Giacomo Ciamician, a visionary in chemistry, warned us back in 1912. He cautioned that the use of coal and fossil fuels had an expiration date and that humanity needed to look where it should have always looked: at plants. His theory was that we could use chemical processes similar to those used by nature to generate energy. For a century, this was just a nice theory, an idea sleeping in the drawers of theoretical science because we didn’t have the materials or the engineering to make it a reality. Until now.

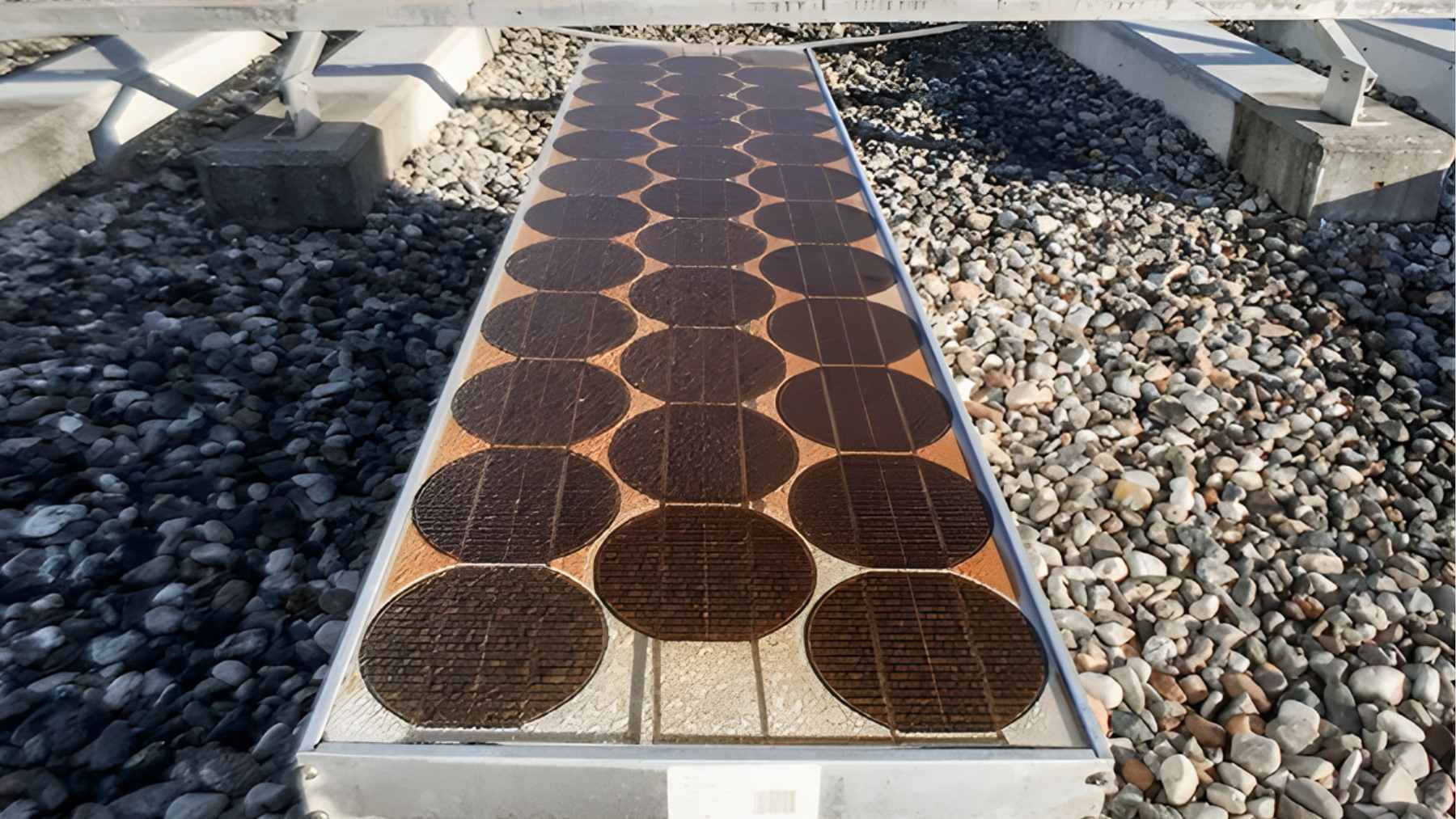

Researchers at the University of Cambridge have confirmed what many were hoping for: they have developed the first artificial photosynthesis system capable of generating clean energy continuously. This isn’t a simple lab experiment that works once and shuts off; it is a scalable platform that converts sunlight, water, and CO₂ into storable energy. It is, in essence, an artificial leaf that works.

How the system that mimics nature works

The Cambridge approach is fascinating because it doesn’t try to reinvent the wheel, but rather copies Earth’s most efficient design. The system emulates the two critical phases of natural photosynthesis. On one hand, the “light reaction” (which consists of splitting water) and, on the other, the “dark reaction” (which is the storage of that chemical energy).

To achieve this, they employ synthetic catalysts and innovative semiconductor materials that trap sunlight. This process converts water into hydrogen and oxygen, allowing energy to be stored in chemical bonds or using that hydrogen to convert CO₂ into useful fuels. Recent scientific literature indicated that it was extremely difficult to reverse-engineer a leaf’s processes (such as light absorption by “antenna chromophores” or charge separation), but this team has managed to overcome that technical barrier.

Why they call it “infinite energy” and what obstacles remain

When Cambridge talks about an “infinite” system, it is necessary to clarify so as not to fall into empty sensationalism. They aren’t suggesting it violates the laws of thermodynamics, but rather that it can operate essentially uninterrupted. It requires very little maintenance and feeds on inputs we have in abundance: sunlight and fresh water.

The design is modular, meaning it is intended to be easily integrated into current energy infrastructure, much like modern solar panels. However, the researchers are keeping their feet on the ground. They recognize that the leap from the lab to the power grid is complex.

There are significant challenges that cannot be ignored, such as the degradation of materials over time or the initial capital cost. The engineering goal now is to improve “solar-to-chemical” efficiency and demonstrate that these devices can withstand years under real-world conditions, not just under controlled laboratory light.

A step toward real decarbonization

If Cambridge manages to scale this commercially, the implications are huge. We could be talking about providing clean energy to remote or off-grid populations, granting energy independence to areas with plenty of sun but few fossil resources.

The association with an institution of Cambridge’s caliber adds a necessary layer of credibility to attract partners and investment. One hundred years after Ciamician dreamed of a solar-powered world, artificial photosynthesis has stopped being a pipe dream and become a functional prototype. The next step will be the battle of cost and installation, but the door to decentralized and truly green energy is now open.