Nearly 40 years after the Chernobyl disaster, gray wolves are still roaming the exclusion zone, hunting, breeding, and in some areas showing higher densities than nearby protected regions. That alone sounds like a plot twist. How can a top predator keep thriving in a landscape still dotted with radioactive “hot spots”?

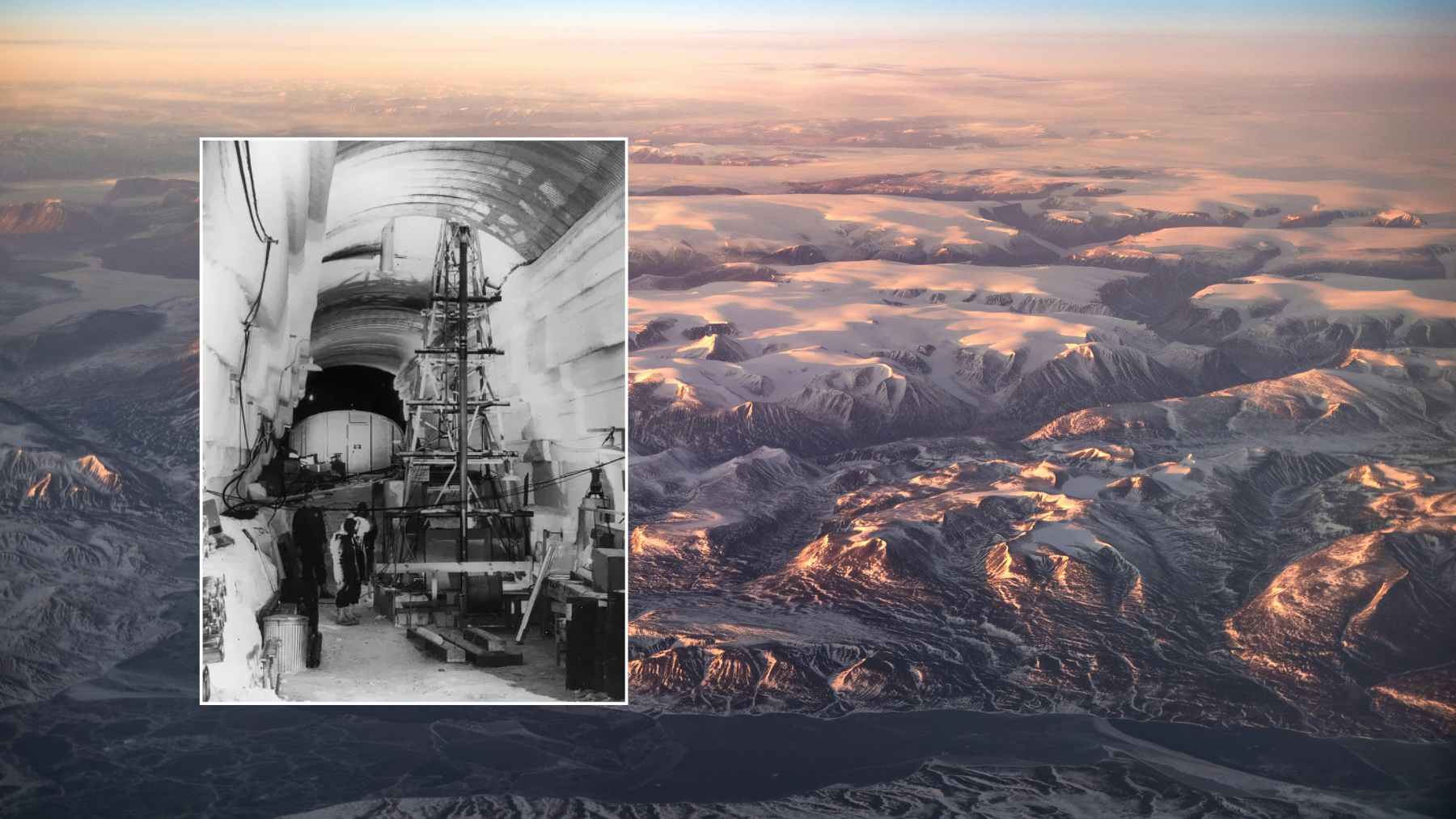

A research team linked to Princeton University has been trying to answer that by tracking wolves with GPS collars that also log radiation exposure. The basic idea is simple. Follow where the wolves go, measure what they’re exposed to, and then compare their biology with wolves living in cleaner environments

A life lived with radiation

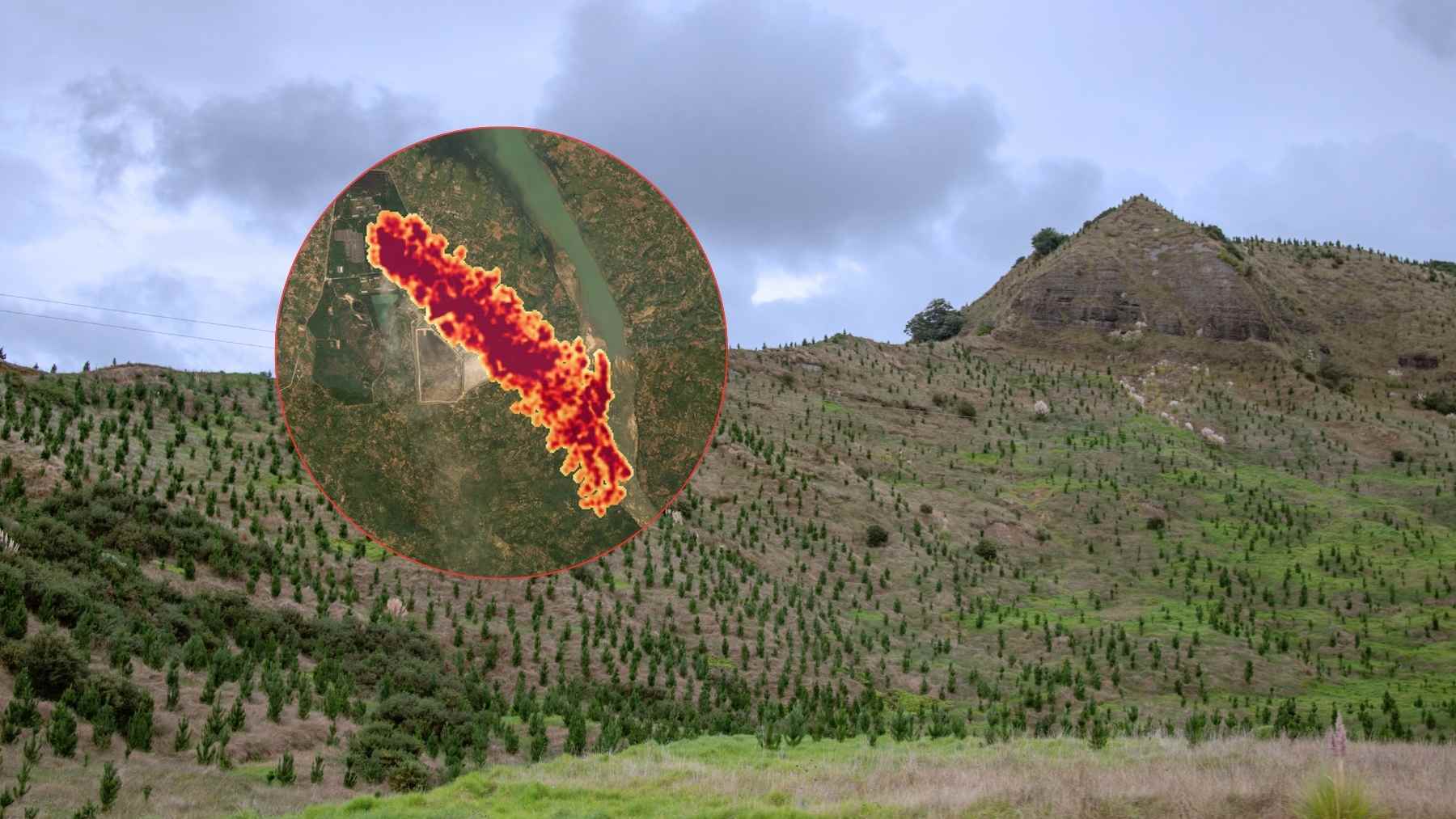

With these collars, scientists can estimate how much radiation a wolf experiences as it moves across the landscape, season by season. Earlier work using GPS-linked exposure monitors in the region showed just how variable exposure can be, even within the same general area, depending on where an animal spends its time.

More recent reporting on this long-running project has pointed to wolves experiencing radiation levels well above what’s allowed for humans, while blood and genetic signals hint at immune changes that could be relevant to cancer biology.

That’s the headline-grabber, of course. “Cancer-resistant wolves.” But here’s the part readers should keep in mind. Much of what’s circulated publicly has come through conference presentations and media coverage, not a single, definitive paper that settles the question for good.

Adaptation or a different kind of advantage

Even if some wolves show biological patterns consistent with better tolerance of radiation-linked damage, that does not automatically mean radiation “made them stronger.” Ecology can be sneaky.

When people leave, wildlife often rebounds. Fewer roads, less hunting pressure, and more available habitat can change survival odds fast. In practical terms, that’s like removing the biggest day-to-day stressor, which can matter as much as any genetic shift. And it’s one reason researchers stress the need to separate radiation effects from other factors like diet, infections, family structure, and isolation.

So what’s the real promise here? If scientists can pin down the immune pathways and genetic regions that help these animals cope with chronic exposure, it could eventually inform how we understand radiation damage and cancer risk. Not as a miracle shortcut, but as a clue worth chasing.

The study was published on Cancer Research.