A walk along the mudflats of Blue Anchor on England’s west coast has helped scientists put a name to a sea monster that may have matched a modern blue whale in length. Fossil hunter Ruby Reynolds was 11 when she spotted chunks of an enormous lower jaw in May 2020. That bone, combined with a similar jaw fragment found nearby in 2016, has now been formally described as a new genus and species of giant ichthyosaur called Ichthyotitan severnensis, or “giant fish lizard of the Severn.”

The research team, led by paleontologist Dean Lomax, reports that the best preserved jaw element, a surangular bone from the lower jaw, would have been more than 2 meters long when complete. Using cautious scaling based on other ichthyosaurs, the authors estimate the animal’s total body length at roughly 25 meters, placing it in the 20 to 26 meter range. If those numbers hold up as more fossils are found, it would make Ichthyotitan the largest marine reptile formally described so far.

Reuters quoted Lomax calling the discovery “very exciting,” while the scientific paper itself emphasizes the limits of working from incomplete remains. That tension is part of what makes this story so compelling. It is a record breaker built from fragments, and it is also a reminder that science moves forward carefully, even when the headlines want certainty.

A jawbone that changed the conversation

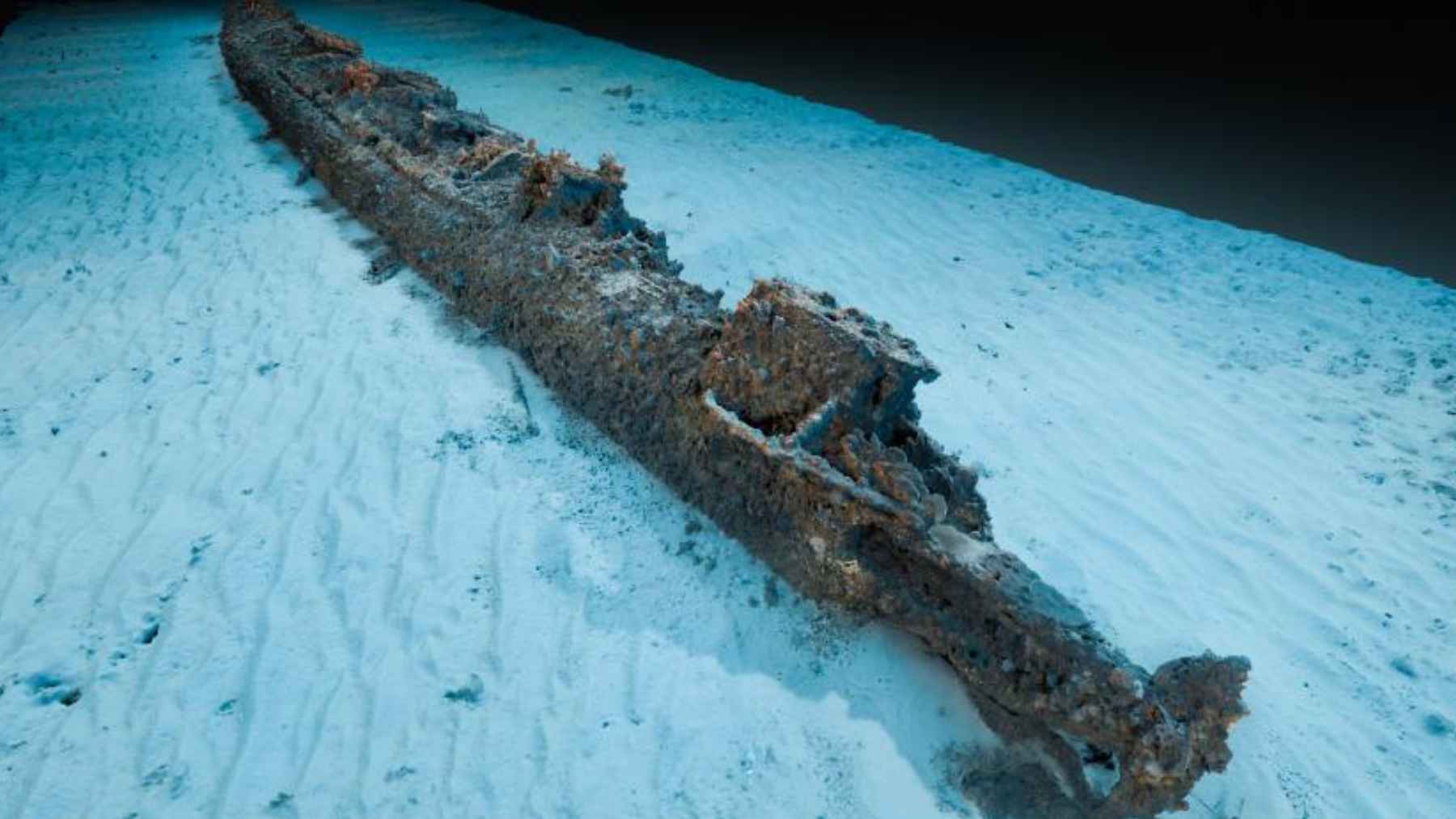

The Blue Anchor specimen was recovered in multiple pieces, some left on a boulder by an unknown member of the public and others found nearby on the foreshore. The team later collected additional fragments over repeated visits, eventually reconstructing nearly two thirds of the giant jaw element.

Those pieces closely match the earlier Lilstock specimen, found about 10 kilometers away in the same geological unit, the Westbury Mudstone Formation. Because both bones share an unusual shape and internal structure, the researchers argue they represent the same new species rather than two unrelated giants.

The formal description appeared in PLOS ONE on April 17, 2024, and the journal later published a correction on January 16, 2025. The existence of that correction is part of the public record, and it is also normal in scientific publishing, where even small fixes are logged transparently.

What scientists can learn from a single bone

It is tempting to treat a giant jaw as a simple measuring stick, but the paper goes deeper than size. The team sampled the fossil’s microstructure and found distinctive histological features also reported in other giant ichthyosaur specimens. In plain terms, the bone carries a growth pattern that suggests these animals may have had an unusual way of building and remodeling jaw tissue compared with smaller relatives.

One especially striking detail is that the outer region of the bone shows signs consistent with continued growth at the time of death. The authors interpret this as evidence the animal was still growing, meaning the biggest individuals in this lineage could have required prolonged growth strategies to reach their final size.

That idea is intriguing, but it also underlines why the researchers keep repeating the same point. Without a more complete skeleton, every estimate has to stay provisional.

A giant living near the end of an era

Ichthyotitan severnensis lived around 202 million years ago in the late Triassic (the Rhaetian age), a time when parts of what is now the United Kingdom were covered by shallow seas. The layer immediately above the fossil bearing rock records upheaval near the Triassic Jurassic boundary, when a mass extinction reshaped life in the oceans and on land.

The authors suggest this lineage of giants likely vanished during that end-Triassic crisis, and ichthyosaurs never again reached such enormous sizes.

Why a local beach matters to global science

There is an environmental angle here that does not require any hype. The Somerset coast is dynamic. Cliffs crumble, storms move sediment, and new surfaces are exposed. That natural erosion can reveal fossils, but it can also destroy them quickly once they reach the shoreline.

The practical takeaway is simple. If you find something unusual, document it, handle it responsibly, and contact local experts or museums. The Blue Anchor discovery moved from beach to peer reviewed science because the finders reached out, and because a community of collectors and researchers returned again and again to recover what the sea was about to take back.