In a remote corner of the Amazon rainforest, a tiny pollinator has just gained something usually reserved for people and companies. Municipalities in Satipo and Nauta in Peru have approved ordinances that recognize native stingless bees and their habitat as legal subjects with rights to exist, to thrive, and to be defended in court.

It is the first time anywhere in the world that an insect species receives this kind of legal status.

These local rules sit on top of a 2024 reform passedby Congress of the Republic of Peru that brought stingless bees under formal state protection as native bees and as part of the country’s biological heritage.

The ecological importance of stingless bees in the Amazon

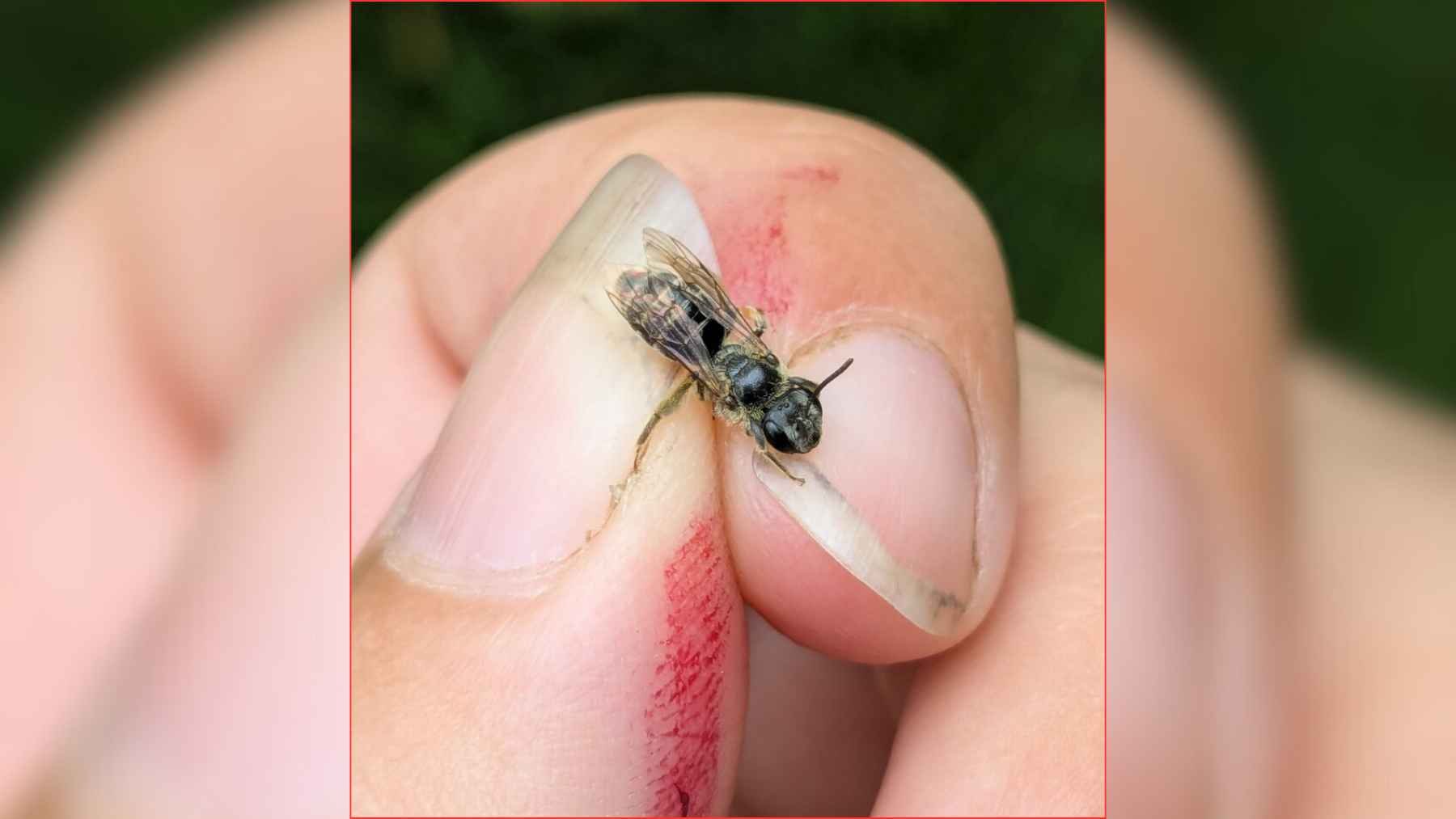

Why should anyone outside the rainforest care about a legal victory for small, black bees that do not sting. Because they quietly support much of what ends up on kitchen tables.

Researchers estimate that about half of the roughly 500 known stingless bee species live in the Amazon region, and that they help pollinate around eighty percent of tropical plant species, including cacao, coffee, avocados and many wild fruits.

In Peru alone scientists have recorded at least 175 native stingless bee species, a number that likely undercounts the real diversity, which places the country among the world’s hotspots for these insects.

A bill of rights for bees: habitat, climate, and legal defense

In practical terms, the Satipo and Nauta ordinances read almost like a small bill of rights for bees.

The texts recognize a right to exist and prosper, to maintain healthy populations, to live in a clean and intact habitat with ecologically stable climate conditions, to regenerate natural cycles, and to receive legal representation if pollution, deforestation or new projects threaten their survival.

Any company, agency or individual that harms their colonies can now be sued on behalf of the bees, with courts required to consider not only human losses but damage to the species and the forest itself.

Traditional knowledge meets modern science

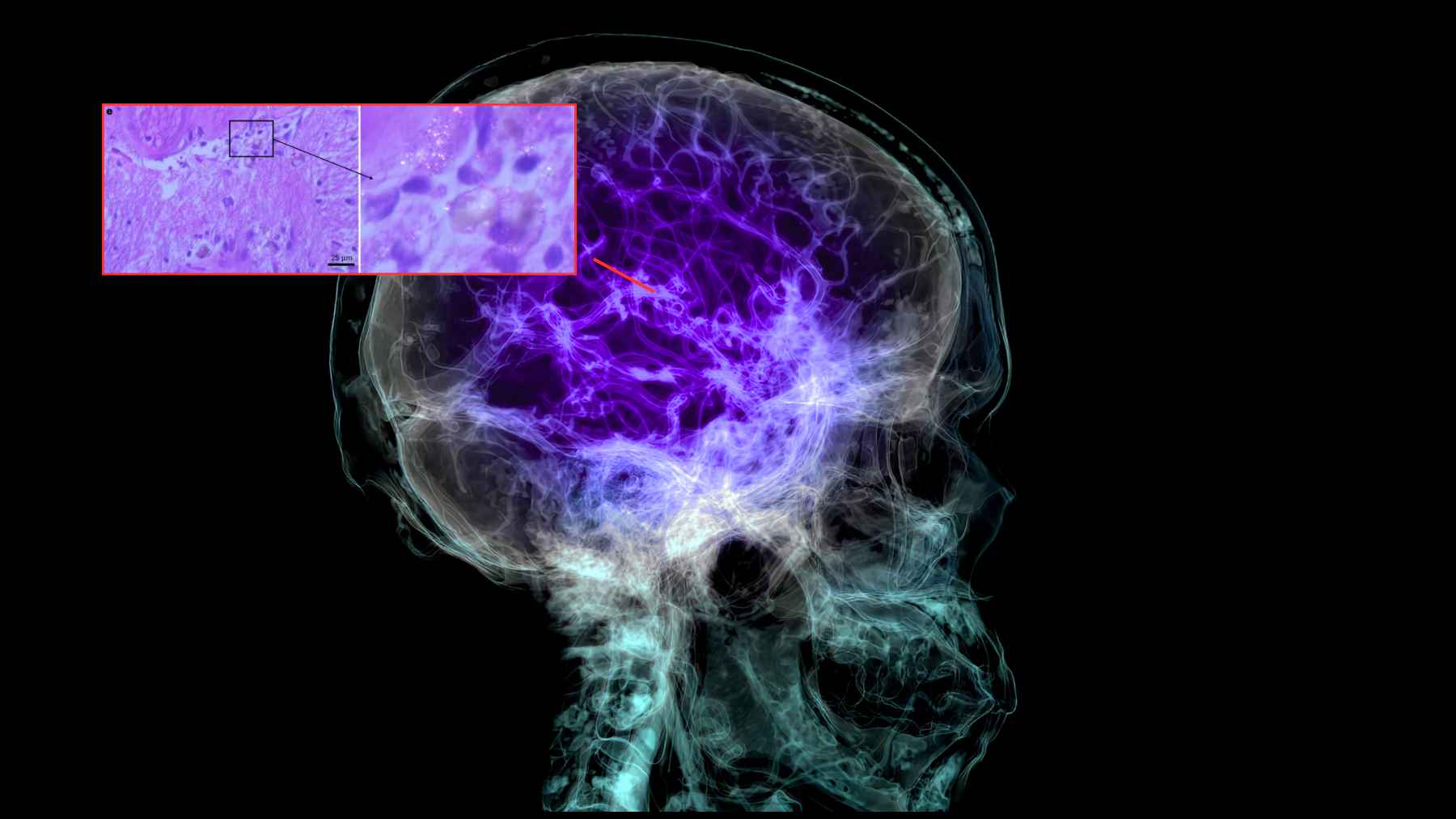

This change did not start in a legal office. It began when chemical biologist Rosa Vásquez Espinoza and her team at Amazon Research Internacional were asked to analyze honey that Indigenous families were using as medicine during the worst months of the pandemic.

Their samples revealed hundreds of bioactive molecules with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and even potential anti-cancer properties, confirming what local healers had said for generations.

From there, researchers and Indigenous elders mapped colonies across large swaths of the forest, documented traditional meliponiculture, and showed how bee numbers dropped where old trees and diverse understory plants disappeared.

For the Asháninka and Kukama-Kukamiria peoples, stingless bees are woven into stories, songs and ceremonies, not treated as simple livestock. As Asháninka leader Apu Cesar Ramos explains, within the stingless bee lives traditional knowledge handed down from grandparents and tied to the rainforest itself.

Environmental law and the role of Earth Law Center

Legal experts at Earth Law Center helped turn that mixture of science and ancestral knowledge into rights-based language. Constanza Prieto describes the result as “a turning point in our relationship with nature” that makes stingless bees visible as “rights bearing subjects” instead of invisible service providers.

Threats to bee populations: deforestation, pesticides, and invasive species

The urgency is clear on the ground. Across the Amazon, stingless bees are under pressure from deforestation, land conversion for cattle and crops, heavy pesticide use, climate-stressed weather patterns and competition from Africanized honeybees that are more aggressive and can take over nest sites.

Elders who once walked half an hour to find a hive now report walking for hours with no guarantee they will see one at all.

Legal protection as a conservation strategy

By recognizing bees as rights holders, Satipo and Nauta are required to move beyond speeches. The ordinances mandate concrete measures such as reforestation in degraded areas, strict control of pesticides and herbicides, restoration of native flora, climate adaptation plans and support for ongoing scientific monitoring.

They also give communities a legal tool to challenge projects that could poison or displace colonies, from road building to new plantations.

Global impact and the future of pollinator rights

The ripple effect is already visible. An international petition backed by global advocacy group Avaaz has gathered hundreds of thousands of signatures that urge Peru to extend these protections nationwide, and groups in other countries are studying the model for their own wild pollinators.

At the same time, scientists point out that safeguarding native bees also protects the wider Amazon, which stores tens of billions of tons of carbon and helps stabilize the global climate.

Pollinators and everyday life: a connection worth protecting

For people far from the rainforest, this story ultimately circles back to daily life. The morning coffee, the chocolate bar after lunch, even that avocado toast all depend to a large extent on pollinators that seldom make the news.

Giving legal standing to stingless bees will not, by itself, save the Amazon. It does, however, shift the legal spotlight toward the small workers that keep forests and food systems running, and invites other governments to ask a simple question. If an insect can have the right to exist, what else in nature deserves a legal voice.

The official statement was published by the Earth Law Center.