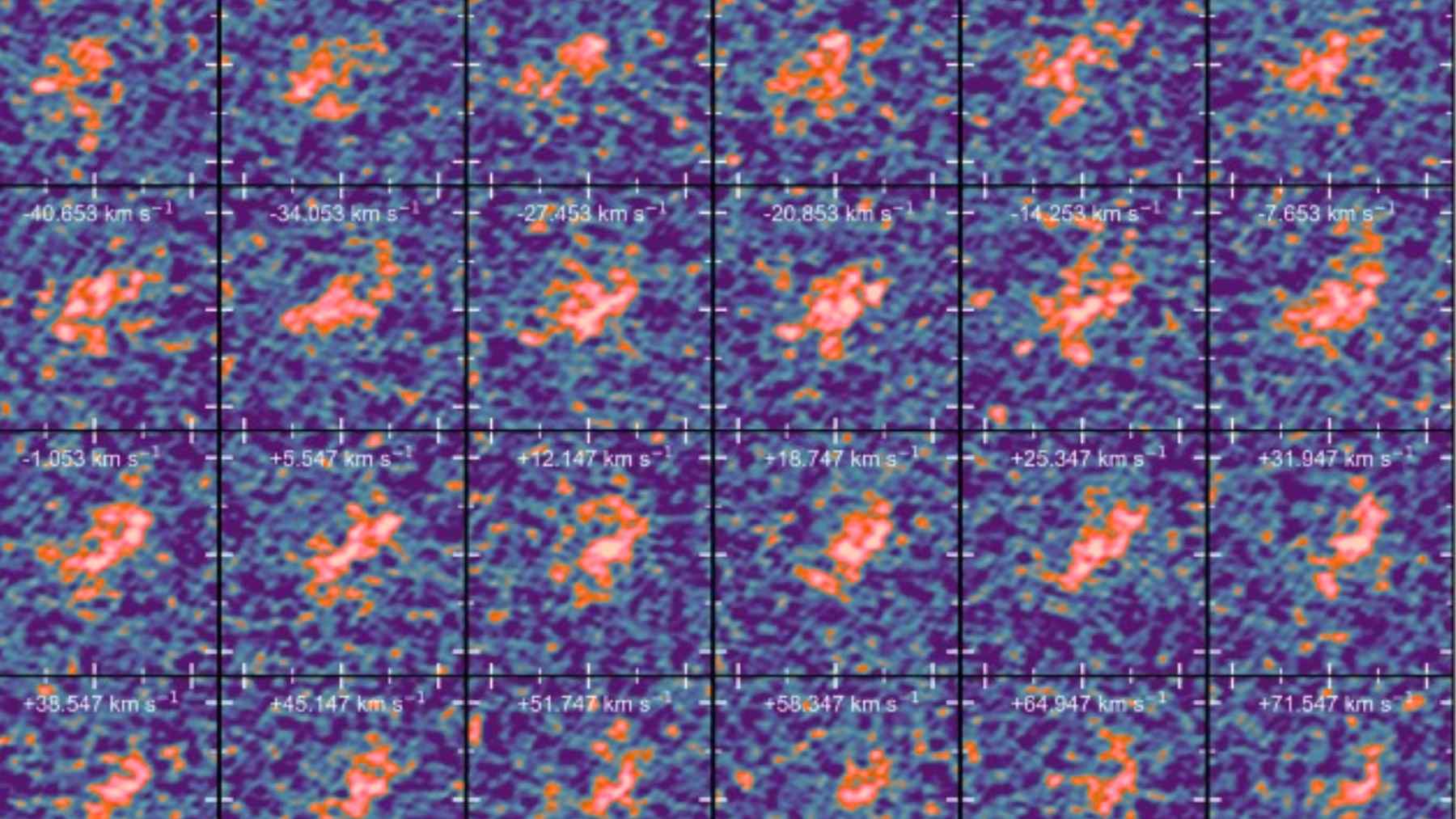

Deep in the sky, astronomers in the United Kingdom have watched aging stars that seem to erase the worlds closest to them. The new study uses data from NASA’s TESS space telescope to show that when stars like our Sun grow old, they often drag nearby giant planets into a fatal embrace. It is a glimpse of what could happen to our own solar system in billions of years.

Researchers from University College London and the University of Warwick examined nearly half a million stars that have started to leave the main part of their lives. These stars have entered what scientists call the post main sequence phase, when hydrogen fuel in the core is running out and the star begins to swell. Among roughly 456,000 of these aging suns, the team found only 130 planets and planet candidates in tight orbits.

That sharp drop in planets around older stars matches long-standing predictions that expanding stars can strip, shred or swallow nearby worlds. Lead author Edward Bryant describes the result as “strong evidence that as stars evolve they can quickly cause planets to spiral into them and be destroyed.”

A census of half a million dying suns

To reach these conclusions, the team turned to NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, better known as TESS. This observatory watches large patches of the sky and looks for tiny dips in starlight when a planet crosses in front of its star. The researchers sifted through more than 15,000 possible signals and ended up with 130 convincing planets or planet candidates.

Overall, only about 0.28 percent of the aging stars in the sample still host a nearby giant planet. For stars that have only just left the main sequence, the rate is closer to 0.35 percent, similar to younger stars. Farther along in their evolution, once a star has cooled and puffed up into a red giant, the share of close-in giants falls to roughly 0.11 percent.

How a star becomes a planet killer

When a star runs out of hydrogen in its core, fusion slows and the outer layers expand dramatically. A Sun-like star can grow to more than one hundred times its original size.

Planets that orbit very close feel this change first. As the star swells, gravity between the star and the planet sets up powerful tides. It is a bit like the way our Moon pulls on Earth’s oceans. Over time, those tides rob the planet of orbital energy, slow it down and make it spiral inward. Some worlds may lose their atmospheres or even break apart before they finally disappear into the star itself.

What this means for Earth

The Sun will eventually follow the same script. Models suggest that in roughly five billion years our star will swell into a red giant and Mercury and Venus will almost certainly be engulfed. Because Earth sits farther out, it may or may not be physically swallowed, depending on how the Sun loses mass as it ages.

Even if the planet itself survives, conditions on the surface would not. Long before the red giant phase, rising solar brightness is expected to boil away the oceans and strip the atmosphere, turning Earth from a blue world into something much closer to a scorched rock.

A long term forecast for a fragile planet

For people worrying about the next electric bill or another heat wave, a five billion year deadline can feel abstract. Yet this cosmic forecast carries a simple message. Habitable worlds are temporary.

By watching nearly half a million distant stars grow old and seeing their closest planets vanish, astronomers have sketched one of the possible final chapters for our own world. The timescale is vast, but the message is down to Earth.

Planetary environments can change in ways that life cannot survive, whether from slow human-driven climate shifts or from the slow aging of a parent star. Understanding both helps us see just how rare and precious a stable home planet really is.

The study was published on the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society site.

Image credits: NASA/ESA/CSA/Ralf Crawford.