Almost four hundred years ago, eight English sailors spent a winter stranded on the shores of Spitsbergen in what is now the Norwegian Arctic. Their story is one of hunger, polar bears and brick walls built in the dark.

Today, the same coastline is becoming one of the fastest warming places on the planet. The ice that once nearly killed them is now melting at record speed.

In 1630, a small whaling fleet from the English Muscovy Company reached the waters off Spitsbergen, the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago. One of the ships, the Salutation, sent eight men ashore in a small open boat to hunt reindeer. They expected to be gone for a few days at most.

Bad weather pushed the main ship away from the coast. With no navigation tools and very limited food, the hunting party tried to reunite with the fleet and missed it by a matter of hours. When the whaling ships finally left for England, the eight sailors were still on Spitsbergen, alone in the High Arctic and facing nine months of darkness.

Their names survive thanks to the account of Edward Pellham, a gunner’s mate who later wrote a long pamphlet about what happened. The men camped near an abandoned 17th-century whaling station, tore down the old brick ovens that had once rendered whale blubber into oil, and rebuilt the bricks into a smaller house tucked inside a larger wooden frame.

That double shell gave them a kind of crude insulation, the 17th-century version of an Arctic survival shelter.

Whaling stations, polar bears and life on the edge

The same whaling boom that brought the sailors there had already transformed these fjords. From the early 1600s, English and Dutch companies built seasonal camps around Svalbard to chase bowhead whales, boiling blubber in huge brick furnaces to supply oil for lamps back in Europe.

Archaeologists who excavate those sites today see them as early examples of intensive industrial use of a fragile polar ecosystem.

For the stranded crew, that history became a lifeline. They burned leftover timbers from wrecks and empty barrels, scavenged scraps of whale fat from old dumps and even made crude lamps to soften the crushing polar night.

They rationed food until they were eating only once per day and added regular fasts. When polar bears began to visit, the animals were both a terrifying threat and a vital source of meat. Pellham recalls that after eating bear liver the men became seriously ill, a reminder that Arctic species often carry toxins humans are not adapted to handle.

In the end, they killed several bears, along with reindeer and Arctic foxes, and made it to spring. Against the odds, all eight survived until whaling ships from Hull arrived the following summer and took them home. Their winter was a brutal crash course in Arctic ecology long before that phrase existed.

From frozen fortress to warming hotspot

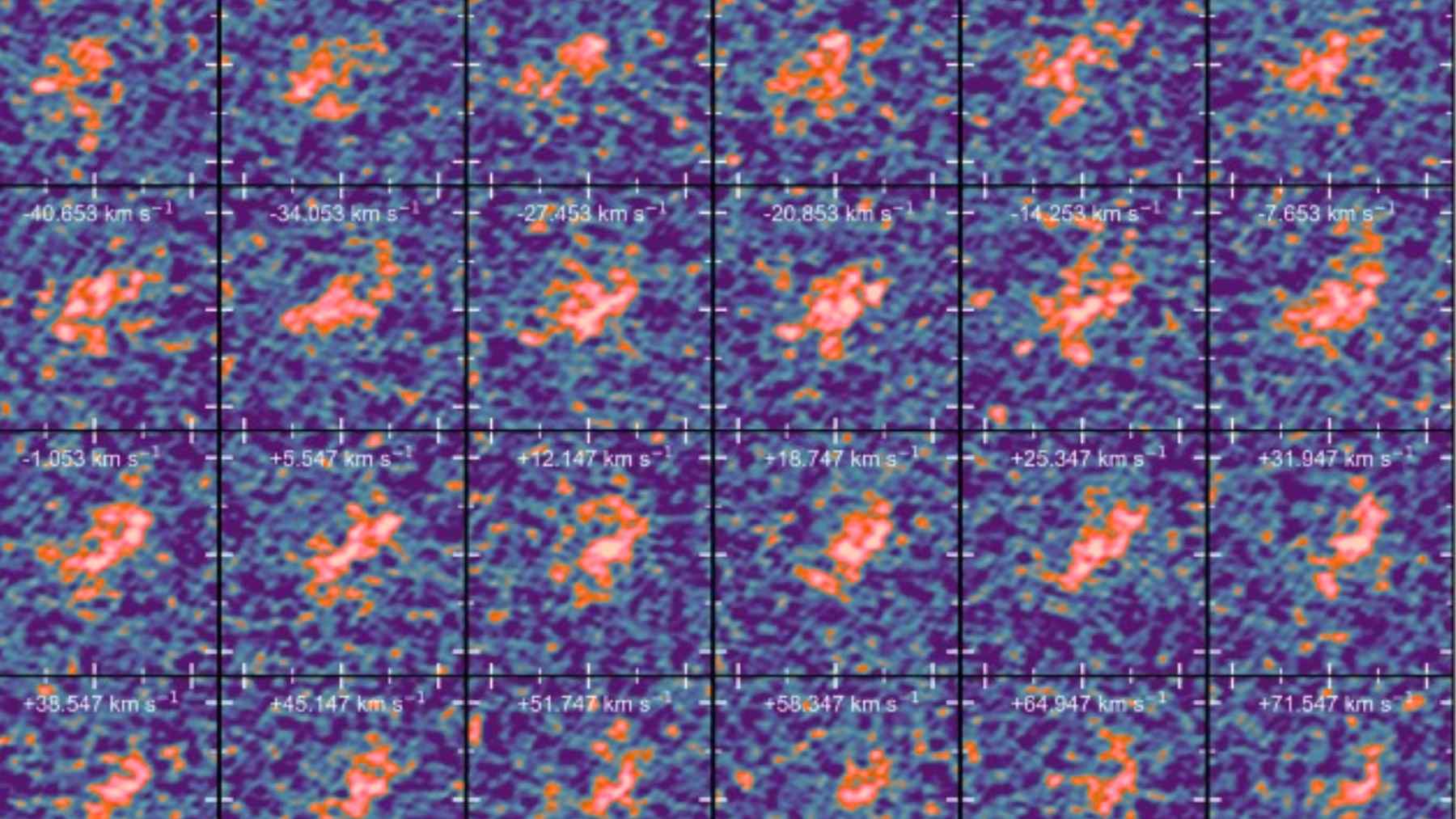

If those sailors could step onto Spitsbergen today, the landscape would still be harsh, but the climate would not be the same one that nearly froze them. Modern satellite records show that, since the late 1970s, the Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average.

Some parts of Svalbard are changing even more quickly. Recent research suggests this region has warmed around six to seven times faster than the planet as a whole since the late 1970s, especially in winter. Snow arrives later, rain falls more often on top of existing snow, and sea ice near shore is thinner and less reliable.

According to the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the latest Arctic Report Card shows that surface air temperatures from late 2024 to late 2025 were the warmest in at least a century of records, while winter sea ice reached new lows.

Scientists describe rivers running orange as thawing permafrost releases sediments and metals, and they document rapid shifts in plant growth and animal habitats.

For people who live and work in the Arctic today, that means less predictable travel over ice, more dangerous storms and a growing risk that the world the whalers knew will exist only in archives and archaeological digs.

For everyone else, it means stronger feedbacks into the global climate, from rising sea levels to altered weather patterns that can influence the heat waves and storms showing up on our own electric bills.

A race to protect ice and memory

The ruins that sheltered Pellham and his companions are now considered cultural heritage. Researchers such as Norwegian archaeologist Alma Elizabeth Thuestad have used tools like satellite data and drones to track how rising temperatures, thawing permafrost and stronger storms are eroding whaling stations around Svalbard.

In practical terms, this means more brick walls collapsing, more wooden beams rotting and more artifacts washing out to sea. The same climate trends that threaten polar bears and sea ice are also eating away at the physical record of how humans first exploited and then tried to survive in the region.

So this old survival story is not only a tale of courage. It is also an early chapter in a much longer history that now includes rapid warming driven by fossil fuels.

At the end of the day, those eight sailors remind us how unforgiving the Arctic can be, even as modern data warn that the real danger now is losing the frozen world they fought so hard to endure.

The report was published in the Arctic Report Card 2025.