India is electrifying its economy faster than China did at a similar stage of development, and it is doing so with far less coal burned per person. According to a new report from energy think tank Ember, India is building its industrial future on cheap clean electricity instead of following the fossil-fuel-heavy path taken by China and Western economies.

In simple terms, that means more factories, homes, and vehicles plugging into cleaner power rather than relying on oil and coal. If this “electrotech shortcut” works, it could give other developing countries a way to grow their economies without locking in decades of coal smoke and volatile fuel bills.

A new electrification shortcut for India

Electrification is the share of a country’s energy use that runs on electricity instead of burning fuels directly. Ember’s analysis finds that India’s economy is now almost 20% electrified, a level similar to China around 2012, and that share has been rising by roughly five percentage points per decade.

What does that mean in everyday life? It means more machines on factory floors, more trains, and more home appliances powered by the grid instead of diesel generators or small coal boilers. When Ember compares India today with China at the same income level, it finds India using less fossil fuel per person, backed by rapid growth in solar power, electric vehicles, and battery storage.

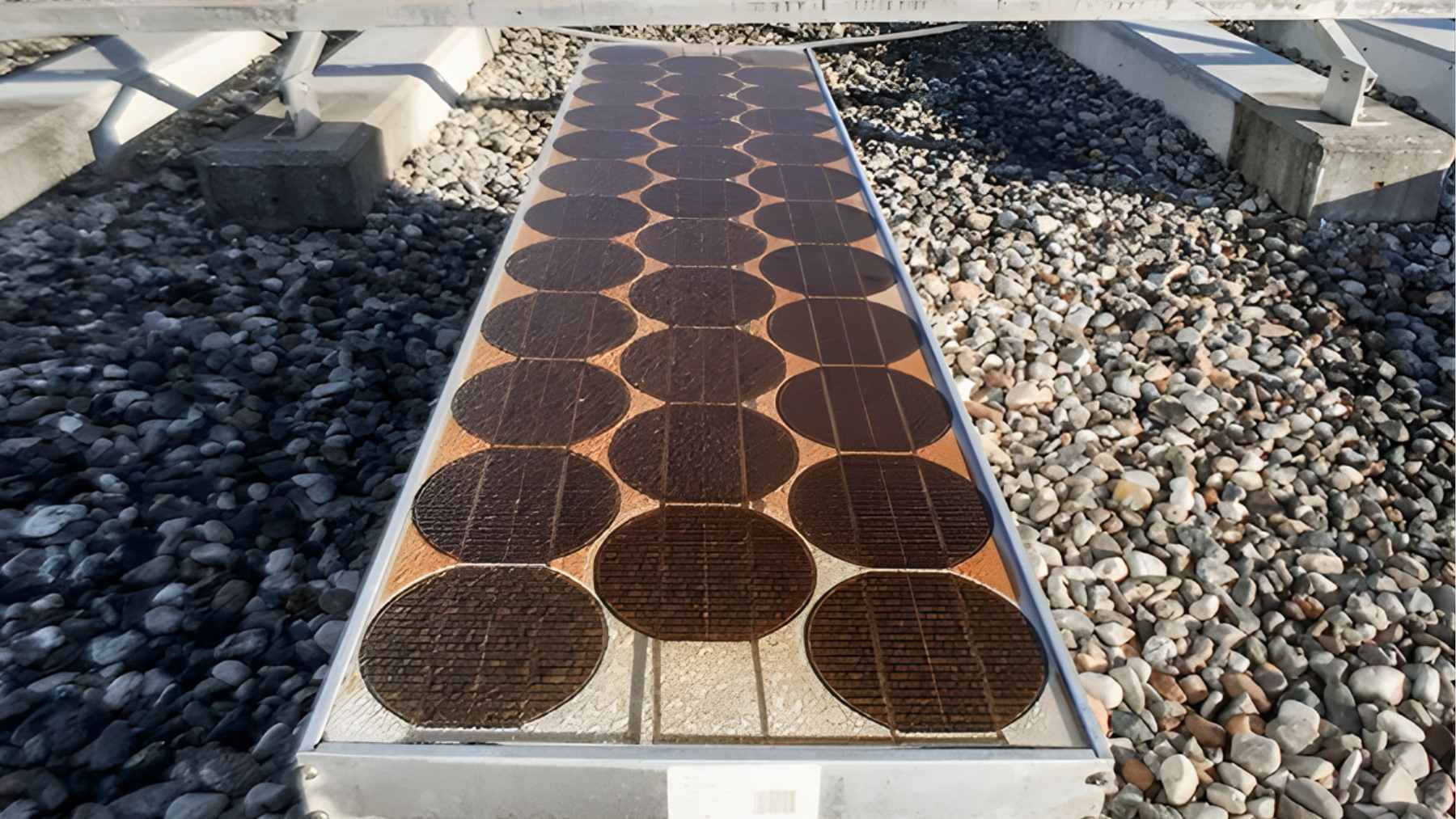

Solar growth puts India on track to reshape the global market

Clean power expansion is at the heart of this story. In the first eleven months of 2025, India added about 35 gigawatts of solar capacity, 6 gigawatts of wind, and 3.5 gigawatts of hydropower, with renewable additions up 44% compared with the previous year. That surge helped India overtake Germany in 2024 to become the world’s third largest generator of electricity from wind and solar.

The momentum is set to continue. Bloomberg’s clean energy research arm BloombergNEF expects India to add just over 50 gigawatts of new solar capacity in 2026, which would nudge it past the United States as the second largest solar market after China, according to reporting by energy outlet The Economic Times. The projection points to steady utility scale projects and growing rooftop systems supported by government subsidies, a mix that could gradually ease pressure on power prices for households and businesses.

Coal use dips as clean power scales up

Despite this clean energy boom, coal still dominates India’s power mix. Fossil fuels supplied about 78% of its electricity in 2024, and the power sector remains the country’s largest source of emissions, even though per capita emissions stay below the global average due to relatively low electricity use.

There are signs of a turning point. An analysis for Carbon Brief by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, shows that coal power generation fell 3% in India and 1.6% in China in 2025, the first simultaneous drop in more than fifty years. The study links India’s decline to record additions of solar, wind, and hydro power, along with milder weather and slower growth in electricity demand.

The race to peak coal before 2030

For this to be more than a one year blip, clean power has to keep outpacing demand. India has pledged to reach 500 gigawatts of non-fossil power capacity by 2030, and it had already crossed 200 gigawatts of installed renewables by late 2024 according to Ember’s earlier work. Analysts say that if India meets those targets, coal power could peak before 2030 even if electricity demand starts rising faster again.

A recent report from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air argues that China, India, and Indonesia now have a realistic path to peak power sector emissions by around 2030, thanks to rapid solar and wind growth. At the same time, the authors warn that continued construction of new coal plants, along with political resistance from coal interests, could slow the shift unless grid reforms and market rules are updated to favor flexible, renewable heavy systems.

A template for other developing economies

At the end of the day, India’s experiment matters far beyond its borders. If a fast growing, lower-income country can industrialize with cheaper solar panels, batteries, and electric technologies instead of building out decades of coal infrastructure, that challenges the old assumption that dirty energy is the only affordable route to prosperity.

For families in big cities breathing polluted air and for rural communities waiting for reliable power, the stakes are very real. Experts stress that India still faces grid bottlenecks, financing hurdles, and the risk of backsliding toward coal when demand spikes, yet the direction of travel is clear enough that other nations are watching closely.

The main report has been published by Ember.