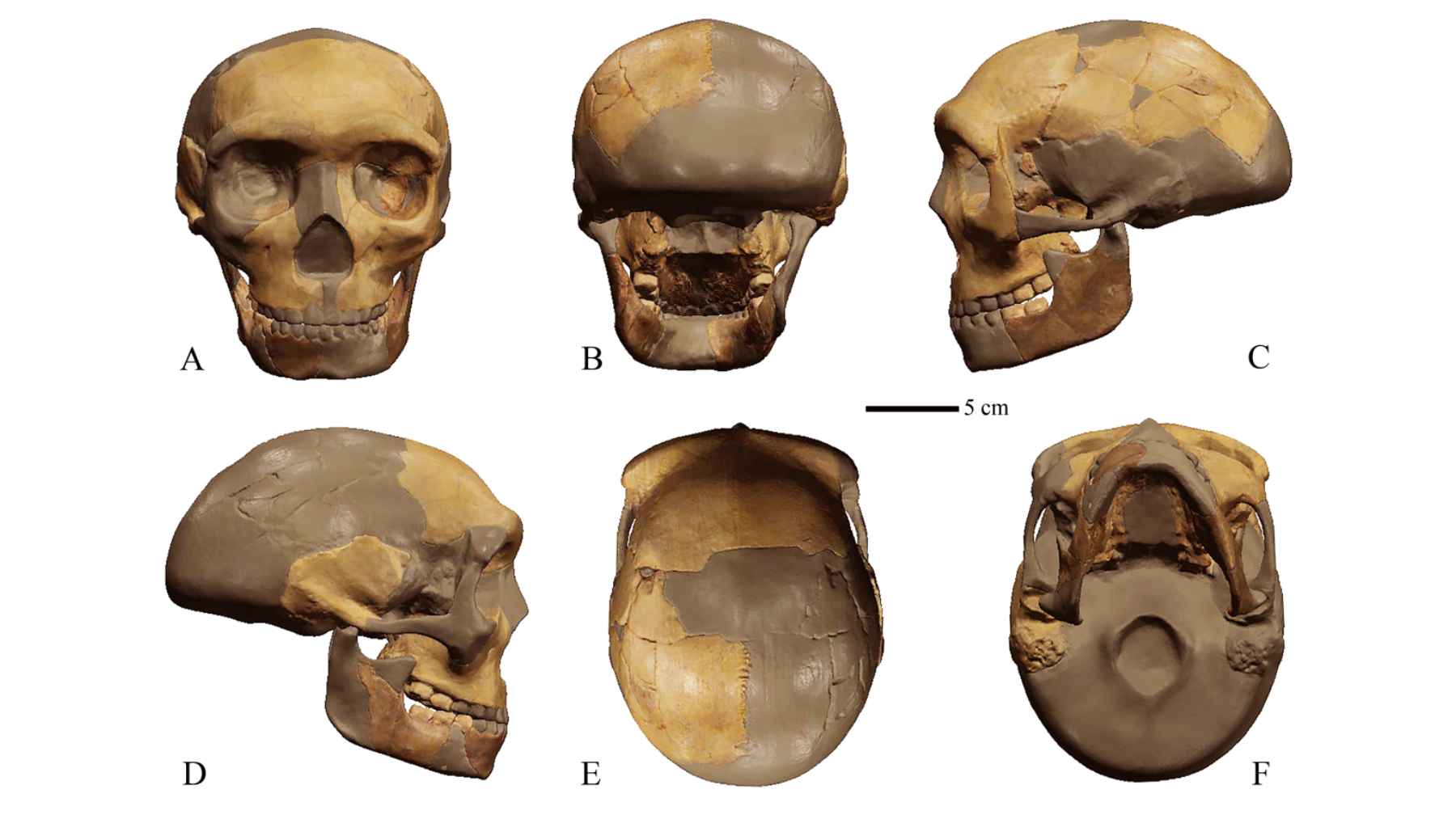

The new study, led by Xiujie Wu and colleagues from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and international partners, shows that the mandible has a robust lower edge yet a relatively slender front and upward branch.

The team describes a moderately-developed mental trigone and a clear inward curve at the front of the jaw, features that echo the beginnings of a human chin, although the fossil still lacks a fully modern one.

At the same time, the jaw carries a full suite of older traits. It has a thick body, a strongly developed inner crest near the jaw joint and a pronounced area for muscle attachment inside the jaw. These details match Middle Pleistocene archaic humans more than they match recent people.

So HLD 6 is neither fully archaic nor fully modern. It sits in between, with what scientists call a mosaic pattern of anatomy.

A teenager from a crowded cave

The fossil comes from Hualongdong in Anhui Province, a limestone area that once sheltered a sizable community of ancient humans. Excavations have recovered about 30 fossils from at least 16 individuals, alongside animal bones and stone tools, all dated to roughly 300 thousand years ago.

Earlier work on the HLD 6 skull showed a relatively flat face and other features that lean toward modern humans, again mixed with more primitive elements in the braincase.

HLD 6 was not an adult. Dental development suggests an age of around 12 to 13 years, a teenager by our standards. That raised an obvious question. Could the unusual jaw simply reflect the fact that it was still growing

To check, the researchers compared the mandible with both adult and immature fossils from other sites and with modern human children. The pattern stayed the same. Even when age was taken into account, HLD 6 did not match typical growth stages of known species.

In other words, this is not just a quirky teenage jaw.

A crowded family tree in Ice Age Asia

For many years, textbooks often treated human evolution in China as a fairly straight line, running from Homo erectus to so-called archaic Homo sapiens and then to modern East Asians.

The last two decades have chipped away at that simple story. New finds such as Dali, Jinniushan, Xiahe and Harbin all carry different blends of traits that are hard to fit into neat species boxes.

HLD 6 pushes that complexity even further. The study notes that its mix of archaic and modern features does not closely resemble other Middle Pleistocene fossils of similar age from East Asia, including Xujiayao, Penghu and Xiahe.

Some researchers now argue that several human lineages probably shared the region at the same time. In this view, only some of those groups contributed directly to our own species.

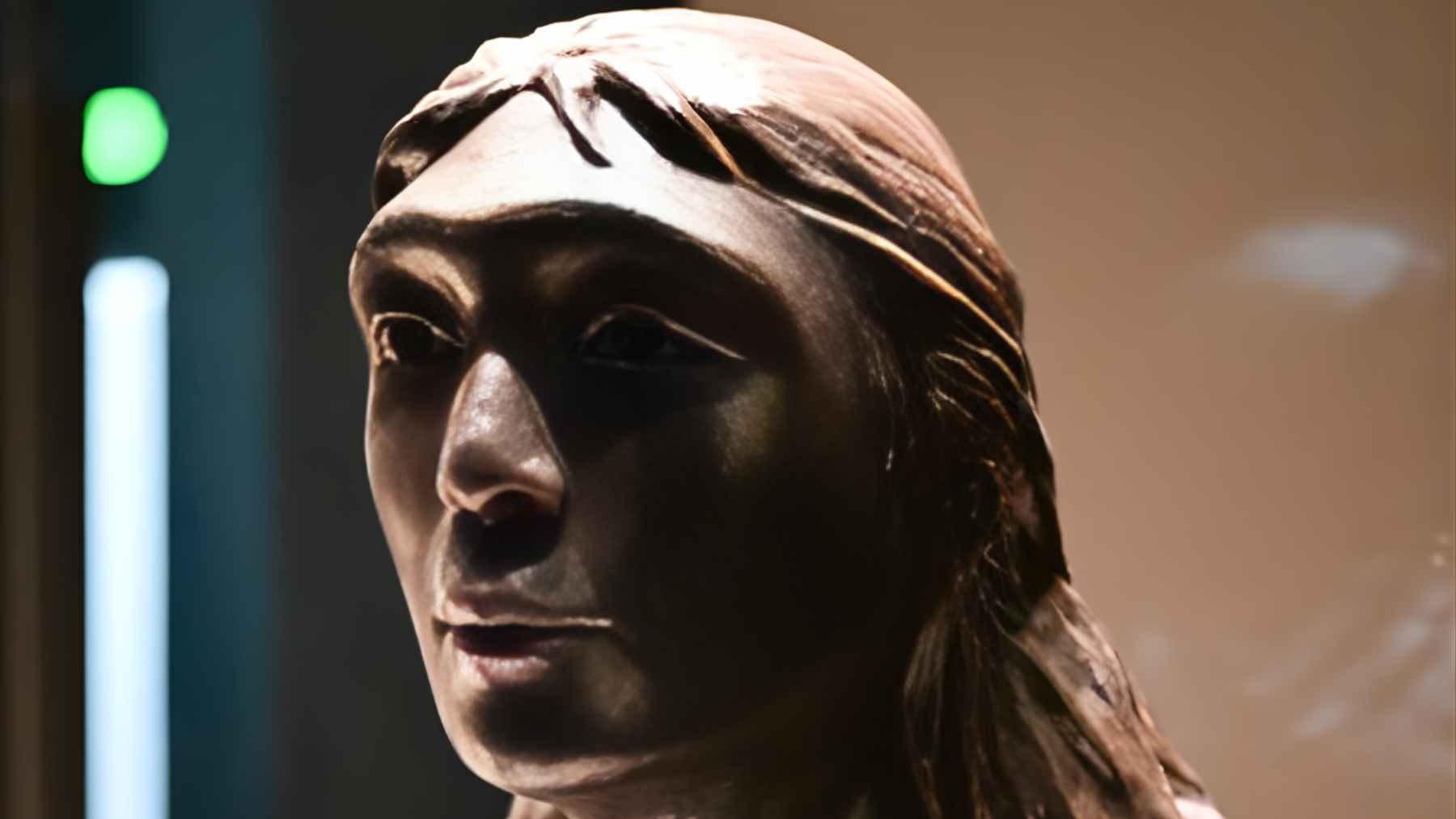

The new analysis suggests that the Hualongdong people might belong to a lineage closer to the root of Homo sapiens in East Asia, similar in importance to the Jebel Irhoud fossils in North Africa or the Misliya remains in the Near East.

It is an intriguing idea, although experts stress that without ancient DNA or proteins from HLD 6, its precise place on the family tree remains uncertain.

What this means for the face in the mirror

Why should anyone outside a paleo lab care about the curve of a fossil jaw in a cave half a world away?

Because it quietly reminds us that our species did not appear overnight. Traits we take for granted today, such as a projecting chin or a relatively flat face, seem to have emerged piece by piece, in different places and at different speeds.

Hualongdong shows that some of those changes were underway in East Asia at least 300,000 years ago, long before fully modern humans show up in the region.

The teenager who owned this jaw likely chewed tough food, spoke with a voice shaped by that not-quite-modern chin and lived in a landscape shared with other hominin groups.

In many ways, their world was harsh. Yet their bones now help answer the everyday questions we still ask about ourselves, from who we are to where we came from.

The study was published in the Journal of Human Evolution.