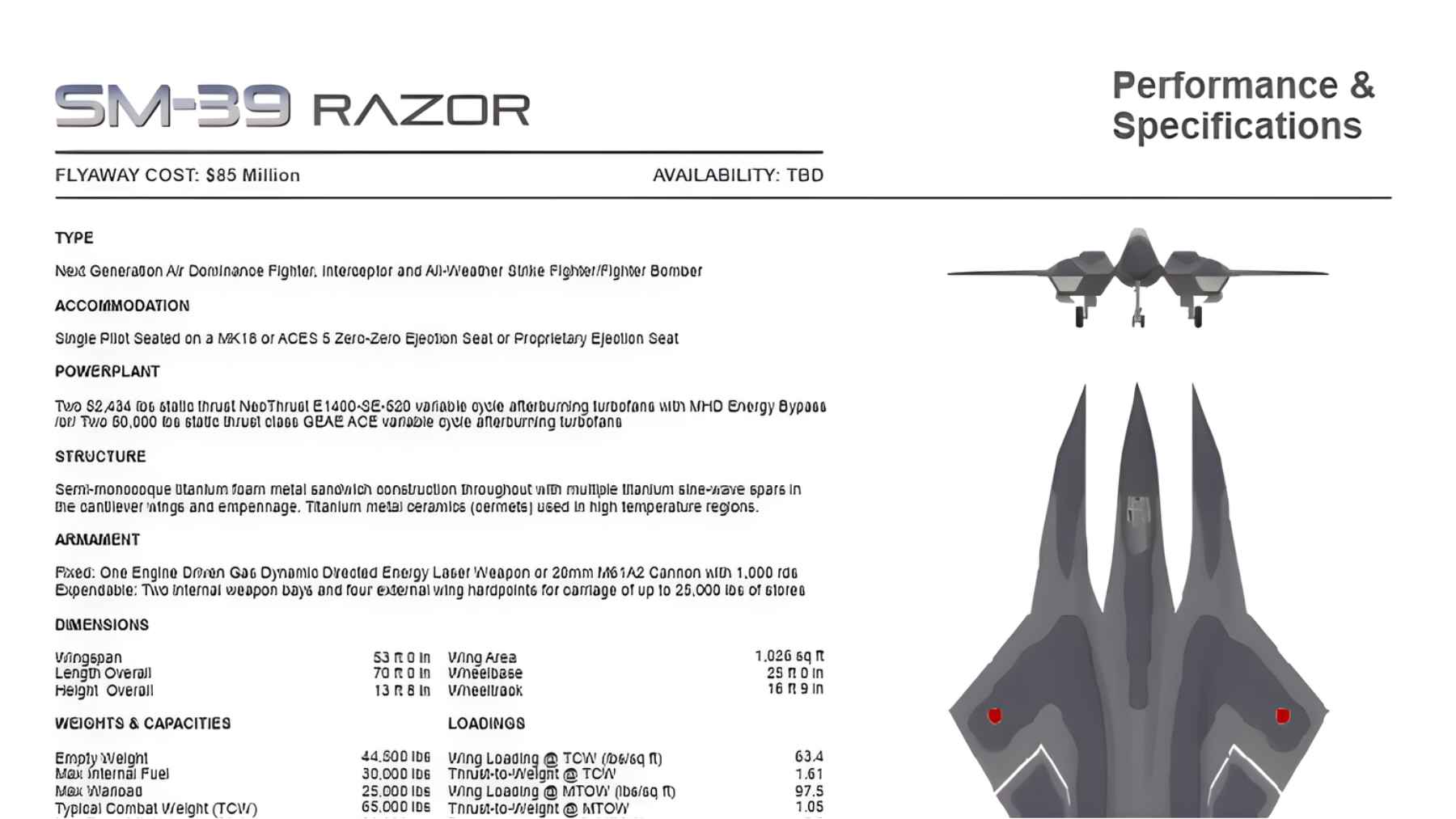

The idea sounds like science fiction at first glance. A small American firm, Stavatti Aerospace, is pitching a “bat wing” combat jet called the SM 39 Razor to the United States Navy. On paper, this carrier-based fighter would sprint to around four times the speed of sound and supercruise far above Mach 2 while staying stealthy and heavily armed.

Radical aircraft design and advanced jet engines

The concept stands out for its radical shape. Company material and recent coverage describe a triple fuselage blended into a wide, curved wing, designed to cut supersonic drag while hiding weapons inside large internal bays.

Stavatti talks about next generation adaptive cycle turbofan engines, long range and a unit price similar to today’s advanced fourth generation jets. Yet the official F A XX competition still centers on proposals from Boeing and Northrop Grumman, and the Navy has not confirmed that the Razor is even a formal contender.

Engineers are cautious for several reasons. Analysts quoted in recent reports question whether a carrier fighter built around turbofan engines can really sustain Mach 4 without running into crushing thermal loads and airflow problems.

At those speeds, skin temperatures could reach several hundred degrees Celsius, which would punish any stealth coating and turn the aircraft into a bright infrared target. On top of that, Stavatti has existed since the mid-1990s but has not yet flown a full-scale prototype of any design, and public data show a very small team and revenue base.

Supersonic aviation climate impact and CO2 emissions

So why should an environmental outlet care about a paper fighter that may never leave the drawing board? Because the Razor points toward a familiar temptation in aviation. Whenever designers chase extreme speed and altitude, fuel burn and climate impacts tend to climb as well. Global studies for civil supersonic projects suggest future high-speed fleets could use roughly

three to nine times more fuel per passenger kilometer than modern subsonic airliners and would inject nitrogen oxides and water vapor into the lower stratosphere, where they can disturb ozone and trap heat.

One recent analysis found that even moderately fast Mach 1.6 and Mach 2.2 concepts would change global ozone by up to about one percent and create non-CO2 climate effects that rival or exceed the warming from their carbon dioxide emissions. The authors also showed that using low-sulfur fuels can reduce ozone depletion but may increase overall warming by removing a small cooling effect from sulfate particles. In other words, there is no simple technical fix that makes very fast jets climate neutral.

Military aviation emissions and environmental responsibility

Military aviation sits inside an even more uncomfortable picture. Research from Brown University’s Costs of War project and others concludes that the United States Department of Defense is the largest institutional consumer of fossil fuels on the planet and a major greenhouse gas emitter, with jet fuel for fighters and bombers making up a large share of that footprint.

A Mach 4 carrier fighter would almost certainly burn more fuel per hour than today’s jets, concentrate emissions at higher altitudes and add intense noise and sonic boom impacts to already stressed oceans and coastlines.

For the most part, projects like the SM 39 remain vision pieces rather than operational hardware. Yet they signal how easily new defense programs can lock in another generation of carbon-intensive equipment at the very moment when every sector is under pressure to cut emissions.

As climate risks grow, pressure is likely to increase on navies and air forces to apply the same scrutiny to “exotic” high-speed designs that civil regulators are already turning on commercial supersonic dreams.

The scientific assessment was published on ICAO.