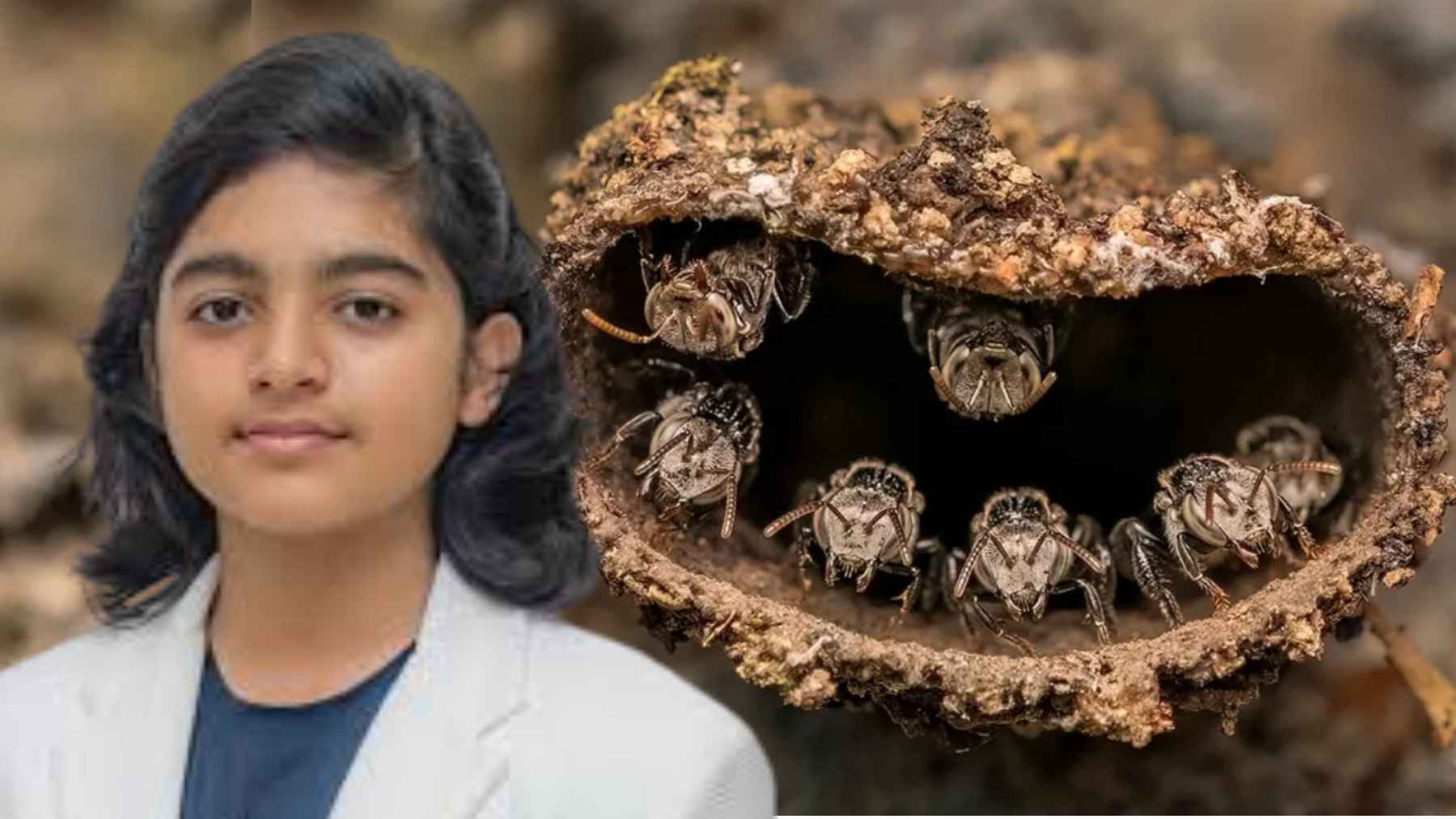

Young wildlife photographer Rithved Girish has been named Young Close‑up Photographer of the Year 7 for his image “Guardians of the Hive,” winning the youth category of the international Close‑up Photographer of the Year competition.

The photo captures stingless bees on guard at the entrance of their nest in Mezhathur, Kerala, and it does more than dazzle judges; it quietly tells a story about how much we depend on insects most of us never notice.

Hidden wildlife, simple gear

Rithved lives in the United Arab Emirates but returns regularly to India, where he spends his school breaks exploring farms, backyards, and patches of semi‑wild land. On one of those summer visits to Kerala, he spotted a nest belonging to tiny stingless bees, likely from the Tetragonula family, building a narrow mud‑and‑resin tube that works like a front door and fortress in one.

Instead of baiting or disturbing the nest, he waited. The result is a close‑up of “guard” bees at the entrance, their bodies forming a living shield around the tube as they watch for threats. The scene turns a piece of old wall into something that looks almost like architecture or sculpture, but it is pure natural behavior unfolding in real time.

His winning picture is striking for another reason too. He did not use a brand‑new mirrorless camera or exotic custom lens. The image was made with a nearly decade‑old Nikon D850 DSLR, paired with a third‑party macro lens designed to reveal fine details in very small subjects.

In other words, no latest‑generation mirrorless body, no futuristic gadget stack. In practical terms, that means the heavy lifting came from fieldcraft and patience rather than a shopping spree at the camera store.

A competition built on tiny details

Close‑up Photographer of the Year has grown into the world’s largest contest dedicated to macro and close‑up photography, attracting more than twelve thousand entries from sixty‑three countries. Its categories celebrate everything from insects and spiders to underwater scenes, plants, fungi, and even studio experiments with everyday objects.

A jury of twenty‑two photographers, naturalists, and editors chose the top images and the overall winners. That kind of panel matters because these experts are not just looking for pretty colors; they look for technical skill, storytelling, and a sense that the photographer understands the subject’s behavior and context.

In that sense, “Guardians of the Hive” fits right into a larger conversation about how we see small life on a crowded planet. It is not just an impressive close‑up; it is a reminder that even the smallest colonies are busy doing quiet work that keeps ecosystems running.

What stingless bees are doing for the planet

Stingless bees belong to a group of tropical and subtropical pollinators that rarely make headlines, partly because they are so small and lack the dramatic sting associated with honey bees.

Yet scientists consider them vital pollinators for many wild plants and tropical crops, especially in regions like India, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.

Research in recent years has shown that stingless bee species such as Tetragonula iridipennis can boost yields in greenhouse crops and orchards, often without the safety concerns that come with keeping large honey bee colonies in densely populated areas.

Farmers who work with these tiny bees report better fruit set and quality in crops ranging from chilies and tomatoes to some spices and oilseeds.

At the same time, stingless bee populations face familiar pressures from habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate stress. Because they nest in tree cavities, old walls, and other sheltered gaps, their colonies disappear quickly when landscapes are cleared or heavily paved over.

For a teenager to spotlight their world at exactly this moment gives their story a wider audience than most scientific papers ever reach.

Pollinators, food, and everyday choices

More than three‑quarters of global food crops benefit in some way from insect pollination, yet many pollinator groups are thought to be in decline. Fruits, nuts, seeds, and even the oils used in everyday cooking all depend on busy insect traffic between blossoms.

When those insects vanish, yields drop and quality can suffer. Farmers may turn to hand pollination or mechanical substitutes, which are costly and rarely as efficient. For people far from farm fields, the impact shows up quietly as higher prices, fewer varieties on supermarket shelves, or a slow shift toward calorie‑rich but nutrient‑poor staples.

It is easy to treat pollinator decline as something abstract that happens “somewhere else.” Images like Rithved’s cut through that distance. They put a face, or in this case many tiny faces, on the animals that keep food systems resilient.

Photography as a bridge between science and daily life

Nature photography competitions have long played a role in shaping how the public thinks about conservation. A single powerful frame can spark curiosity in a way charts and reports rarely do.

For young viewers, seeing someone their own age recognized at a global level sends another message too. You do not need a lab coat to contribute to environmental awareness; a camera, a curious eye, and respect for your subject are a strong start.

Close‑up contests also reward the habits that scientists rely on every day: noticing small details, returning to the same spot at different times, and patiently waiting for behavior to unfold. In that sense, a teenager working a macro lens in the heat of a Kerala afternoon is not so different from a field biologist collecting data on pollinators in orchards or forest edges.

The technical side of the image matters less to most viewers than the story it tells, but there is still a quiet lesson in the gear choice. Using a ten‑year‑old professional body with a third‑party lens shows that high‑impact environmental storytelling is not locked behind the latest expensive camera release.

For families worried about budgets or young people borrowing a parent’s DSLR, that message can feel surprisingly liberating.

A small nest with a big message

In the end, “Guardians of the Hive” is unforgettable because it shrinks the stage. There are no sweeping landscapes, no dramatic sunsets, just a few centimeters of mud tube and a cluster of insects that many people would walk past without a second glance.

The photograph turns that tiny scene into something as compelling as any wildlife encounter on a safari.

It also lands at a time when scientists are warning that pollinator declines could ripple through food systems and ecosystems for decades.

That makes every new story about bees, butterflies, and other insect partners a chance to nudge behavior a little, whether that means planting a small patch of native flowers on a balcony or supporting farms that cut back on harmful pesticides.

At the end of the day, that is what this contest celebrates: slowing down long enough to really see the living systems that feed us. A fourteen‑year‑old’s patience in front of a stingless bee nest reminds us that the world is full of “hidden wonders,” and that paying attention to them is one of the simplest climate and conservation actions any of us can take.

The official winners gallery and caption were published on the Close‑up Photographer of the Year.