Imagine standing in a quiet mountain valley near the Albania-Greece border. You see steam rising from limestone like a kettle left on the stove.

Now picture what’s feeding that steam. More than 100 meters underground, researchers have confirmed a massive thermal lake sitting at the bottom of a deep cave system, and it is now considered the largest underground thermal lake known so far.

The lake, named “Lake Neuron,” lies about 127 meters (417 feet) down inside Atmos Cave in the Vromoner area. Using LiDAR scanning and sonar mapping, the team measured it at about 138.3 meters long and 42 meters wide, holding roughly 8,335 cubic meters of mineral-rich warm water. That is a lot of water to be hiding out of sight.

So why does an underground lake matter to the rest of us, people who are just trying to get through the week and keep the water bill reasonable? Because discoveries like this help scientists understand how groundwater moves, how geothermal systems work, and how fragile some subterranean ecosystems can be.

What makes this lake different from a “normal” cave pool

This is not a chilly puddle in a tourist cavern. The system is part of what researchers call sulfuric acid speleogenesis, a process where hydrogen sulfide rich waters help carve and reshape caves over time.

In the Vromoner area, warm water rises through fractures, and when hydrogen sulfide meets oxygen, it can form sulfuric acid that alters limestone and contributes to large underground chambers.

Measurements in the Atmos and nearby caves show how active the environment still is. In the caves, hydrogen sulfide concentrations in air were measured in the range of about 2 to 22 parts per million in open areas, and cave air temperatures in hydrothermally active spaces were reported between 15 and 29 degrees Celsius.

The lake itself sits at a steady 26 degrees Celsius, and the springs feeding the valley share similar chemistry and temperature. The researchers report the total yield of springs in the Vromoner area at about 200 liters per second.

The water is moving faster than you might expect

Here’s a surprising twist. You might assume deep thermal water rises slowly, like syrup. But dye tracing experiments show the system behaves more like a highly-connected plumbing network.

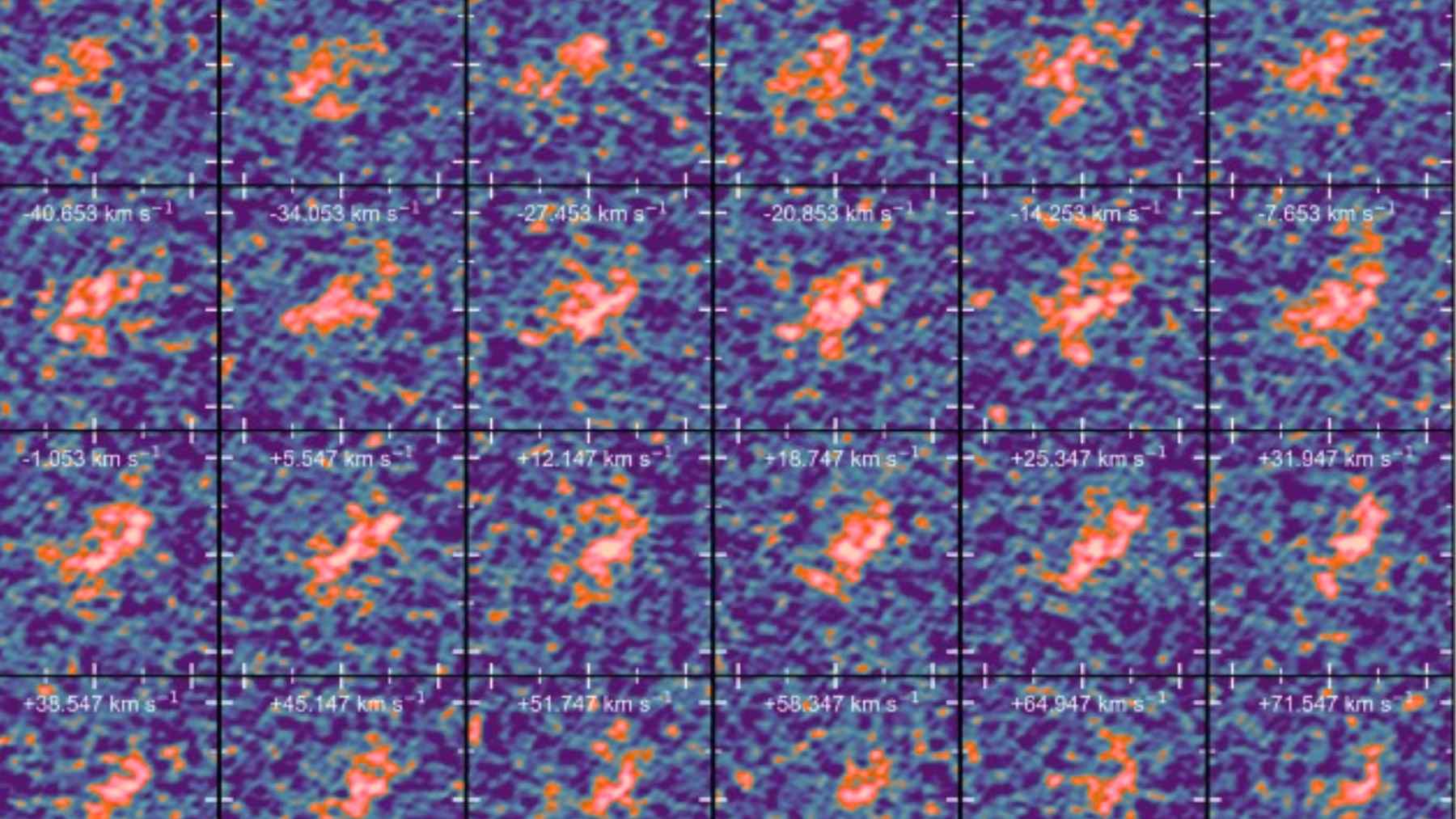

A 2026 paper in the International Journal of Speleology describes tracer tests in this sulfuric acid cave landscape and reports that flow velocities in the Vromoner system can reach up to about 30 kilometers per day.

The same study argues that narrow inflow conduits called “feeders,” once assumed to carry pristine deep water, can actually contain a mix of deep groundwater and recycled water from upstream cave lakes.

In practical terms, that means what happens on the surface, including pollution and land use change, can potentially travel through connected karst systems faster than many people realize.

A hidden ecosystem with real conservation stakes

Warm, sulfur-rich caves are not just geology labs. They can host unusual food webs that rely on chemical energy rather than sunlight, and that can support dense communities of insects and spiders.

One open-access study in the journal Diversity describes Sulfur Cave in the same Vromoner Canyon area as a 520 meter long hypogenic cave with a sulfidic stream and a lake near the entrance.

It reports water temperatures around 27 degrees Celsius and notes that hydrogen sulfide levels in cave air can reach up to 14 parts per million near strong emissions. The researchers also frame their work as baseline data meant to inform conservation actions.

The cave science community working in this region has also raised practical concerns. A technical report on the Atmos and Sulfur cave system says the team is collaborating with local authorities and working toward having hypogene caves included within Vjosa National Park, while warning that a dam on the Greek side of the Sarandaporo River could negatively affect Sulfur Cave’s habitat.

And that’s the bigger point. Even when a lake is 127 meters underground, it is still part of the living landscape above it.

The study was published in the International Journal of Speleology.