A giant tortoise that scientists once filed under “extinct for more than a century” has turned out to be very much alive, slowly roaming one of the harshest corners of the Galápagos Islands.

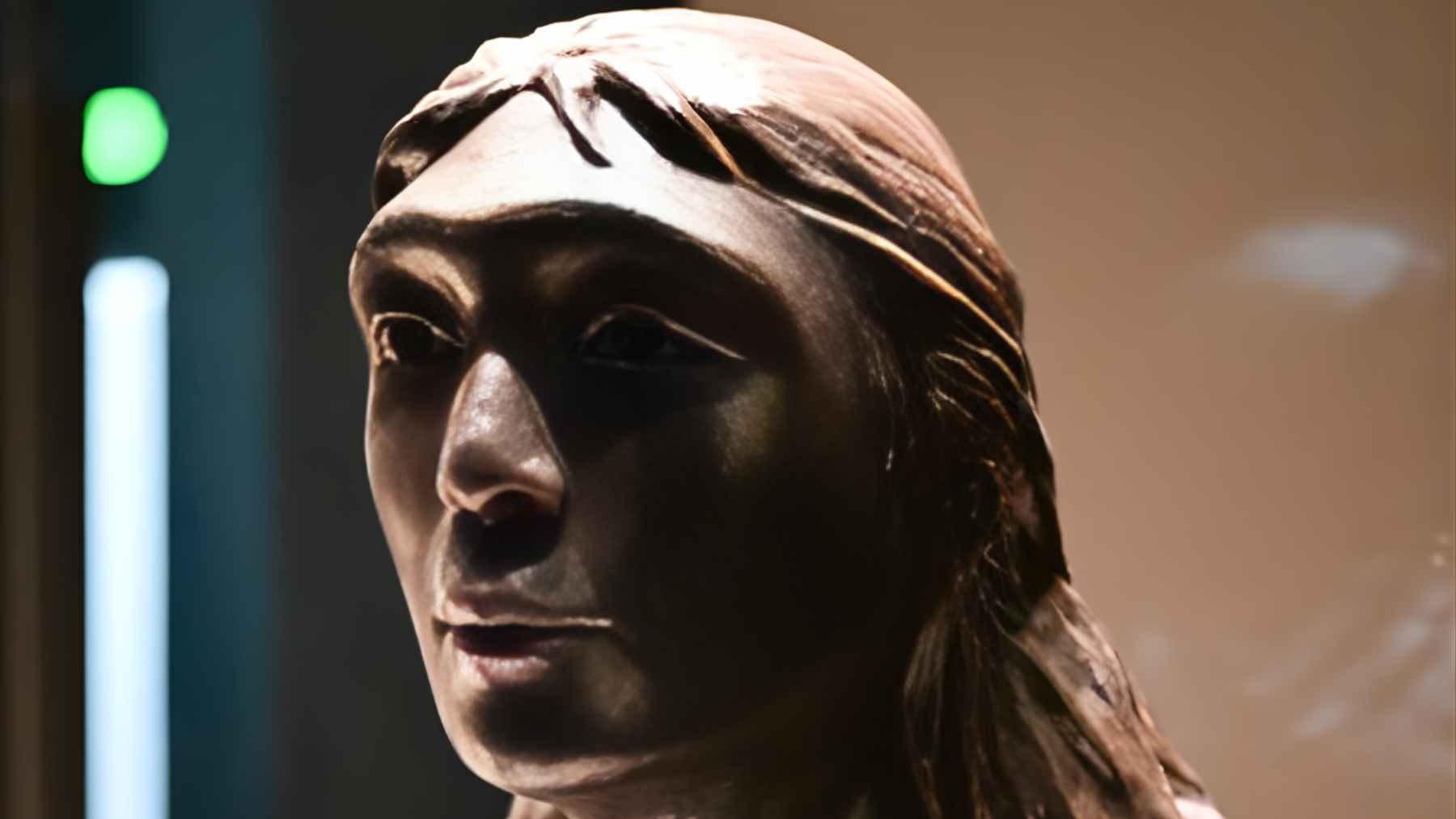

The female, nicknamed Fernanda, was discovered in 2019 on Fernandina Island, a young volcanic island in Ecuador that is largely carpeted in fresh black lava.

Genetic sleuthing has now confirmed that she belongs to the Fernandina Island Galápagos giant tortoise, Chelonoidis phantasticus, a lineage thought lost since a lone male was collected in 1906.

Only two individuals of this lineage have ever been found, the museum specimen from the early twentieth century and Fernanda. To make sure she was not a stray tortoise washed in from another island, researchers sequenced her entire genome and compared it with DNA extracted from the century-old male and from all other living Galápagos tortoise species.

The analyses showed that Fernanda and the museum male form their own distinct branch, separate from the rest of the archipelago’s giants.

That might sound like a technical detail, yet it carries a huge message. It confirms that a lineage written off as extinct has survived in secret for decades, perhaps longer, on a remote volcano where even experienced field biologists struggle to move across the jagged lava.

Fernanda was found in a small, scrubby pocket of vegetation cut off from greener areas by old flows, a spot easy to miss on foot and nearly invisible from the air.

Fernanda herself does not look quite like the dramatic “saddleback” tortoise preserved in the collections of the California Academy of Sciences. Her growth appears stunted, which likely warped some of the shell features taxonomists normally use to tell lineages apart.

That is one reason genetic confirmation mattered so much. It shows how relying on appearance alone can be risky when only a handful of individuals remain.

The study, led by scientists from Newcastle University, Princeton University and Yale University, did more than place Fernanda on the family tree. It also hints at a bigger question. If one “extinct” giant tortoise can survive undetected on an island that has been surveyed multiple times, how many other rare species are quietly hanging on in places we check only briefly?

Field teams on Fernandina have already reported tracks and droppings that look like they came from at least two or three other tortoises. Those clues are not proof, but they are enough to justify new expeditions into the island’s dangerous interior, where fresh lava, sudden weather shifts and limited landing sites make every search feel like a race against both geology and time.

As one of the lead authors, Dr Evelyn Jensen, put it, “It is a truly exciting discovery that the species is not in fact extinct, but lives on.”

Today Fernanda lives under human care at the giant tortoise breeding center run by the Galápagos National Park Directorate on Santa Cruz Island.

A Princeton summary describes her new home this way, “Fernanda, the only known living Fernandina giant tortoise, now lives at the Galápagos National Park’s Giant Tortoise Breeding Center on Santa Cruz Island.” There she receives veterinary checks and round the clock monitoring while scientists debate the safest path forward.

The stakes go far beyond one elderly reptile. Giant tortoises once dominated these islands. Historical accounts and modern reconstructions suggest that at least a quarter of a million animals roamed the Galápagos before intensive hunting by sailors and whalers. Today only around fifteen thousand remain in the wild, spread across a patchwork of surviving subspecies.

Those numbers explain why every rediscovered lineage matters. In practical terms, the genome data for Fernanda and the museum male give conservation planners a solid baseline to measure genetic diversity and to avoid inbreeding if more individuals are found and a breeding program becomes possible.

Without that information, any attempt to rebuild the population would be flying blind.

At the same time, Fernanda’s story highlights a sobering reality that many conservation biologists know well. A species can persist for decades as just a handful of scattered survivors, technically alive yet one unlucky fire, storm or disease outbreak away from disappearance.

Lonesome George, the last Pinta Island tortoise, showed what happens when no mate is ever found. Fernandina’s tortoise could follow the same path if future searches come up empty.

For people reading this far from the lava fields, the lesson may feel simple yet uncomfortable. Declaring a species extinct too quickly can erase political urgency to protect its habitat.

Waiting too long can mean help arrives when only one or two animals remain. Fernanda sits right on that knife edge, a symbol of both hope and how much has already been lost.

The study was published in Communications Biology.