What would you do with a machine that makes gravity nearly two thousand times stronger than what you feel right now at your desk? In China, engineers have just brought that idea to life with CHIEF1900, the most powerful hypergravity centrifuge ever built.

By spinning heavy samples in a huge underground rotor, the machine lets scientists speed up slow physical processes that would normally take decades or even thousands of years. That way, they can watch a model dam crack, a rail bed shake, or pollution creep through soil in just days instead of lifetimes.

What this hypergravity machine actually is

CHIEF1900 is a hypergravity centrifuge, a giant spinning arm that can load multi-ton models or samples and whirl them at extreme speed. It is installed in the national Centrifugal Hypergravity and Interdisciplinary Experiment Facility, a lab built beneath the campus of Zhejiang University about fifteen meters below ground to keep vibrations under control.

Hypergravity simply means gravity stronger than the normal pull you feel at Earth’s surface, which scientists call 1 g. In CHIEF1900, the combination of load and spin can reach up to 1,900 g tons, a measure that multiplies the strength of gravity by the mass being tested.

The project is led by geotechnical engineer Chen Yunmin, a fellow of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In university briefings, he describes hypergravity as a way to compress space and time in the lab by recreating huge natural systems at model scale. In his words, this kind of setup gives researchers an opportunity to discover completely new phenomena and even new theories.

How CHIEF1900 “compresses” time

At its core, the machine works a lot like a supercharged version of the spin cycle in a washing machine. When a model fixed to the spinning arm moves in a tight circle, it feels an outward pull that mimics very strong gravity. By dialing up that pull, scientists can make a one-meter model behave the way a hundred-meter structure would behave in the real world.

One early example uses a three-meter model of a three-hundred meter dam, spun at around 100 g to reproduce the stress that a real megastructure would feel in service. In the centrifuge, sensors can track tiny cracks, shifting joints, or zones where the model starts to sag long before a full-size version would ever be built.

For engineers, it is like watching a time lapse of a future failure play out safely inside concrete walls.

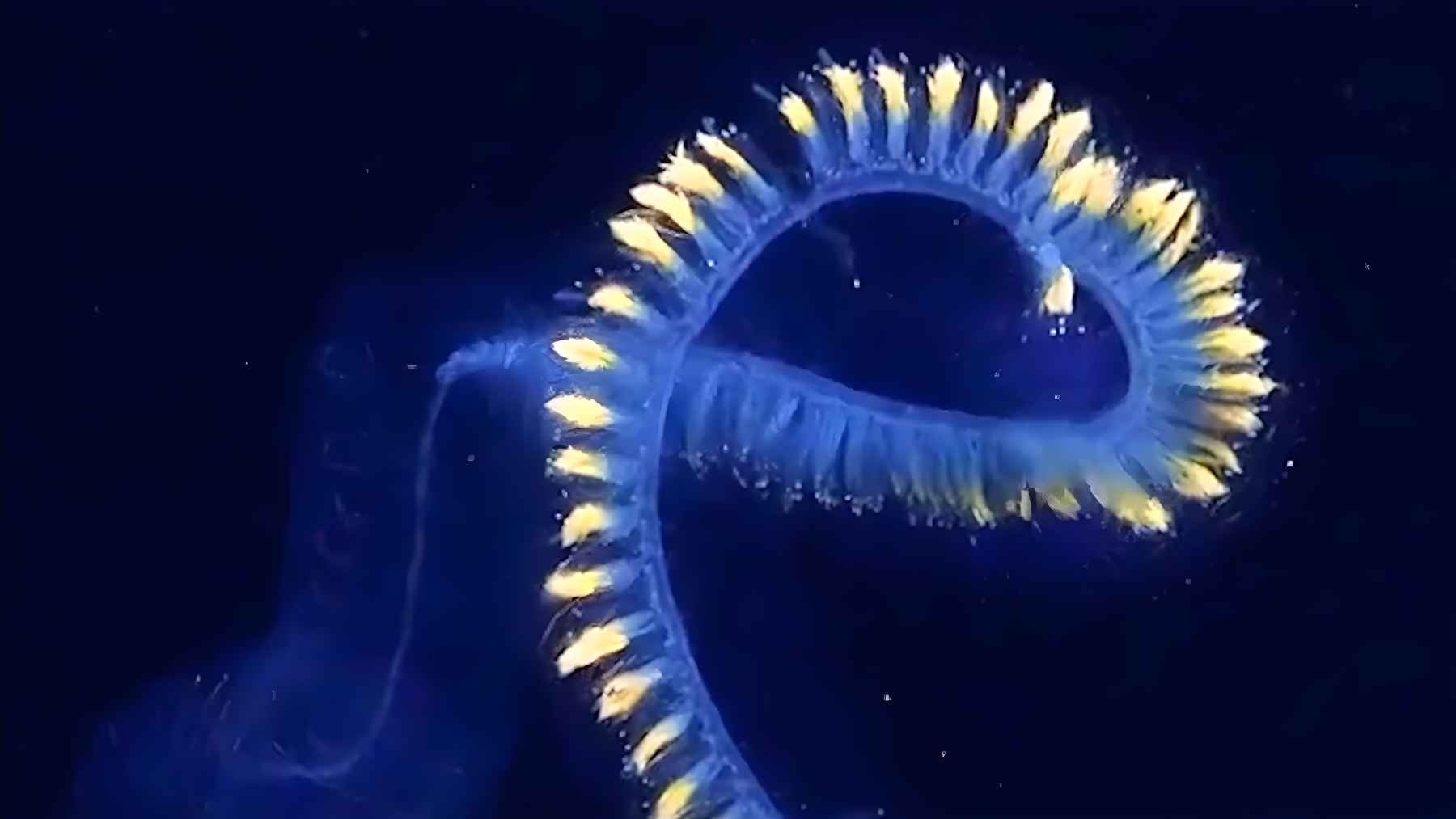

The same trick lets researchers follow very slow processes such as how pollutants migrate through layers of soil into groundwater. Under everyday gravity, that journey might take hundreds or even tens of thousands of years, far longer than any lab project or environmental permit.

In a hypergravity field, the same plume can cross the model in a few days, giving regulators and cleanup teams hard data instead of guesses.

From giant dams to high-speed rail

Designing and checking huge dams is an obvious use, given how much damage a failure can cause downstream.

The CHIEF team also lists steep slopes, tunnels, and earthquake resistant foundations among its main targets, since all of them involve complex interactions between soil, rock, and concrete. In practical terms, that means stress tests on models of mountain highways, metro lines, and coastal defenses that would be impossible to run full size.

Another focus is transportation infrastructure, especially high-speed rail tracks that must stay stable and quiet even after millions of train passages. By spinning realistic sections of track and ground at hypergravity levels, engineers can see how vibration builds up, how ballast settles, and where maintenance crews might face trouble years down the road. Anyone who has tried to sleep on a noisy overnight train knows why small improvements here can make life better.

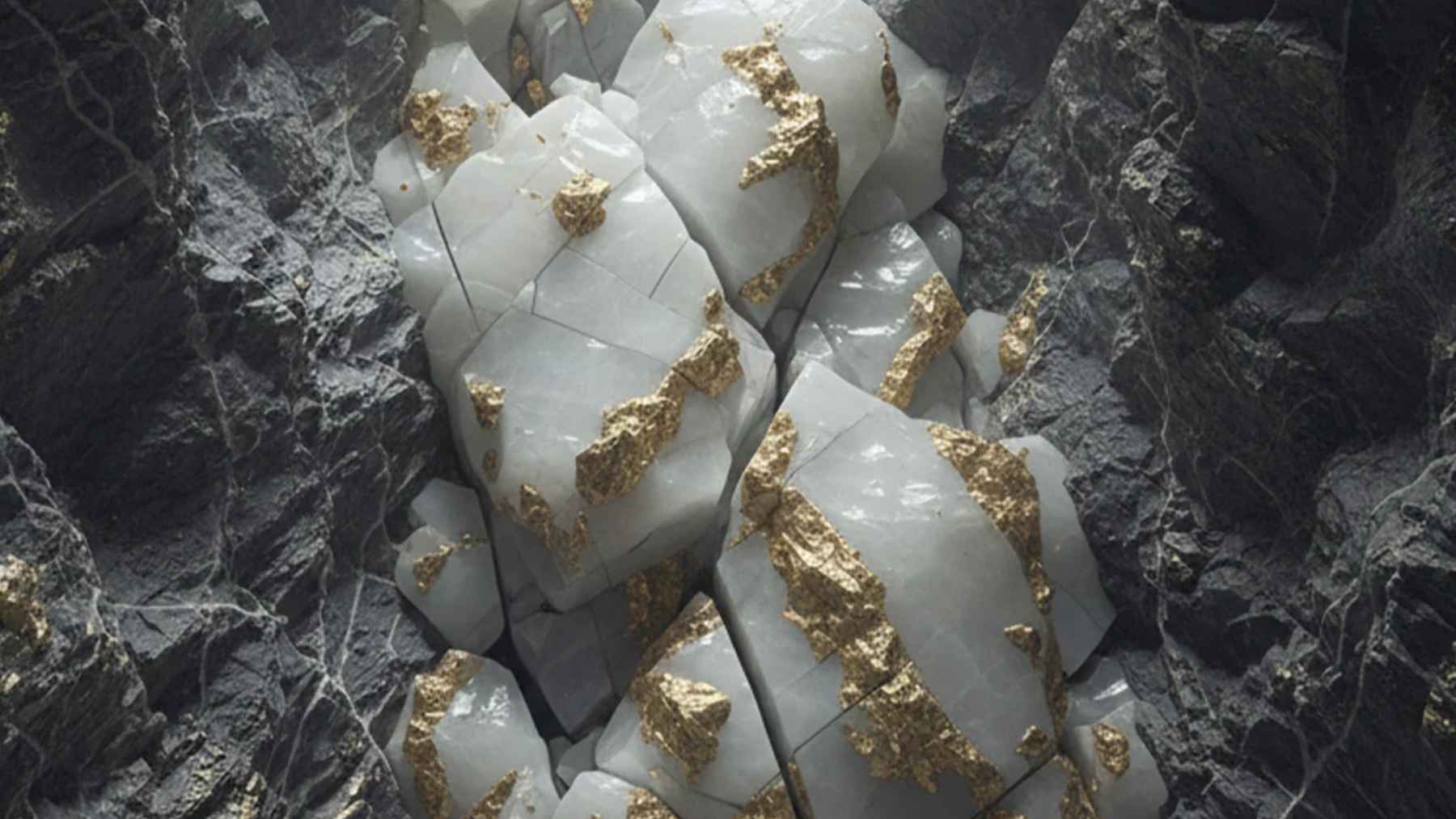

The facility is also designed for deep-sea and deep-earth studies, including work on natural gas hydrates and underground waste storage. Under hypergravity, the separation of fluids and solids speeds up, which helps scientists understand how buried contaminants spread and how new materials behave under intense pressure.

It may not fix a leaky landfill on its own, but better models from this machine could help keep future drinking water and farmland safer.

A new benchmark in the hypergravity race

For years, the reference point in this field was a large centrifuge operated by the US Army Corps of Engineers in Vicksburg. That machine can reach roughly 1,200 g tons, and for a long time it set the global bar for heavy-duty centrifuge research. Now CHIEF1900 and its slightly smaller sibling CHIEF1300 move that bar sharply higher.

Public plans describe three main centrifuges and multiple experimental cabins in the Chinese facility, each tuned to different types of tests from seismic geotechnics to materials science.

The hypergravity lab in Hangzhou is meant to operate as a shared platform where domestic and international teams can book time much like researchers do at big telescopes or particle accelerators. According to coverage in the South China Morning Post and other outlets, local authorities see its completion as a milestone in hypergravity research.

For the most part, no one knows yet exactly how much this new power will cut real-world risk or cost. That will depend on how openly data are shared, which projects get priority, and whether regulators trust centrifuge results enough to change codes. What is clear already is that the race to build stronger and more flexible hypergravity machines has moved up a gear, and that scientists now have a remarkable new tool to probe how our planet behaves over very long timescales.