After 250 years on the seafloor, a lost 18th century explorer ship has been found perfectly preserved off the coast of Western Australia. For maritime archaeologists, the discovery looks less like wreckage and more like a time capsule from another age. For the rest of us, it offers a brief glimpse of a long-vanished voyage.

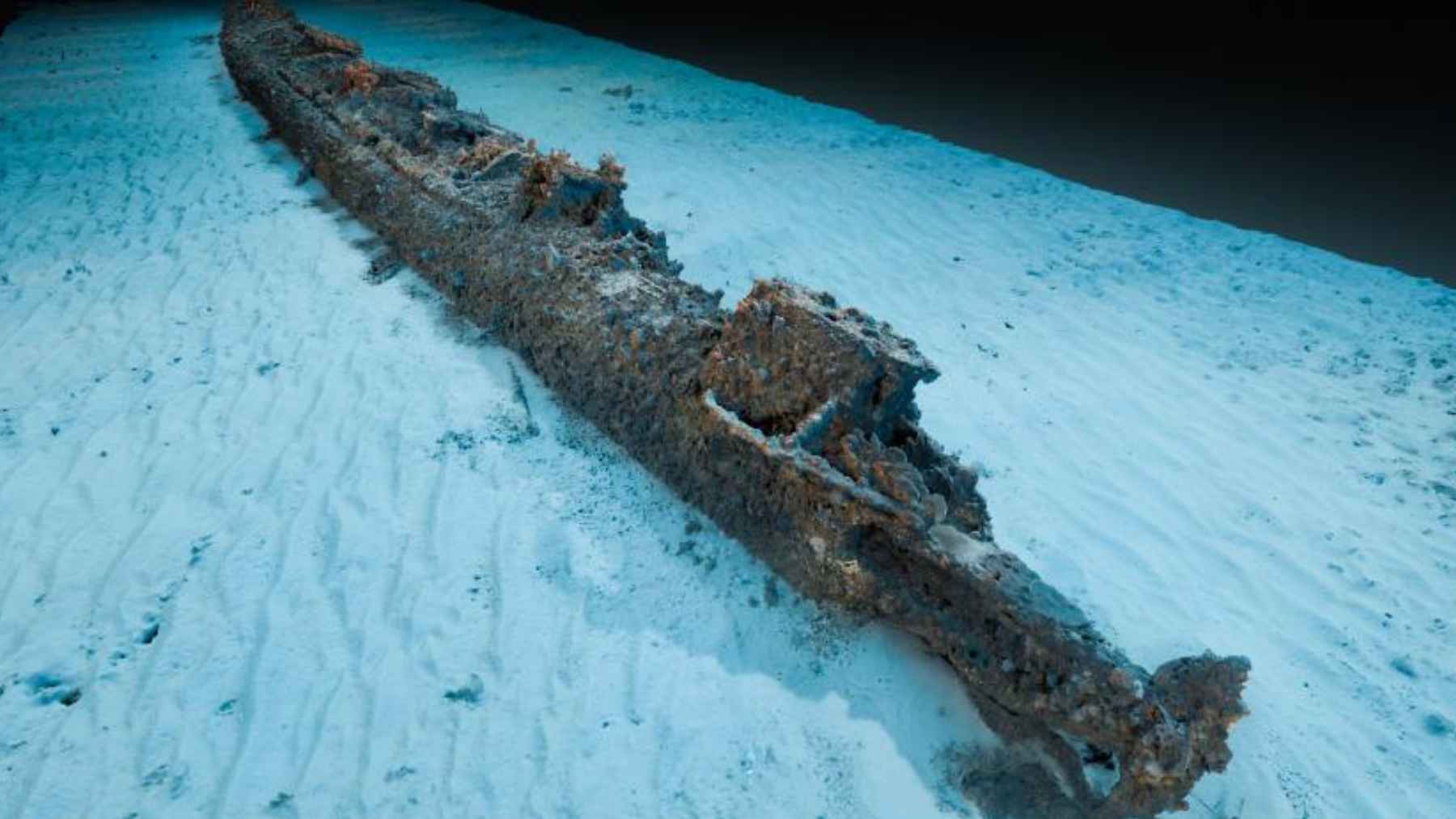

The wreck first appeared as a faint blur on a sonar screen, a pale, straight line where the seabed should have looked smooth. When a robot sub dropped into the dark water, its camera revealed a wooden hull standing upright, bow sharp in the gloom, a ship that had vanished from human sight for generations.

What else might still be waiting in the dark on that same stretch of seafloor?

A ghost ship rises from the sonar

On deck, the research team watched the first images in near silence, phones out but voices low. Many had spent years chasing fragments of logs, missing charts, and stories about an explorer who vanished along this coast in the late 1700s. Seeing a whole hull instead of scattered debris felt like history was finally picking up the call.

On screen, barnacles clung to the timber yet the lines of the vessel were unmistakable, a sailing ship from the age when European powers were still sketching in the edges of world maps. The stern windows showed traces of carved decoration, soft but visible under a film of silt.

The anchor lay where the last desperate crew must have dropped it as they tried to save their ship.

Why this wreck survived when others did not

Warm seas around Australia usually tear wooden ships apart within decades as marine organisms chew through planks and ropes. In most cases, wrecks collapse into twisted ribs and scattered iron, leaving archaeologists with clues. This ship is different.

The vessel lies in deeper, colder water where sunlight barely reaches and oxygen levels are low. That dark environment keeps wood-eating organisms sluggish and less abundant, while fine sediment has packed around the lower hull like a protective shell.

For experts, every joint preserved in that shell offers clues about where the ship was built and which shipbuilding tradition it followed.

Inside a frozen night of exploration

Inside, the cabins feel like someone closed the door and walked away. The captain’s quarters still hold the outline of furniture, and drawers may hide navigation charts or even a logbook protected by layers of mud.

The galley shows the ghost shapes of storage barrels with rusted metal hoops but forms that are recognizable at a glance.

It is not hard to picture one of the last nights before disaster. Wind rising, an unknown coastline looming nearby, deadly reefs yards below black water. In those moments, charts were more hope than certainty and one wrong calculation could turn a routine watch into a race to keep the hull afloat.

Slow science and new ways to share the story

Maritime archaeologists often describe their work as detective work for a past that left almost no living witnesses.

By studying how the ship was put together, they can trace where it was built and who paid for the voyage, then match food remains and tools to crew and intermediaries who actually kept the expedition running while also including Indigenous perspectives.

The instinct after seeing such a pristine wreck might be to raise it and build a museum around the whole ship. Real-life science moves more slowly. Australian maritime archaeologists plan to create a digital 3D model, recover only the most fragile and informative objects, and send them to conservation laboratories that can stabilize salt soaked wood and corroded metal.

Plans already include exhibits at Australian museums and online tours that let people explore the wreck without touching it.

The project’s lead archaeologist summed up the responsibility that comes with that public access, saying, “We are not just recovering objects, but decisions; every broken nail and every patch on this hull is a decision someone made.” The main press release has been published by the Australian maritime archaeology project team.

The official information about Australia’s underwater cultural heritage has been published on the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water’s underwater heritage site.