In early January 2026, the nuclear powered aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln carried out live fire drills in the South China Sea, one of the busiest and most fragile marine regions on the planet. U.S. Navy photos show the ship’s Phalanx Close In Weapon System blazing from the flight deck on January 8 while the carrier strike group conducted what officials described as routine operations.

On paper this is a familiar security story. A U.S. Navy supercarrier in disputed waters, patrols meant to reassure allies, drills framed as a show of readiness. But beneath the surface, quite literally, another story is unfolding. It has to do with coral reefs, whales, fisheries and ultimately the price of seafood and fuel that households see in their everyday budgets.

A supercarrier in a crowded and contested sea

According to official captions on the Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, the Abraham Lincoln strike group has been operating in the South China Sea since late December, running flight operations, replenishment at sea, damage control training and explosive ordnance disposal drills. The timing comes only days after fresh Chinese live fire exercises encircled Taiwan, keeping regional tensions high.

This patch of ocean is not only a geopolitical hotspot. By some estimates, it carries around thirty to forty percent of global shipping by certain measures, including container traffic and vessel movements. Every smartphone, car part and tank of fuel that moves through these sea lanes means more traffic, more noise and more risk before a single warship even arrives.

Biodiversity hotspot already under strain

For marine scientists, the South China Sea is a jewel box. Studies suggest it hosts roughly 571 species of reef building corals, a richness on par with parts of the famous Coral Triangle, even though its reef area is much smaller. Broader surveys count thousands of marine species, from reef fish to sea turtles, packed into shallow shelves and atolls.

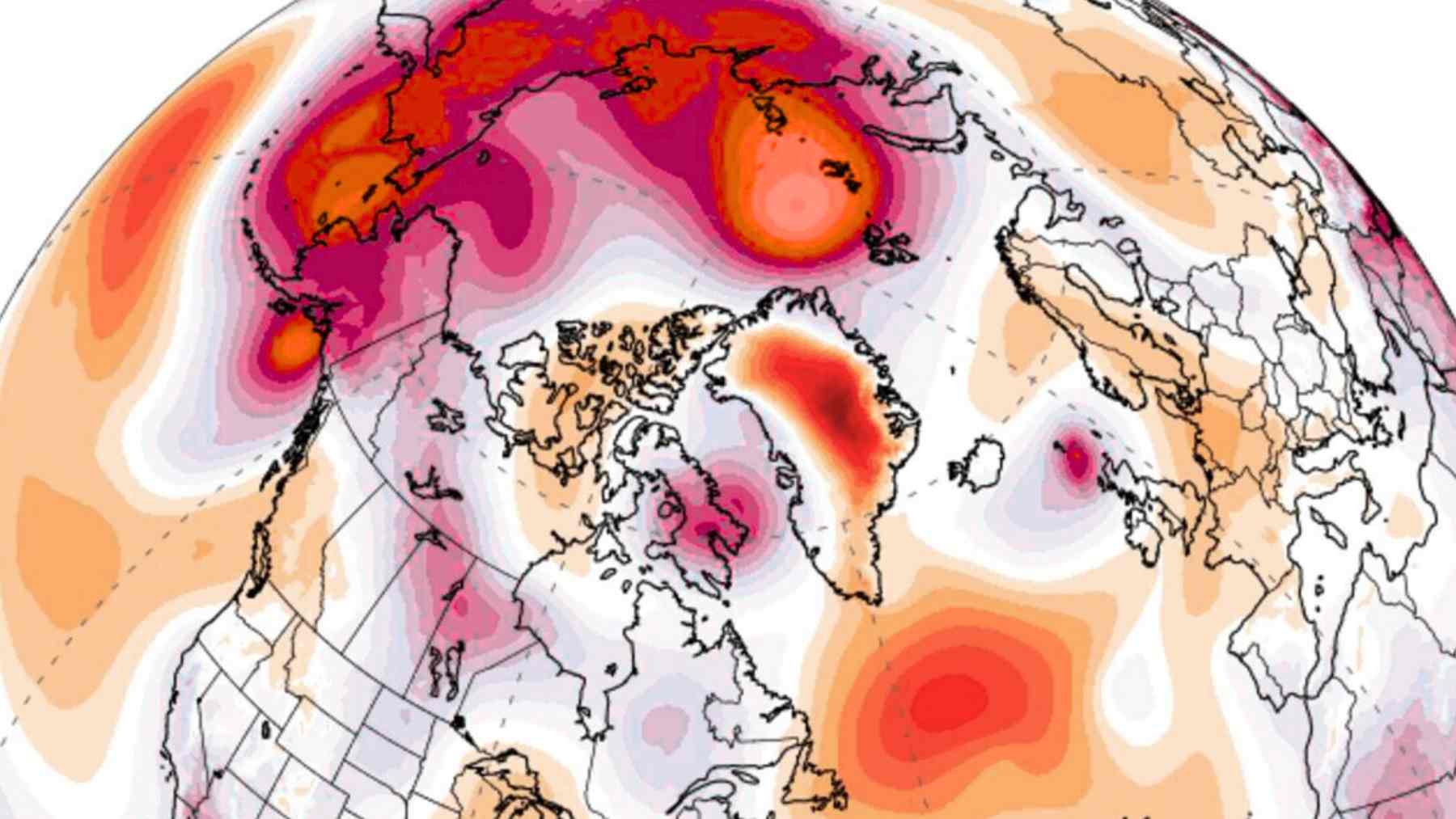

That living wealth is already in trouble. Satellite and field analyses have documented at least eight thousand acres of damaged reef across the region. About two thirds of that has been linked to large scale dredging and artificial island building, mostly by China, which scientists say causes long term and sometimes irreparable changes to reef structure. Fishing pressure, coastal development and heavy shipping add more stress.

Now layer military activity on top of that. Carrier groups, coast guard flotillas, maritime militia vessels, all moving through the same contested waters that support regional food security. At the end of the day, the ecosystem is the one player that cannot walk away from the table.

Noise, live fire and stressed marine life

Live fire drills like those conducted from the Abraham Lincoln introduce high energy impulses into the air and water column. Even when the rounds are aimed safely away from other vessels, fragments and noise still enter the marine environment. Studies on naval and industrial exercises in other oceans show that explosives and intense sound can injure fish, damage invertebrates and disturb feeding or spawning behavior.

Underwater noise is a growing global concern. A recent scientific review described marine noise pollution as a major environmental problem, driven by ships, seismic surveys and military activity. Research linked high intensity sonar and similar sound sources to mass strandings of beaked whales and other cetaceans, with effects ranging from behavioral disruption to physical injury.

No one has published a study yet that isolates the specific environmental footprint of this single carrier deployment. That would be unrealistic. Instead, experts warn that each new round of exercises adds to a cumulative load of noise, pollution and risk in a semi enclosed sea where ecosystems are already close to their limits.

Law, security and the missing green conversation

Back in 2016, an arbitral tribunal under the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled that sweeping historic claims in the South China Sea had no legal basis under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The same proceedings highlighted how large scale land reclamation and construction had severely harmed coral reefs and violated obligations to protect fragile ecosystems and habitats of threatened species.

That legal logic cuts both ways. It is not only about one claimant. All states operating there, including the United States and regional coastal nations such as the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia, share responsibilities to prevent unnecessary harm to the marine environment.

The U.S. government has acknowledged the issue in its own way. Navy training ranges are now covered by detailed environmental impact statements, and NOAA Fisheries authorizations describe acoustic and explosive stressors as likely to affect whales, dolphins and other marine mammals, with required mitigation such as exclusion zones and shutdown rules when animals are spotted. Yet most of that conversation happens far from the public eye, buried in technical documents.

Why this matters far from the reef

It can be tempting to see these drills as something abstract. Warships, far away, doing what warships do. But the same waters feed regional seafood markets, shelter corals that help buffer coasts from storms and keep trade routes open so that lights stay on and air conditioners hum through the sticky summer heat we all know.

Security planners argue that visible patrols keep shipping lanes safe. Environmental scientists answer that a safe sea is also one where reefs, fish stocks and marine mammals are still functioning decades from now. To a large extent, both sides are talking about stability, just on different time scales.

Bringing those time scales together is the challenge. It means treating each new deployment, whether Chinese island construction or American carrier drills, not only as a signal to rivals but as another stress test for a crowded ocean basin.

The official statement was published on DVIDS.