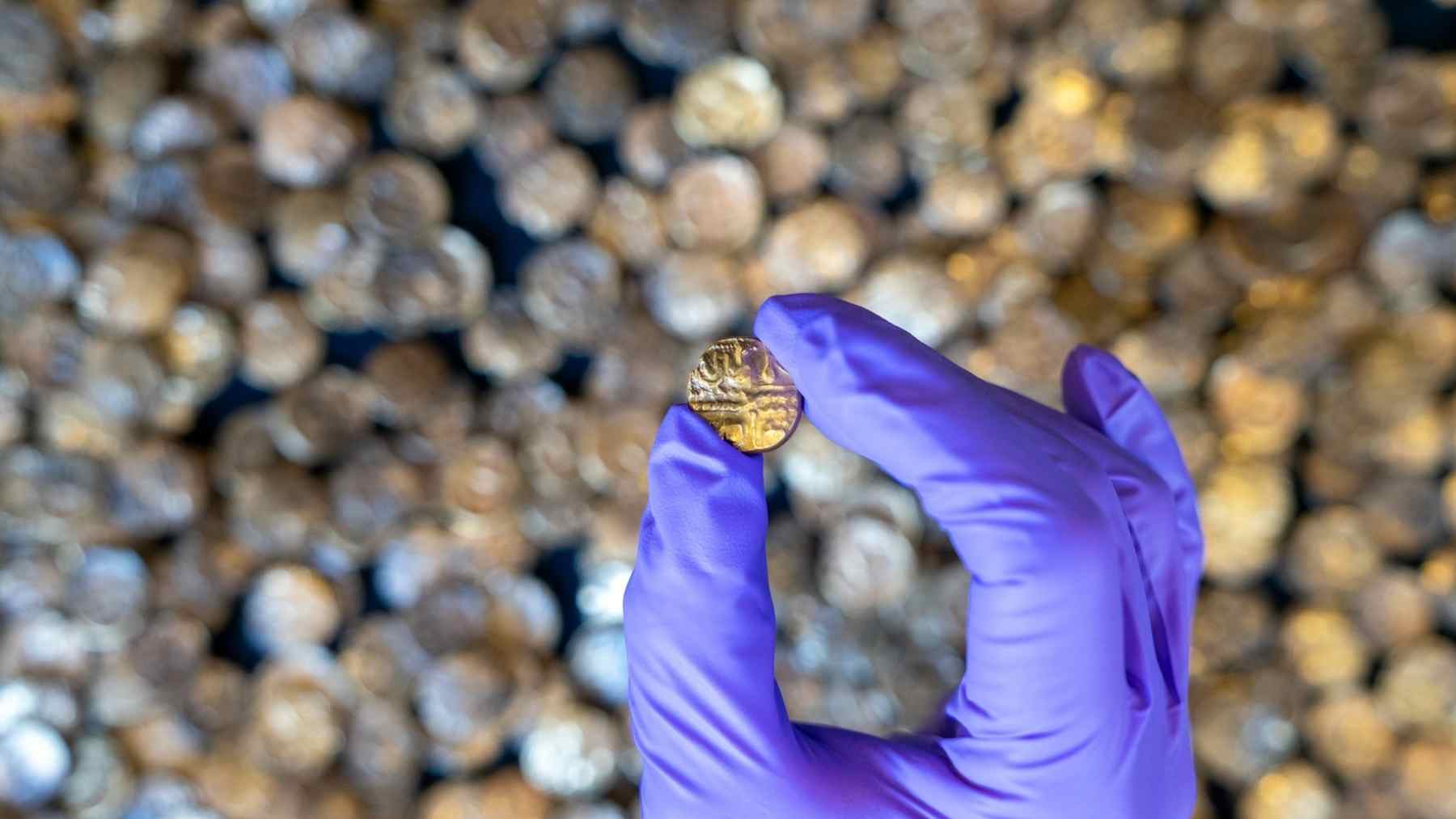

A metal detectorist working near Great Baddow in Essex uncovered a stash of 933 gold coins dating to roughly 60 to 20 BC, a find now known as the Great Baddow Hoard. Officials say it is the largest recorded hoard of Iron Age gold coins ever found in Britain, and it is already reshaping what historians can say about power and money right before Rome tightened its grip on southern Britain.

What makes it unusual is not just the number of coins, but what they represent. These were minted by local tribes, meaning they are direct evidence of decisions made by leaders and communities during a tense and fast-changing period.

A jackpot of coins that freezes a moment in time

A hoard this large is like a snapshot, not a scrapbook. Instead of a few scattered finds over decades, you get a concentrated pile of money from one place, buried at one moment, and never retrieved. That can point to urgent movement, planned storage, or a transfer of wealth that suddenly became too risky to complete.

Chelmsford City Council’s Jennie Lardge said the discovery helps fill gaps in what is known about the area’s Iron Age past, which is thin compared with later Roman layers. One cache can do that, especially when it is big enough to show patterns rather than one-off accidents.

Coins that echo a political power struggle

The hoard’s location matters as much as its size. Museum of Chelmsford curator Claire Willetts said most of the coins are thought to have been produced in a region later linked to the group often called the Catuvellauni, yet they were found in territory traditionally associated with the Trinovantes.

That mismatch hints at movement and influence pushing east, and possibly conflict, around the same era when Julius Caesar described hostages, tribute, and shifting alliances in Gallic War Book V. Coins do not tell stories by themselves, but when you map them against landscapes and written accounts, they can start to sound a lot like evidence.

What a stater is and why the design matters

Most of the hoard is made up of staters, small gold coins used as high-value currency, the kind of money tied to status and serious transactions. In simple terms, this was not spare change you lose in the couch. It was wealth meant to pay warriors, reward loyalty, or signal who had the authority to issue money at all.

The press release says 930 of the coins are “Whaddon Chase” type staters, a recognizable regional style. A reference point for that style can be seen in the British Museum collection, where the abstract patterns and stylized horse show how local mints created a shared visual language that still lets experts trace influence today.

The legal lesson behind the headlines

The hoard also comes with a warning label for modern life. Officials say it was found on private land in 2020 and was not reported promptly, which limited what could be learned about its exact burial context.

Under the Treasure Act 1996, finds believed to be treasure must be reported, and government guidance also stresses reporting within 14 days through the proper channels. That system relies heavily on the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which records publicly found objects so the history is not lost even when artifacts move into museums or private hands.

From field to display case and what happens next

The Museum of Chelmsford acquired the hoard in May 2025 after support that included a major grant and additional local contributions. The National Lottery Heritage Fund’s published decisions list an award of £249,183 for a project designed to secure and display the collection, alongside community engagement work.

The museum plans a dedicated exhibition in summer 2026, followed by a permanent display in spring 2027. That timeline gives curators room to study tiny differences in coin designs and to explain, in plain language, what this money says about fear, power, and identity in late Iron Age Britain.

The official press release was published on City Life.

Image credit: Fountains Media.