Could the secret to blowing out 100 birthday candles be hiding in DNA that dates back to the last Ice Age? A new genetic study from Italy suggests that people who live to 100 and beyond carry slightly more ancestry from ancient European hunter gatherers than their peers.

The work links survival skills from harsh glacial winters to modern extreme longevity, adding a surprising twist to the usual talk about diet, exercise, and luck.

Researchers led by Cristina Giuliani at the University of Bologna analyzed genome-wide data from 333 Italian centenarians and 690 geographically matched adults, then compared their DNA with 103 ancient genomes that summarize the main ancestral sources in Europe.

Everyone in the study carried a blend of old lineages, including early farmers from Anatolia, steppe herders, and populations related to the Iranian Caucasus. What stood out was one specific component.

Centenarians showed a stronger pull toward Western Hunter Gatherer ancestry, a genetic lineage tied to Ice Age Europeans who lived in the continent long before farming spread.

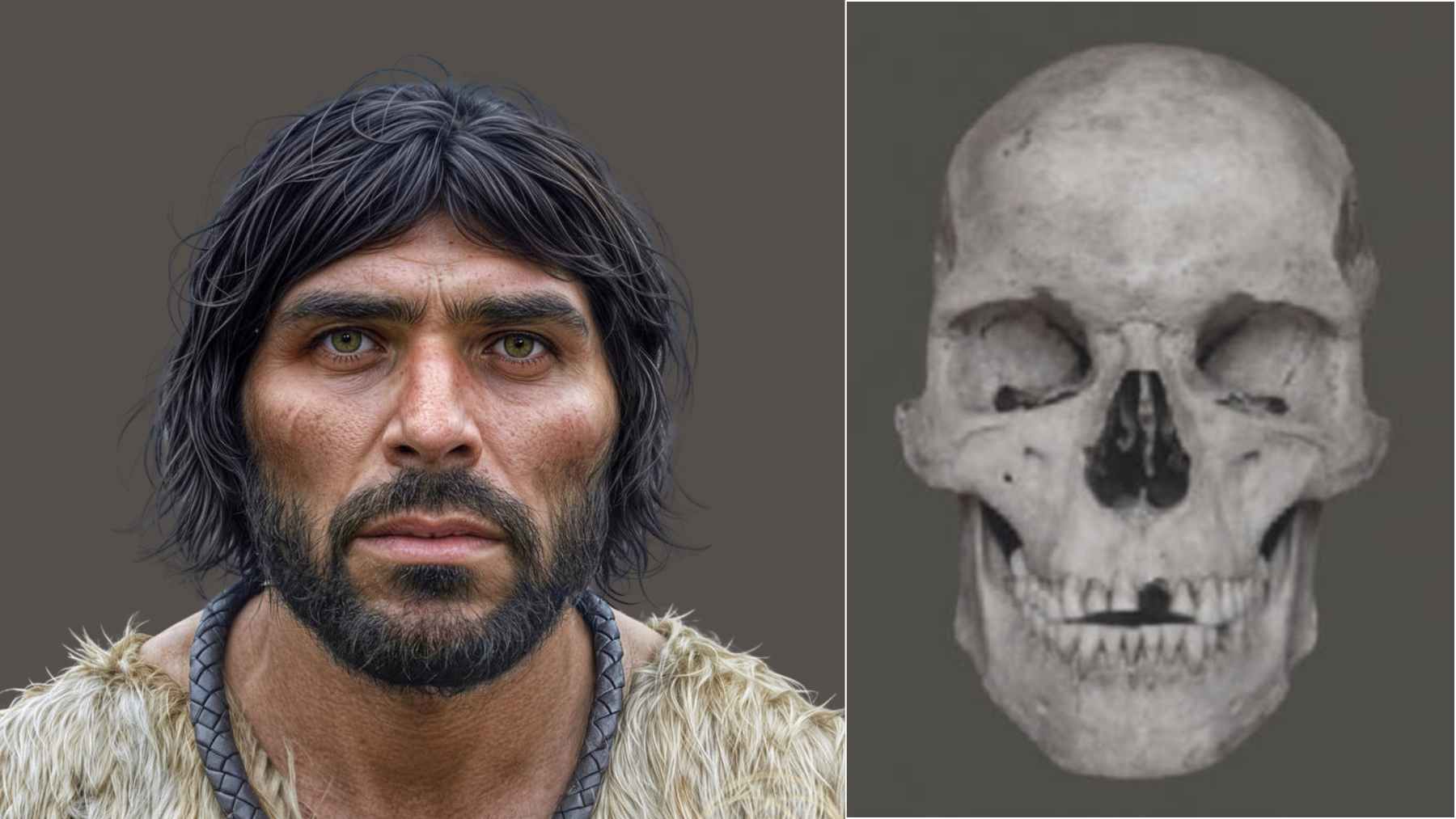

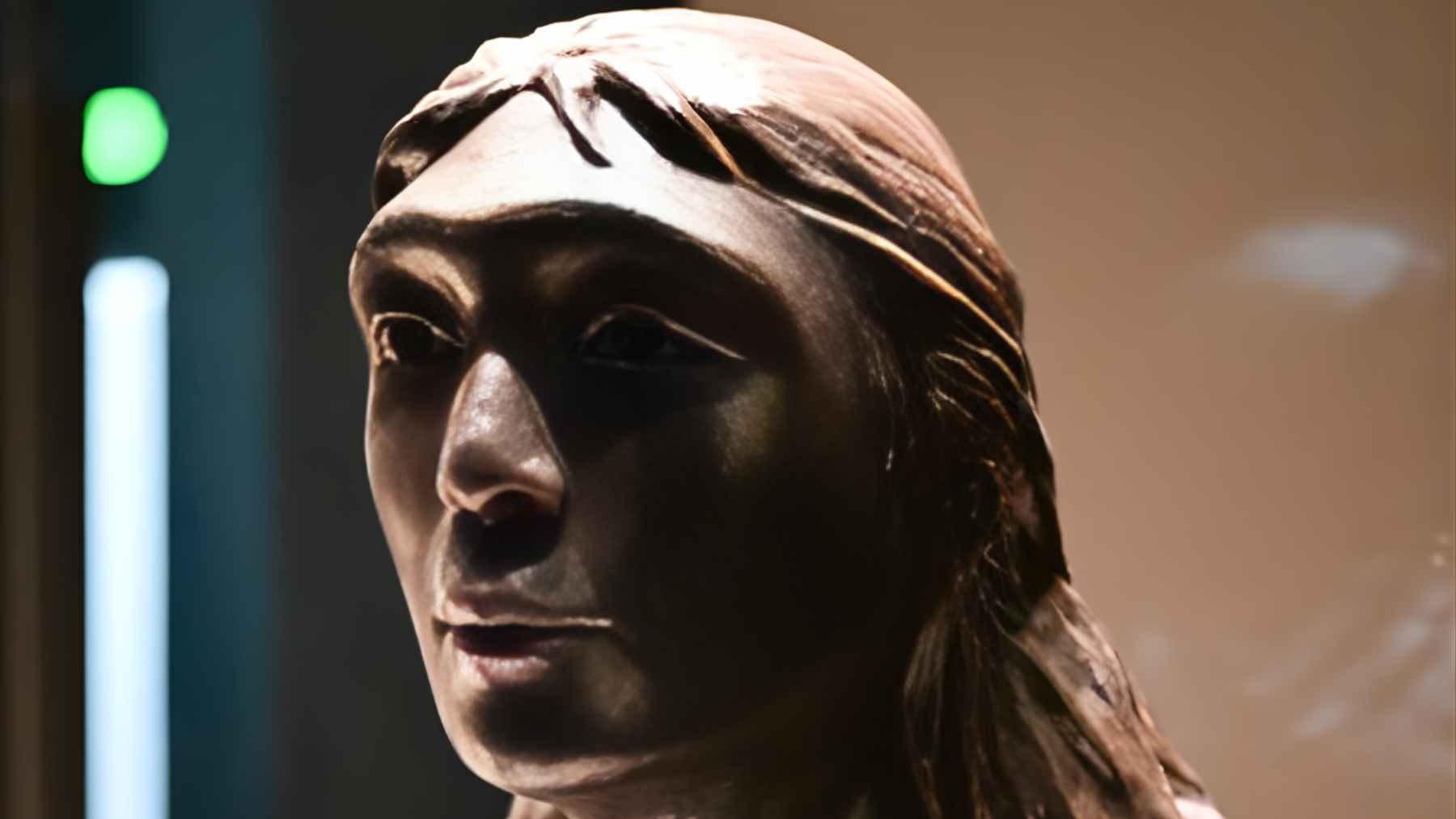

Western Hunter Gatherers are known from ancient remains such as the Villabruna cluster in northern Italy, dated to roughly 14,000 years ago. These groups hunted, fished, and gathered through some of the coldest phases of the last glaciation, surviving on scarce food and coping with frequent infections in crowded camps and caves.

The new study suggests that pieces of their DNA still echo in modern Italians and may slightly tilt the odds toward a longer life. As the authors put it, “In the present study, we demonstrate the contribution of ancient genetic components to the longevity phenotype.”

To move beyond broad ancestry labels, the team looked at how specific chunks of DNA cluster along chromosomes. They asked whether regions that favor extreme old age carry more variants from one ancestral source than expected.

The answer pointed again toward Western Hunter Gatherers. Centenarians carried more hunter gatherer derived versions of several known pro-longevity variants, small DNA changes that can nudge protein signals involved in metabolism, immunity, and cellular repair.

Using statistical models, the researchers estimated that a higher share of Western Hunter Gatherer ancestry was linked to roughly 38% higher odds of belonging to the centenarian group, even after adjusting for the north to south genetic structure within Italy.

In everyday terms, that is a modest bump in probability rather than a guarantee, but it is strong enough to show up across repeated tests and different analytical approaches.

Italy offers an unusually good testing ground for this kind of work. The peninsula sits at a crossroads of ancient migrations, so modern Italians carry a layered mix of ancestral components.

Official statistics recorded 23,548 residents aged 100 or older on the first day of 2025, and almost 83% of them were women. That large pool of very old adults, combined with well-studied regional genetic patterns, makes it easier to ask whether certain deep ancestries are slightly over-represented among people who reach triple digits.

The signal was clearest in women, which fits real-world demographics where women usually dominate centenarian counts. At the same time, the study included far fewer long-lived men, so the authors caution that they cannot yet say whether the same pattern holds for both sexes.

Larger datasets that include more male centenarians will be needed to tease apart biology, social history, and simple sampling noise.

Why might Ice Age genes matter for aging today? One idea is that variants favored during the Last Glacial Maximum helped bodies store energy efficiently and mount fast immune responses against infections. In the 21st century, some of those differences may help keep chronic inflammation in check.

Scientists sometimes call this slow-burn immune activity “inflammaging” because it rises with age and is linked to heart disease, diabetes, and dementia. If hunter gatherer variants gently dampen this process, they could support healthier aging, at least to a small extent.

The authors stress that ancestry is not destiny. Human longevity depends on many biological pathways and on a lifetime of environmental exposures, from childhood nutrition to air quality and access to healthcare. Italy also has strong regional contrasts in culture and income, which can move in step with genetics and confuse simple stories.

The team adjusted their analyses for known population structure, yet they note that only further laboratory work and independent studies in other countries can confirm whether Western Hunter Gatherer variants actively shape aging rather than simply tagging along with some hidden factor.

For now, the findings offer a striking eco-evolutionary snapshot of how ancient environments may still echo in modern bodies. The same genetic tweaks that once helped people endure brutal winters and scarce game may, to a limited extent, support resilience in old age, long after campfires and ice sheets vanished.

Lifestyle choices still matter for the electric bill, the morning walk, and the yearly check up, yet this work shows that deep history quietly shares the stage.

The study was published in GeroScience.