Chinese military researchers have quietly built a compact power system that many outlets are already calling a “Starlink killer.” On paper, it can feed a satellite zapping microwave weapon with more energy than any known device of its kind while staying small enough to ride on a truck.

The device, known as TPG1000Cs, was developed at the Northwest Institute of Nuclear Technology in Xi’an, China and described in a new peer-reviewed paper led by physicist Wang Gang.

The study says the system can sustain 20 gigawatts of pulsed power for a full minute, a huge jump from earlier high-power microwave drivers that typically managed only a few seconds before overheating or running out of stored energy.

What a high-power microwave weapon actually is

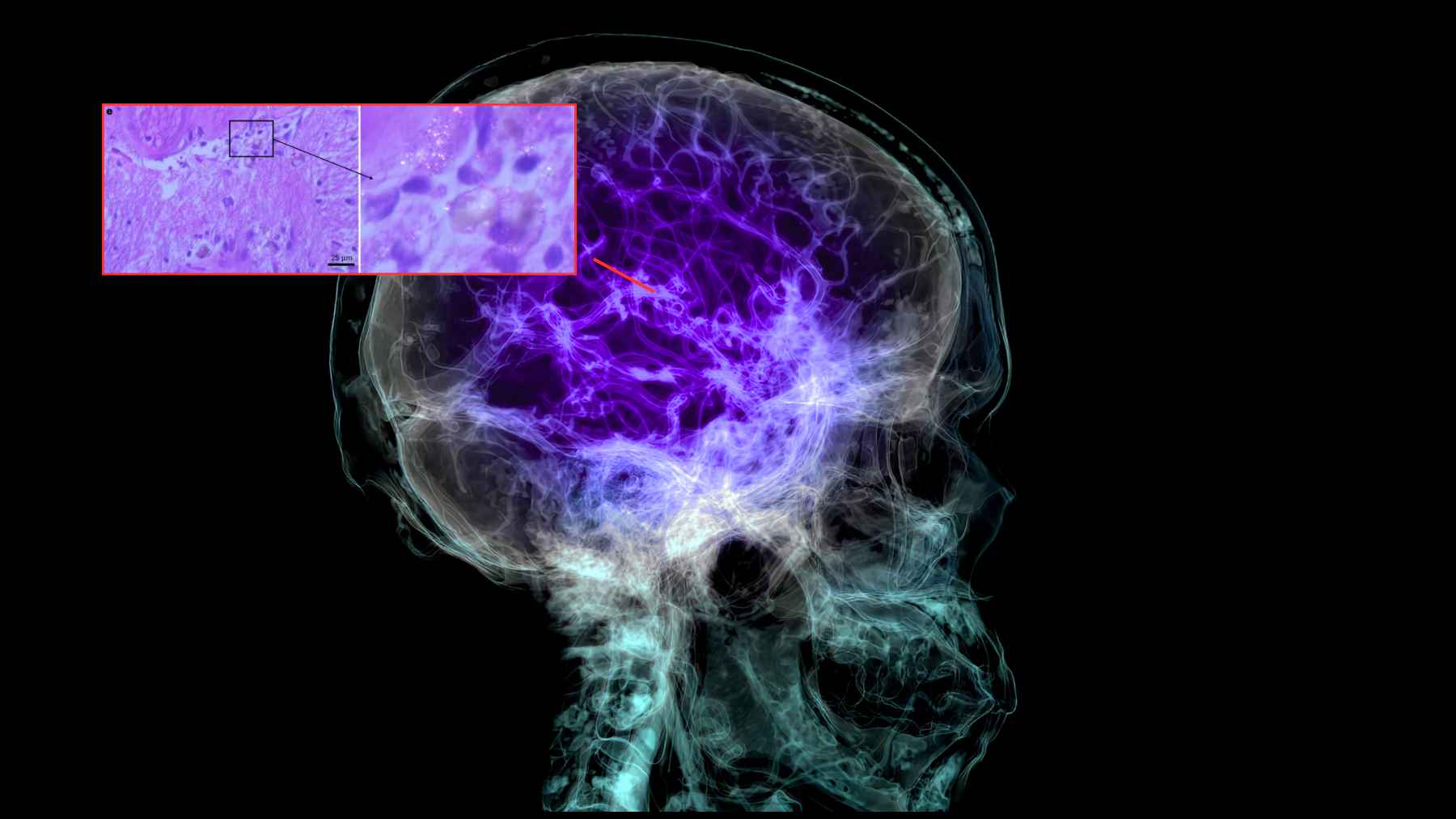

At its core, a high-power microwave weapon uses very intense bursts of radio energy to overload electronics. Instead of punching a hole in a satellite with shrapnel, it aims to scramble or burn out circuits from afar.

Military planners like these systems because they can disable radars, communications links, or satellites without creating clouds of debris that threaten everyone else in orbit.

According to reporting that draws on Chinese modeling, even a one-gigawatt ground system could disturb or damage low-orbit satellites such as the Starlink communications craft that orbit a few hundred miles above Earth.

Russia’s Sinus7 driver gives a sense of how hard this has been to engineer. That older pulsed power unit can run for roughly one second and produce about one hundred microwave pulses, yet it weighs around ten tons and normally works in short bursts in a lab setting.

How China’s TPG1000Cs squeezes 20 GW into a truck-sized box

The Chinese team focused on the pulsed power driver, the part of the weapon that stores electrical energy and then dumps it into a microwave source in very short spikes.

Their TPG1000Cs design is based on a Tesla-type transformer and a special dual-width pulse-forming line that shapes each pulse to about fifty billionths of a second while keeping the output flat and stable.

Instead of standard transformer oil, they use a high-energy density liquid insulator called Midel 7131 and a refined oil impregnation process that helps prevent tiny gas bubbles from sparking and ruining the device.

This lets the hardware store more energy in a smaller volume while improving reliability at very high voltages.

Physically, the driver measures about four meters long and one and a half meters wide and tall, with a total mass near five tons. The housing relies on aluminum alloy to cut weight, and the authors say it has already logged about two hundred thousand pulses across repeated one minute runs, often firing up to three thousand high-energy pulses in a single operating session.

From straight tubes to compact “Starlink killer” design

Earlier high-power microwave drivers tended to use straight tube layouts for their pulse forming lines. Those long cylinders, filled with insulating oil and cables, made systems bulky and difficult to mount on anything smaller than a large trailer or fixed installation.

In TPG1000Cs, the Chinese group replaced that layout with a dual U shaped structure so the energy effectively loops back and forth inside a shorter package while still reaching the required power.

Combined with the better insulating liquid, that shift delivers the same 20 gigawatt level as older gear in roughly half the space and at much lower weight.

This is not a one-off effort either. In 2024, the same group reported a fifteen gigawatt repetitive generator using the same insulating oil in the journal Review of Scientific Instruments, a sign that they have been pushing this compact pulsed power line for years rather than starting from scratch.

Why satellite constellations like Starlink are in the crosshairs

The system has drawn so much attention because it lines up with repeated warnings from Chinese officials that SpaceX and its Starlink network could pose a national security risk. Beijing’s military analysts have published several studies on how to disrupt large satellite constellations, and high-power microwaves appear frequently in that work alongside lasers and cyber tools.

Starlink satellites already play a visible role in Ukraine, where they help keep communications and drones running when ground networks fail. For Chinese planners who worry about similar systems supporting Taiwan or other flashpoints, a ground-based microwave weapon that can reach into low orbit looks like a relatively low-cost way to shut off that support.

There is also a geometric twist. Starlink has been gradually lowering the altitude of its satellites to cut collision risks and reduce space junk, a move that can make them slightly easier targets for ground-based energy beams because the distance is shorter and the signal spreads out less. What looks like a safety choice for the space environment can also change the military calculus.

What this breakthrough really means for space security

Despite the dramatic “Starlink killer” label, TPG1000Cs is still a pulsed power driver in a lab, not a fielded weapon that has zapped real satellites. To become an operational system, it would need to be integrated with a microwave source, a large directional antenna, and a platform such as a truck, ship, aircraft, or even another satellite.

Even so, independent analysts note that the new driver pushes China ahead in the race for non-kinetic anti-satellite tools that are harder to attribute than missile attacks.

Russia’s Sinus7 and other drivers reviewed by the Institute of High Current Electronics show that both Moscow and Washington have long studied similar technologies, yet the Chinese system appears to combine high power, long firing time, and compact size in a way that previous designs have not matched.

For people on the ground who depend on satellite navigation, weather forecasts, and streaming video from space, that trend means the infrastructure behind daily life is increasingly caught up in military competition.

At the end of the day, devices like TPG1000Cs underline that space is no longer just a backdrop for science missions but a contested arena where invisible beams could quietly flick off the systems we rely on.

The main study has been published in the journal High Power Laser and Particle Beams.