In China, many of the trash burning power plants that once seemed like an easy answer to overflowing landfills are now facing a surprising problem. They cannot find enough garbage to keep their furnaces running at full speed.

Over the past decade, the country built more than a thousand waste-to-energy plants. Together, they can burn roughly 1 million tonnes of waste per day, a capacity that already sits well above the targets in the latest five-year plan and far above what many cities now generate.

By 2022, official data showed a clear mismatch. Incineration plants were able to handle about 333 million tonnes of household waste per year, while actual collected household waste added up to around 311 million tonnes. Despite that gap, construction continued, widening the shortfall between what the furnaces can burn and what residents actually throw away.

Why the trash mountain is shrinking

Several trends are pushing waste volumes down. Consumption has cooled as the economy slows. The population has begun to decline. Cities have also rolled out stricter rules on sorting, recycling, and food waste separation, which means less mixed garbage reaches the incinerators in the first place.

For most people, this change starts in the kitchen. Separate the food scraps, rinse the plastic, flatten the cardboard. Over time, that routine adds up to hundreds of thousands of tonnes of material that are recycled, composted, or treated separately instead of being fed to the nearest furnace.

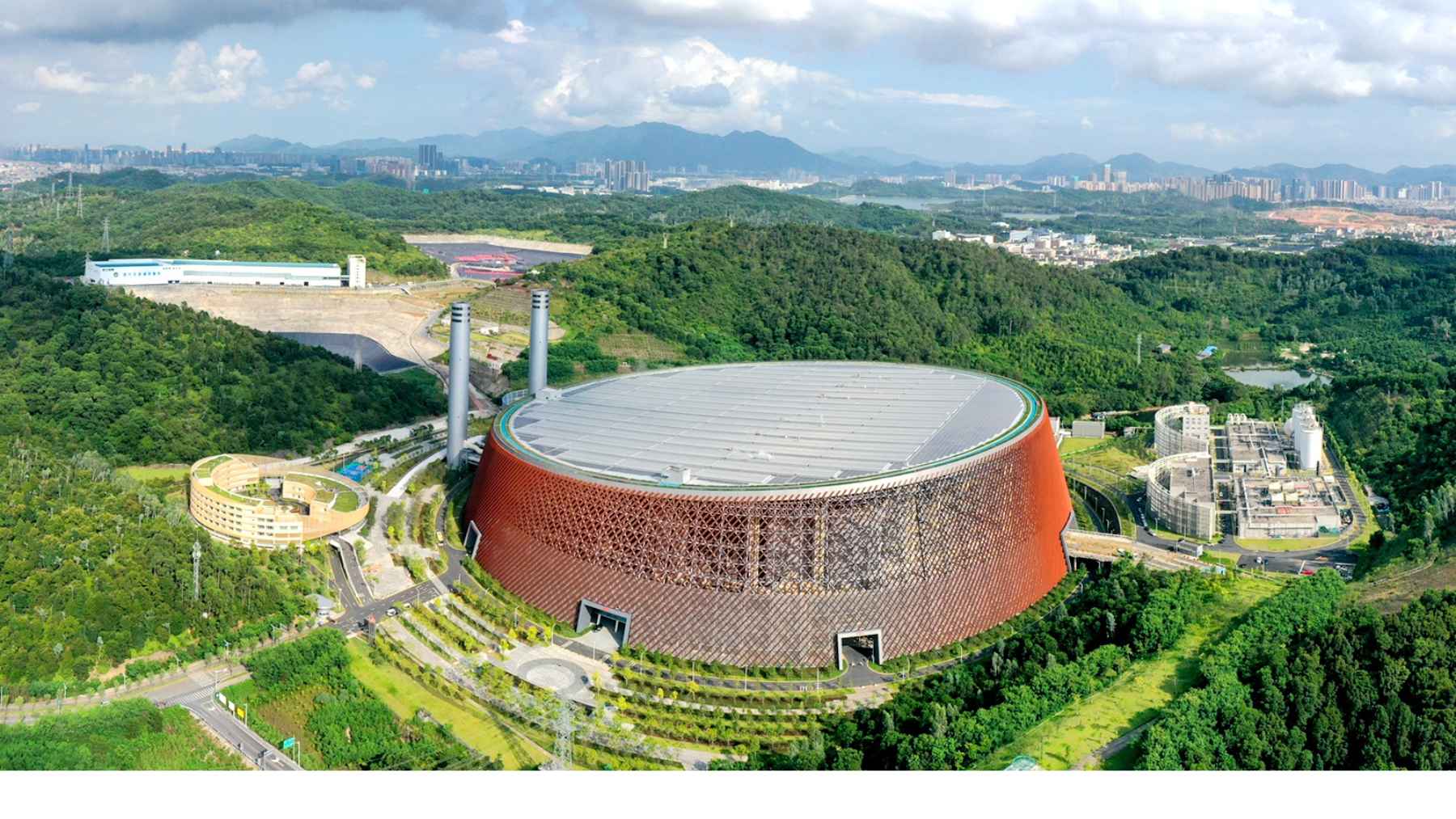

In some large cities, the shift is dramatic. In Shenzhen, authorities report that no household waste now goes to landfill. Five modern incineration plants handle the city’s residual waste alongside aggressive recycling programs.

From an environmental point of view, less trash is good news. For operators who invested heavily in big plants designed to run around the clock, it is a headache.

Plants under pressure

Industry data and media reports suggest that many facilities are now running far below their design capacity. Some sources put average load factors near 60%, which leaves large portions of the system idle and makes it harder to recover fixed costs.

When less waste arrives at the gate, operators look for ways to keep the steam and electricity flowing. They may offer to pay for waste that they once charged to receive, accept industrial or construction debris, or seek permission to co-incinerate sludge and other streams.

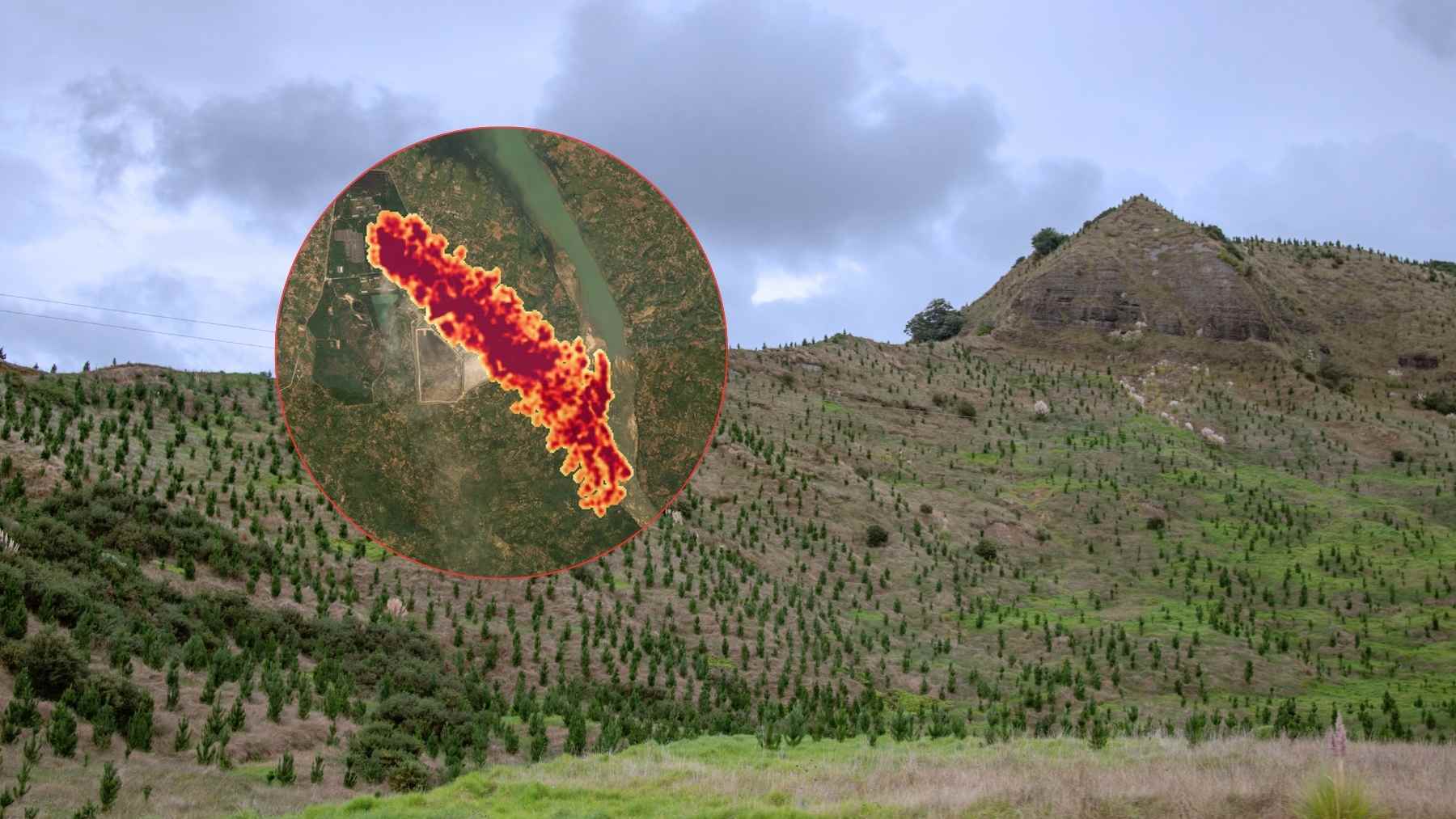

In a few regions, plants or local governments have gone a step further. Crews have begun excavating old landfills, sifting through buried trash to find material that can be burned or recycled. A major relocation project in Shenzhen, for example, processes thousands of cubic meters of excavated refuse every day with on site screening and treatment systems.

China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment has indicated that the current wave of incinerator construction is likely to have peaked, and future efforts will focus more on improving how the existing fleet is run and how its pollution is controlled.

The hidden cost of burning less trash

Even when furnaces run below capacity, they still produce significant byproducts. A recent nationwide analysis in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, based on operational data from 876 plants, found that China’s incineration industry generated about 65 million tonnes of leachate, nearly 8 million tonnes of fly ash, and more than 35 million tonnes of bottom slag in 2022 alone.

Leachate is a polluted liquid that can threaten soil and groundwater if it is not treated properly. Fly ash is a fine powder rich in heavy metals and other toxic substances, officially classified as hazardous waste. Most of it still ends up stabilized and landfilled, with only a small fraction reused in cement kilns or building materials, partly because the economics are weak and construction demand is no longer booming.

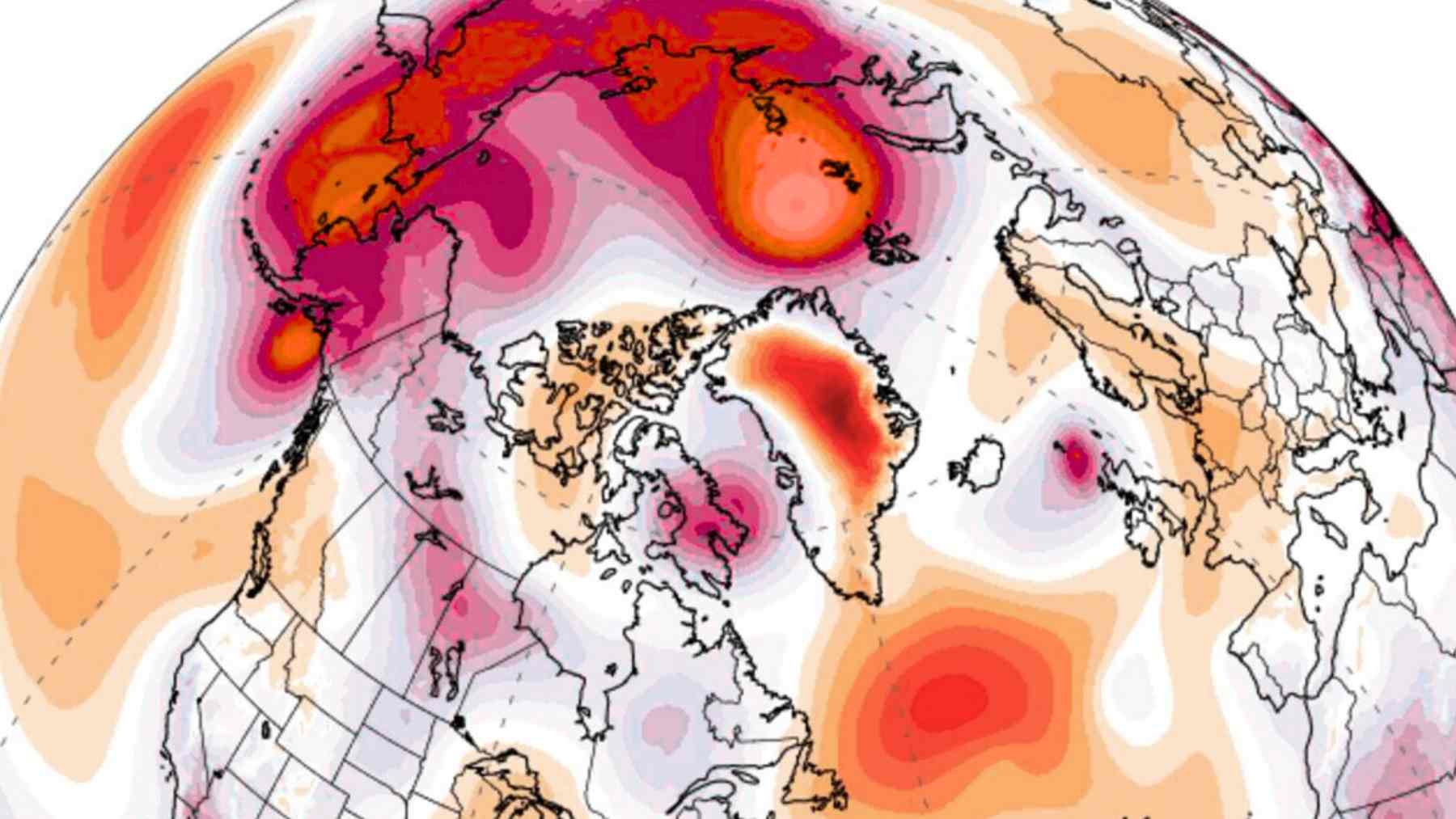

The same study notes that stricter air pollution controls have cut many emissions considerably, and that waste to energy can reduce methane from landfills and even act as a small net carbon sink at the national level. For 2022, the sector delivered an estimated 18.5 million tonnes of negative CO2 equivalent emissions.

So the picture is mixed. Incineration helps with some climate and landfill problems, but it shifts part of the burden into smokestacks, ash silos, and leachate tanks that require constant oversight.

A warning for other countries

At first glance, a country “running out” of waste might sound like a success story. To a large extent, it is. Better sorting and recycling mean less trash is buried or burned. Yet China’s experience also highlights a risk that many fast growing cities around the world are now flirting with.

When governments rush to build large fleets of incinerators as a quick fix for overflowing dumps, they lock in expensive infrastructure that needs a steady diet of garbage for decades. If waste reduction policies work as intended, plants can become underused assets that push operators to seek more material, including from abroad, simply to keep the books balanced and the turbines spinning.

For households, this debate can feel distant compared to something like the monthly electric bill or the recycling bin in the hallway. Yet the choices made today about how to treat trash will shape urban air quality, climate emissions, and land use for years to come.

Experts involved in the national analysis argue that the way forward is not more furnaces, but smarter ones. That means tighter emissions rules, better treatment of leachate and fly ash, more flexible co-incineration strategies, and careful coordination with waste reduction and recycling policies so that plants complement those efforts instead of competing with them.

In other words, China is turning into a real-world stress test for what happens when a country leans heavily on waste to energy, then starts to generate less waste. The rest of the world is watching.

The study was published in Nature.