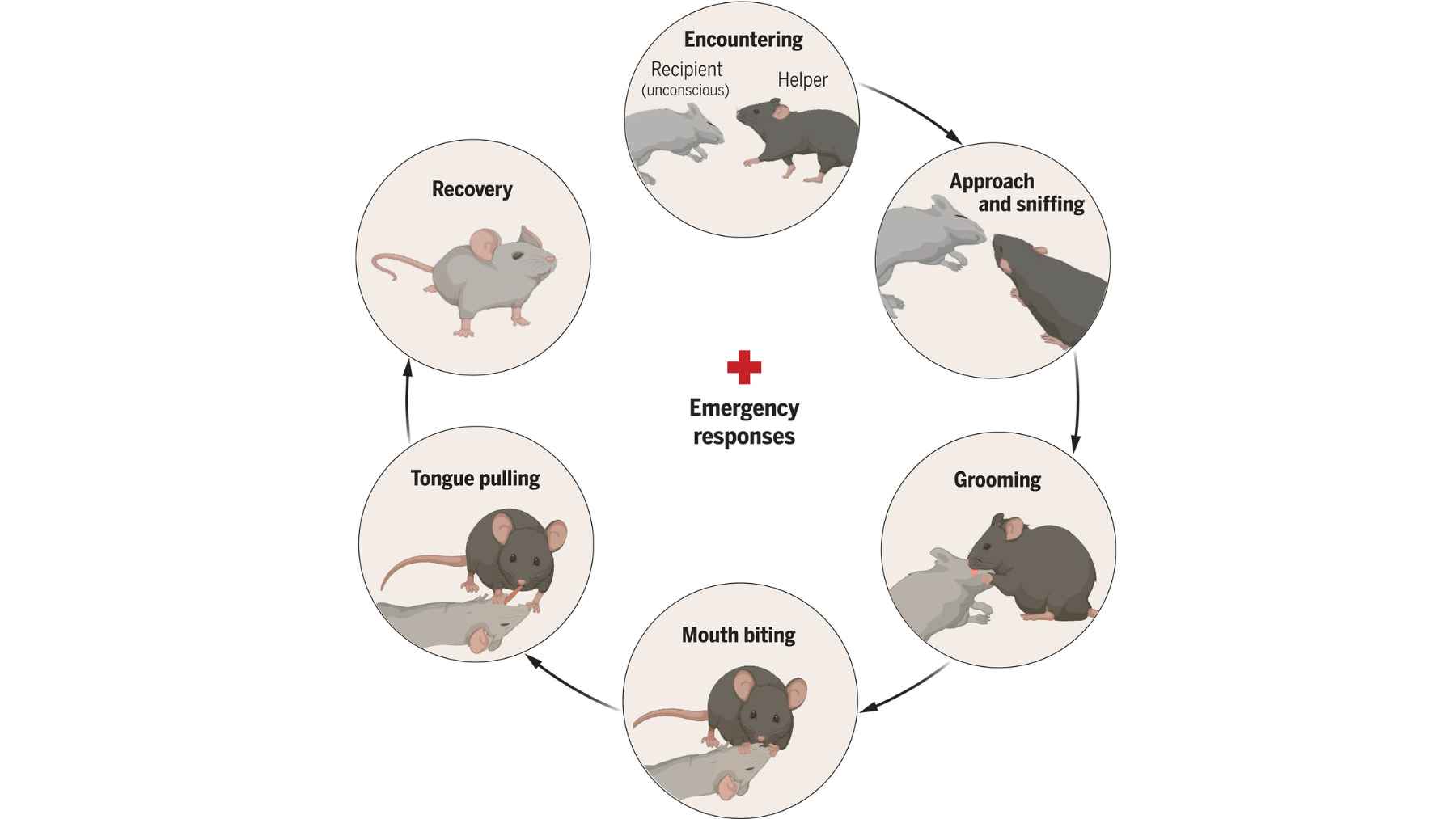

Picture a lab mouse leaning over an unmoving companion, sniffing its face, grooming its fur, then biting gently at its mouth and tugging on its tongue. It sounds like something from an animated film, yet it comes straight from high-speed lab videos and a new study in Science.

The researchers report that mice follow a surprisingly organized sequence of actions that open airways, clear obstructions and help an unconscious partner wake up faster, all while key brain circuits that use oxytocin spring into action.

Tiny first responders in the lab

The project at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California (USC) began with an accident. During routine experiments, one mouse was under anesthesia while its familiar cage mate roamed the home cage. Instead of ignoring the limp body, the awake animal rushed over and stayed there.

As Li Zhang recalls, “It all started from an accidental observation” when the team noticed how intensely the bystander mouse interacted with its unconscious partner.

To move beyond anecdotes, the scientists set up controlled tests. They placed a familiar mouse rendered unresponsive by anesthesia back into the home cage and used a machine learning system to label every movement on video.

On average, the subject mouse spent nearly half of the session interacting with the unconscious partner, compared with only a few percent when the partner was awake and moving. Most of that attention focused on the head and mouth rather than on the rest of the body.

A step-by-step rescue routine

At first, the “helper” mouse simply sniffed different body parts and groomed its partner, a kind of social checking in. When the collapsed animal stayed immobile, the behavior escalated.

The subject began to concentrate on the face, biting around the mouth, licking the head and finally clamping the loose tongue and pulling it outward. These mouth and tongue centered actions appeared in every tested mouse and became more intense over time.

Those actions had clear physical effects. When the tongue was pulled out, measurements showed that the partner’s airway opened wider than when the tongue stayed inside the mouth. In separate trials, scientists placed a small object in the unconscious mouse’s mouth.

In about 80% of cases, the bystander removed that object, something that never happened when no helper was present. Partners that received this rough care took their first steps sooner than animals left alone, which suggests the behavior genuinely helped them recover.

A closer look at the mouse brain

What tells a mouse that it is time to switch from gentle grooming to something that looks like emergency care? If you have ever seen people circle around someone who suddenly collapses on a sidewalk, you know that social context and emotion matter.

In mice, the new work traces that switch to oxytocin producing neurons in a hypothalamic region called the paraventricular nucleus. These cells fired more strongly when a familiar partner was unconscious than when it was awake. When researchers activated the oxytocin neurons with light, reviving-like actions increased. When they blocked oxytocin signaling, the behavior faded.

Another group, publishing in the same issue of Science, found that a region called the medial amygdala helps the brain recognize that another mouse is unresponsive and helps regulate the head directed contact that follows. Together, the results suggest a distributed circuit where one structure detects a partner in trouble and another helps drive the helping behavior.

Friendship, empathy and a scientific debate

The rescues were not random. Intense tongue pulling and object clearing were much more common between familiar cage mates than between strangers, and in some combinations females were more likely than males to help an unfamiliar mouse.

None of the mice had prior experience with an unconscious partner, which hints that this is an innate script rather than a learned trick.

So is this proof that mice feel empathy the way we do? Not everyone agrees. Some scientists, such as neurobiologist Peggy Mason, argue that the behavior might reflect intense investigation of a disturbing stimulus rather than a true rescue attempt, even if the outcome is helpful.

Others, including empathy researcher Inbal Ben Ami Bartal, see the work as fitting into a broader pattern of rodent helping behavior, alongside earlier studies in which rats learned to free trapped companions.

Why it matters beyond the mouse cage

For most of us, mice are pantry raiders or lab models, not tiny paramedics. Yet findings like these hint that the impulse to help an unresponsive group member may run deep across social mammals, from elephants nudging a fallen herd mate to small rodents tugging a tongue in a plastic cage.

That perspective nudges conversations about animal welfare and cognition toward a richer view of what many species are capable of feeling and doing in their everyday social lives.

The same brain circuits that push a mouse to assist a fallen friend could also help scientists understand what goes wrong in human conditions where social responses are blunted, although that link remains a long-term hope rather than a near-term application.

The study was published in Science.