Secret Iron Age “money stash” found in Bohemia may point to a lost Celtic marketplace

Archaeologists working in western Bohemia have uncovered a huge cache of Iron Age valuables at a rural site they are still keeping under wraps. The find includes hundreds of tiny gold and silver coins, chopped bits of precious metal, and finely made ornaments that look strongly connected to Celtic culture in Central Europe.

The big twist is what is missing. So far, researchers have not found clear signs of permanent homes or streets, which raises a simple question. What if this wasn’t a town at all, but a place people returned to only at certain times to trade, pay debts, or meet rivals?

Why the team kept the site quiet

The excavation has been intentionally low-profile for years because the biggest threat is not time, it is people with shovels. Jan Mařík, director of the Institute of Archaeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, said, “The main goal of the project was primarily to save movable archaeological finds that are immediately threatened by illegal prospectors, ploughing and natural influences.”

Many of the objects are small enough to disappear in a single season of farming. Most of the coins measure about 0.28 to 0.59 inches across, which is roughly the size of a fingernail. If you have ever dropped a coin in tall grass and given up after a minute, you get the problem.

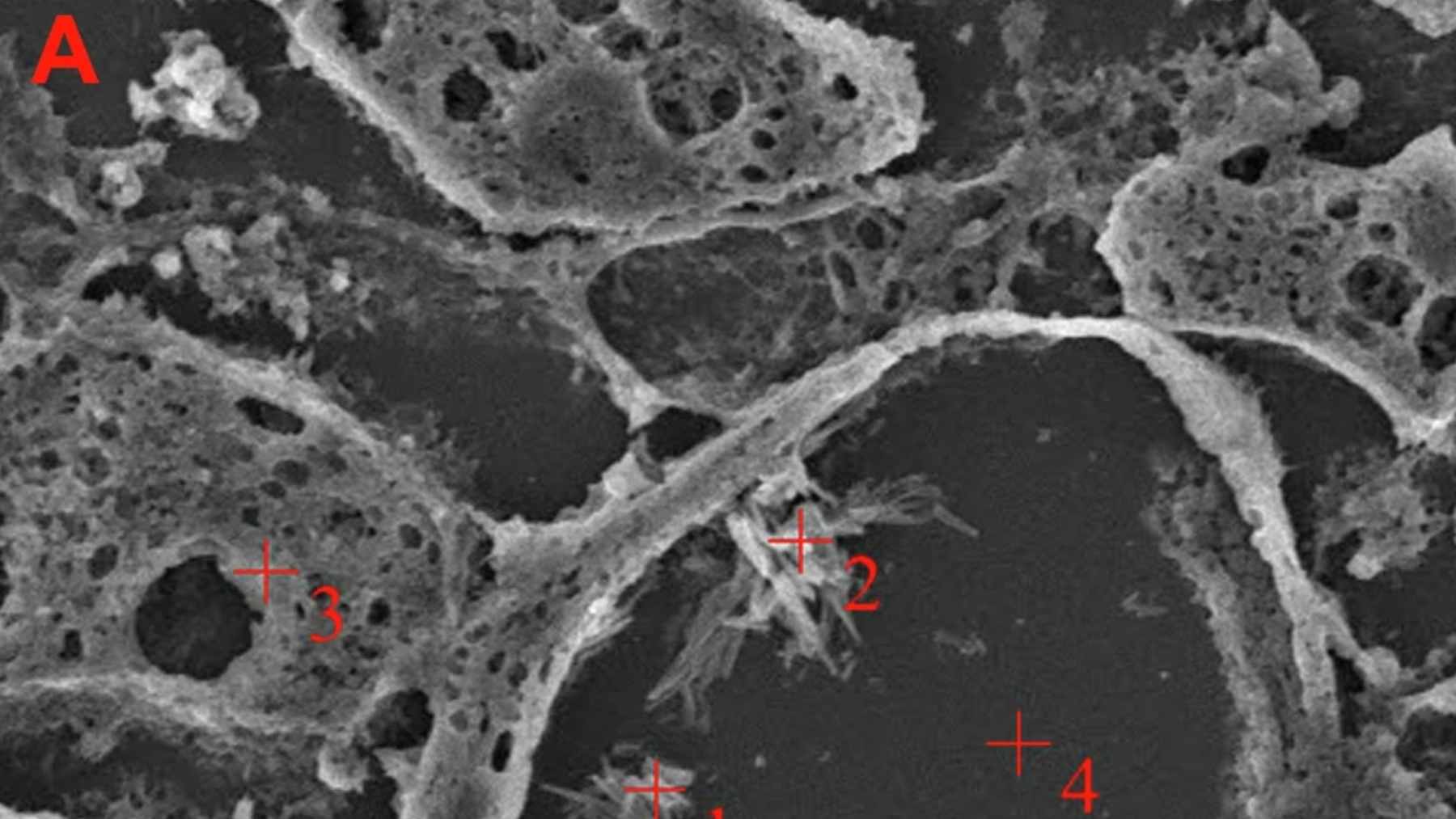

What was actually found in the ground

The collection includes coins stamped with animal designs, fragments of gold and silver that were likely cut on purpose, and ornaments that people wore or carried. Bronze buckles, pins, bracelets, pendants, and a small horse figurine round out the mix, suggesting this was not just “treasure,” but everyday wealth in motion.

Some pieces have been shown to the public through a recent museum exhibition, while the most delicate items remain in secure storage. That choice is about conservation, meaning careful protection of fragile objects so they can be documented before light, handling, or cleaning destroys clues.

A market without walls

Archaeologists say the pattern looks like scattered losses across cultivated ground, not the dense footprint you would expect from a normal settlement. David Daněček, who leads the regional research collaboration on the site, has pointed to the lack of everyday traces of permanent life as a key detail. In practical terms, that makes a seasonal gathering spot a strong possibility.

This matters because the Iron Age in Europe, roughly from about 1200 B.C. to 50 B.C., was a long stretch of change. The objects also span styles tied to the Hallstatt period, from about 1200 B.C. to 450 B.C., and the later La Tène period, beginning around 450 B.C. and lasting into the first century A.D. People may have kept coming back even as fashions, leaders, and trade networks shifted.

Why the coins could rewrite parts of Celtic Bohemia

Researchers say many gold and silver pieces may come from “mints,” places where coins were struck with stamped designs, that specialists have not yet cataloged for this region. That could change how coin experts reconstruct trade routes and local authority, since coin-making usually requires tools, skill, and some level of political control.

The chopped metal and ingot fragments also hint at a flexible economy where raw value moved alongside finished goods. A trader could cut off a small piece to match an agreed weight, then seal the deal with a coin or an ornament. Future lab work can add another layer by using chemical fingerprints in the metal to estimate where the material originally came from, whether local sources or farther-away suppliers.

How this fits with other Czech Celtic discoveries

Bohemia’s name is often linked to the Boii, a Celtic group associated with the region in ancient sources, and finds like this help put real places behind old labels. In July 2025, archaeologists announced a major La Tène era center near Hradec Králové with evidence of workshops and coin production, described in an official announcement. Put side by side, one site looks like production and daily life, while the western Bohemia landscape may reflect exchange and movement.

Protecting the Bohemia site remains the priority because context is everything in archaeology. Pavel Kodera, director of the Museum and Gallery of the Northern Pilsen Region in Mariánská Týnice, said, “The greatest unique items are stored in a safe place and will be presented only after a complete expert evaluation of the entire research.” A slow, careful approach can be frustrating, but it is often the only way to keep the story intact.

The official press release was published on Institute of Archaeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences.