Milk has long been valued for calcium and vitamin D, but a new study points to a different kind of benefit that plays out deep in the colon. Researchers who analyzed tissue biopsies found that higher milk intake was associated with a more diverse community of gut bacteria, while higher cheese intake was linked to lower diversity and reduced levels of certain common microbes.

The headline finding is simple, but the implication is bigger. Dairy is not a single nutritional category. Milk and cheese can correlate with different microbial patterns, even among people who had normal colonoscopies.

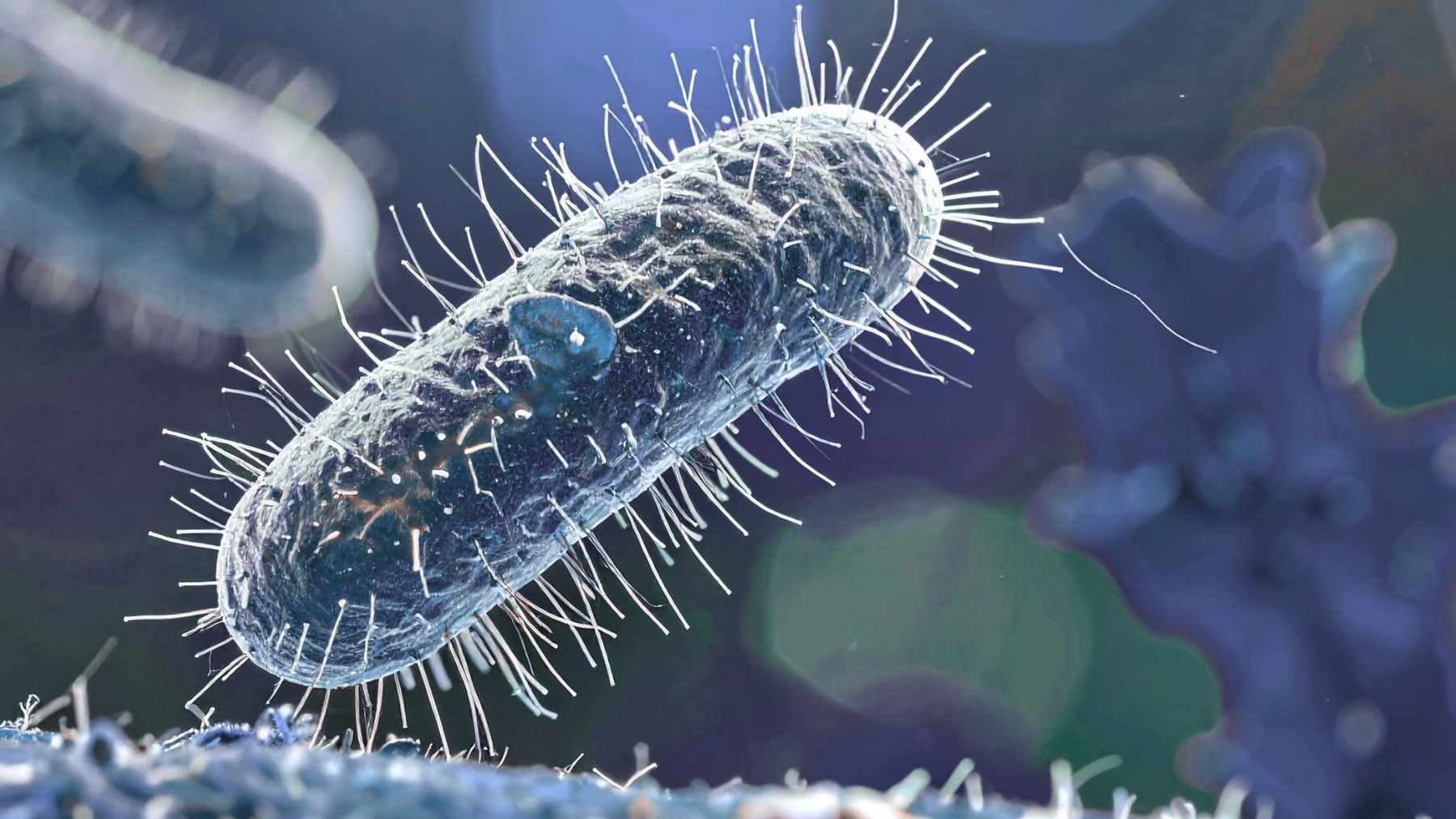

A rare look at microbes on the colon wall

Most microbiome studies use stool samples. This team focused on mucosa associated bacteria, meaning microbes attached to the colon lining that sits closest to immune cells and the gut barrier.

To do that, they analyzed 97 mucosal biopsies from 34 polyp-free participants recruited at a Veterans Affairs medical center in Houston, Texas. Participants reported their usual dairy intake over the prior year using a food frequency questionnaire.

The study group was older and mostly male. Their dairy intake was also modest compared with common U.S. recommendations. Median daily intake was 0.57 servings of total dairy, 0.24 cups of milk, and 0.27 milk equivalent servings of cheese. Yogurt intake was close to zero.

Milk and the bacteria researchers watch closely

When the researchers compared higher versus lower intake groups, higher total dairy and higher milk intake were associated with higher alpha diversity, a measure of microbial richness and balance. Higher cheese intake moved in the opposite direction.

Milk intake was also associated with higher relative abundance of Faecalibacterium and Akkermansia. These genera are frequently studied because they are tied in other research to anti inflammatory signaling, short chain fatty acid production, and gut barrier related pathways, although their effects can depend on the wider diet and health context.

Cheese showed a different signature. Higher cheese intake was associated with lower relative abundance of Bacteroides and lower Subdoligranulum. Those shifts are not automatically good or bad, because the same microbes can be linked to different outcomes across studies, but they underscore that milk and cheese are not microbiome twins.

Why lactose might matter more than people think

One detail in the analysis hints at a plausible mechanism. When the team adjusted their models for lactose intake, the associations between milk or total dairy and higher counts of Faecalibacterium and Akkermansia were weaker. That does not prove lactose is the driver, but it suggests that milk’s carbohydrate fraction could be feeding certain microbes.

That idea also helps explain the milk versus cheese split. Many cheeses contain far less lactose than milk due to fermentation and processing, so two foods that share a label can deliver very different microbial inputs.

Yogurt was not the star of this dataset

Yogurt often gets the probiotic spotlight, yet the study did not find clear links between yogurt intake and the bacteria highlighted for milk and cheese. The most likely reason is basic statistics. With yogurt intake near zero in this group, there was not enough variation to detect meaningful patterns.

What readers should take away

This was a small, cross sectional study, so it cannot show cause and effect. People who drink more milk may differ in other ways that also shape the gut, even though the researchers adjusted for factors such as age, BMI, smoking, alcohol use, and overall diet quality.

Still, the work adds a useful caution for one size fits all nutrition talk. If future studies confirm these patterns in larger and more diverse groups, dietary guidance may need to specify not just how much dairy people eat, but which dairy foods they choose.

The authors summed up the careful conclusion this way. “Dairy consumption may influence host health by modulating the structure and composition of the colonic adherent gut microbiota.”