About 1,500 years ago, someone in what is now southeastern Norway walked up to a rocky slope carrying seven glittering gold pendants. Instead of wearing them, they buried them in the clay, most likely as a sacrifice meant for the gods rather than for human eyes.

Those same pendants have now been recovered near the municipality of Råde in Østfold County. A metal detector enthusiast first uncovered four pieces in a plowed field, and archaeologists from the University of Oslo later found three more during a follow up excavation. Researchers date the hoard to the sixth century, several hundred years before the Viking Age, and see it as a rare high status offering.

Seven bracteates for the gods

The gold discs belong to a special class of jewelry known as bracteates. These are thin, one sided pendants made from very pure gold. Around 900 bracteates are known worldwide, with about 160 found in Norway, so discovering seven in one spot is no everyday find for archaeologists.

On the new pieces, the familiar portrait of a Roman emperor has been replaced with Norse imagery. Riders with flowing hair, horse-like animals, birds, and tightly coiled beasts fill the tiny surfaces. Researchers classify the Råde hoard as a mix of C type and D type bracteates, which helps place the burial in the sixth century.

According to archaeologists at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, there is “little doubt that these were items connected to aristocratic communities within a Germanic elite in Scandinavia,” and the pendants likely acted as visible symbols of status and alliances. Only people with considerable wealth could afford to bury so much high purity gold in the ground and walk away from it.

Rituals in a restless landscape

The pendants date to what historians call the Migration Period, a time between the fourth and sixth centuries marked by shifting borders, alliances, and trade routes. It was also a period of environmental upheaval.

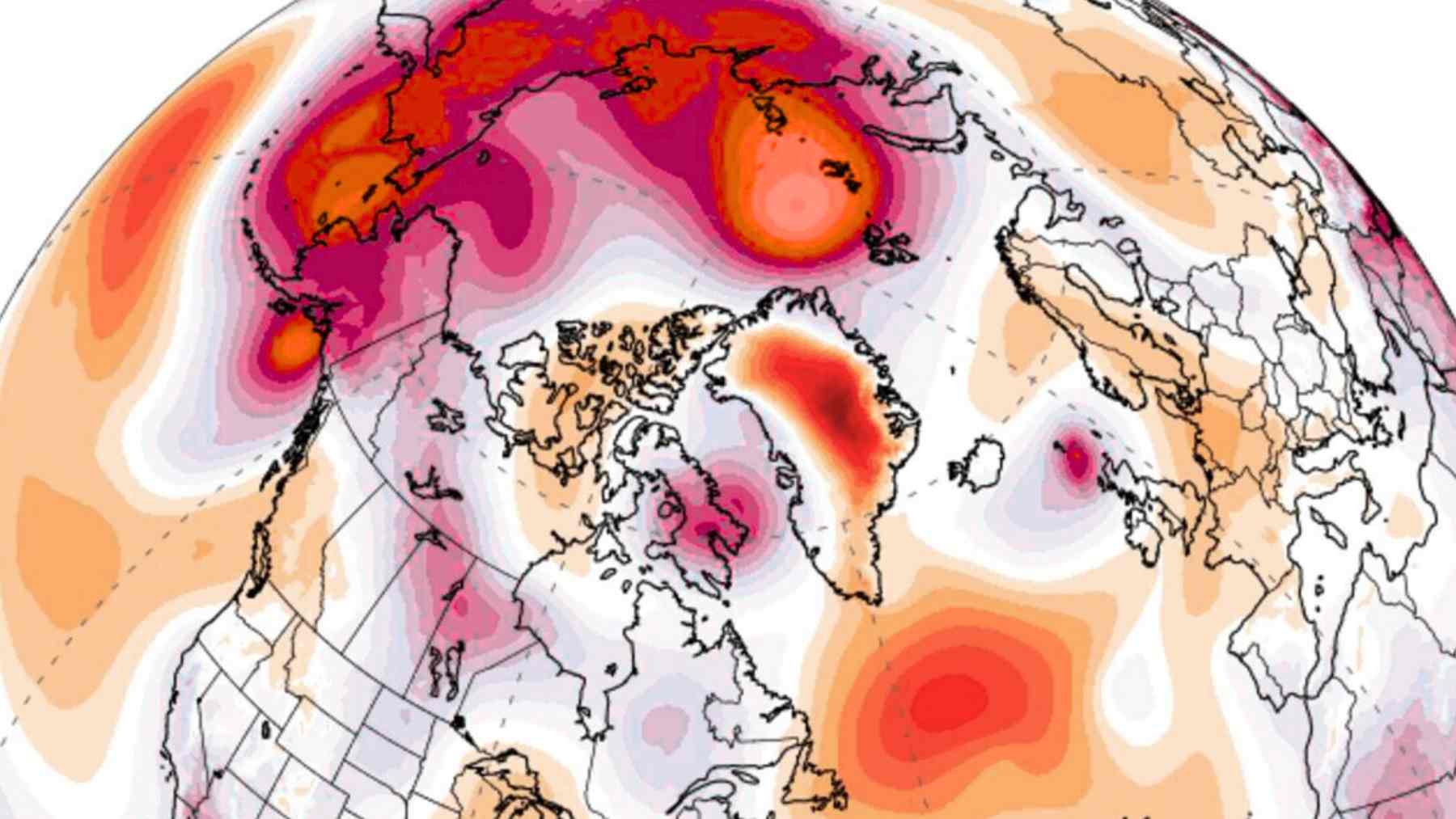

Tree ring records and glacial data point to a sharp cooling after a series of volcanic eruptions in the years 536 and 540. A study in Scientific Reports links those eruptions to a veil of volcanic dust that dimmed sunlight, reduced plant growth, and “threatened food security over a multitude of years” for societies across the Northern Hemisphere.

Later Norse stories remembered a legendary Fimbul winter, a long season of darkness and hunger. Archaeologists note that many Scandinavian gold offerings, including bracteate hoards, cluster in this troubled century and suggest that in years of poor harvests and uncertainty, elites may have felt a stronger need to seek protection by giving up their most valuable ornaments.

Seen in that light, the Råde pendants become more than beautiful jewelry. They start to look like a response to a climate crisis, a way for powerful families to negotiate with unseen forces when the weather turned strange and fields did not reliably feed their households.

Tiny amulets, big questions

Today the seven bracteates are being conserved and studied at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo. Some are slightly bent, and parts of the motifs are hidden. Researchers are using advanced imaging, including scanning electron microscopes, to examine tool marks and microscopic scratches on the gold surfaces and to compare them with other finds across Scandinavia.

In practical terms, this means that a single field in Østfold can reveal how far stories, fashions, and ritual practices once traveled across northern Europe. Similar bracteate hoards are still being found in Norway, reminding researchers that the landscape is far from finished giving up its secrets.

These treasures may feel far removed from everyday concerns like rising power bills or today’s erratic weather, yet they show that people have been living through environmental shocks and trying to make sense of them for a very long time.

At the end of the day, the Råde hoard invites a simple question. When the world around you seems less predictable, what are you willing to give up in order to feel that someone is listening?