Imagine a house whose walls could quietly mend tiny cracks before you ever notice them. That idea just moved a little closer to reality thanks to new research that blends fungus and bacteria into a “living” building material.

A team working at Montana State University has grown a lightweight, bone-like material using the root-like threads of a fungus and special bacteria that turn chemicals into stone. Their study, published in April 2025, shows that this engineered living material stays alive for at least a month and could someday help replace part of the concrete we use in homes and infrastructure, which is a major source of planet-heating pollution.

What are engineered living materials?

Engineered living materials are substances that combine living cells with a solid framework so the material can grow, sense its environment, or repair itself. Think of them as a cross between a brick and a tiny ecosystem, where microbes provide functions that normal concrete or plastic cannot.

Until now, most of these materials have been soft gels or coatings, useful for things like sensors but not strong enough to hold up a building. Earlier work by engineer Chelsea Heveran and colleagues produced “living bricks” made with bacteria that could be grown in sand molds again and again, but their strength and lifespan were limited, especially once they dried out.

How fungus and bacteria grow a new kind of brick

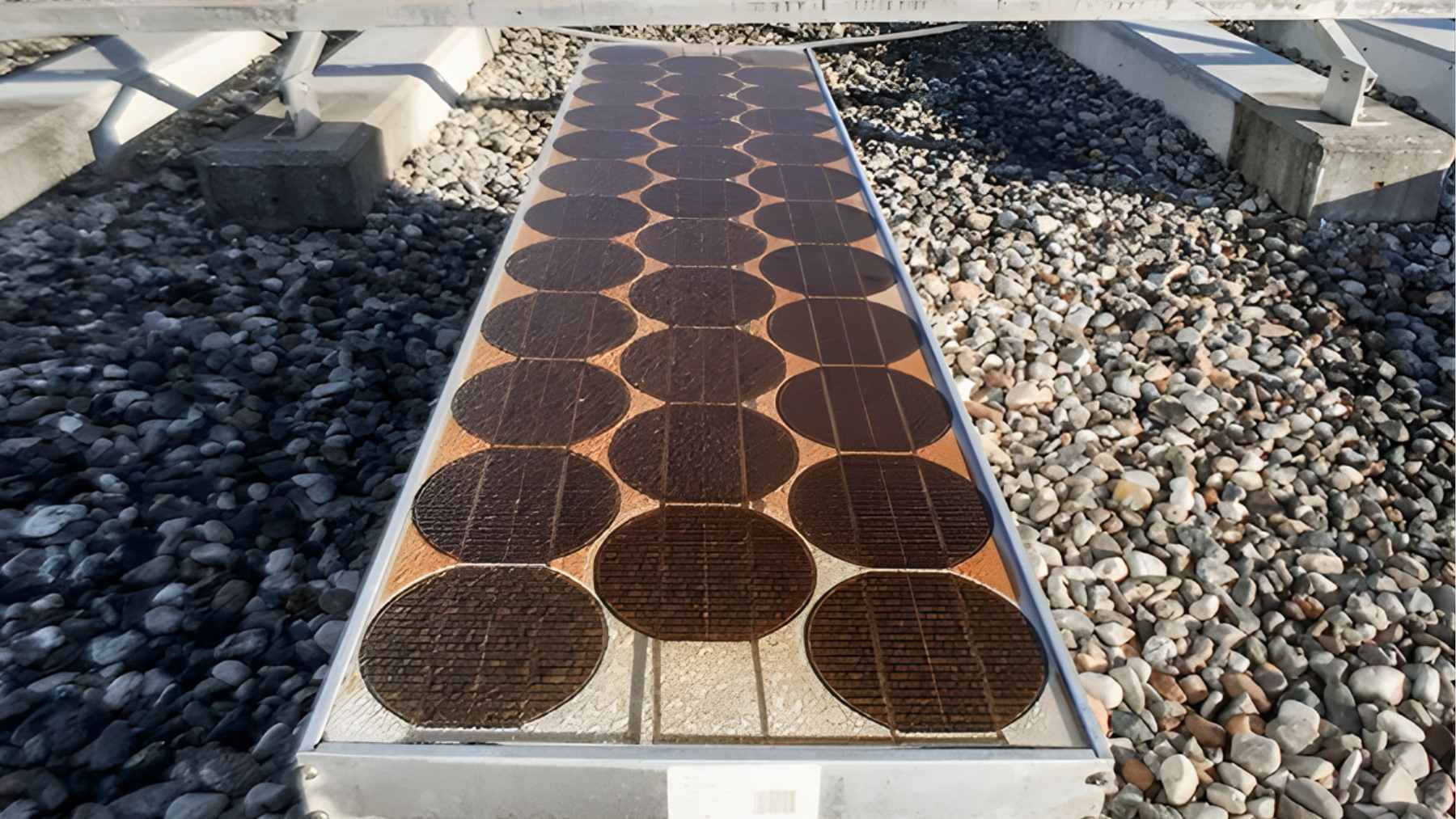

In the new study, first author Ethan Viles and the team started with mycelium, the dense network of filaments that fungi grow underground. They used the species Neurospora crassa, sometimes called red bread mold, and guided its mycelium to fill molds so it formed porous, sponge-like blocks with intricate internal patterns that resemble bone.

Next, they soaked these fungal blocks in a solution containing urea, calcium, and a harmless soil bacterium known as Sporosarcina pasteurii. This microbe breaks down urea and helps form calcium carbonate, the same hard mineral found in shells and limestone, which cements the mycelium scaffold into a much stiffer structure. Similar bacteria are already being tested to “grow” biocement and repair cracks in regular concrete, gluing grains of sand and soil together with new mineral crystals.

Crucially, both the fungus and the bacteria stayed alive inside the mineralized blocks for at least four weeks at warm room temperatures. That longer lifespan is a big step forward, because living materials only have time to repair themselves or clean up pollution if their microbes survive more than just a few days.

Why this matters for climate and construction

Concrete is everywhere: in foundations, bridges, sidewalks, and the apartment towers that shape city skylines. Making the cement that binds concrete together is energy intensive and releases large amounts of carbon dioxide, which is why the cement industry is estimated to cause around 7 to 8 percent of global CO2 emissions. Even as companies test cleaner “net zero” cement using carbon capture, experts still see the sector as one of the hardest to clean up.

On top of the emissions, tearing down buildings creates a mountain of trash. The United States alone generated more than 600 million tons of construction and demolition debris in 2018, more than double the country’s household trash by weight, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Much of that waste still ends up in landfills on the edge of town, even as communities try to recycle more concrete and steel.

Living materials offer a different path. Because they are grown at low temperatures from biological ingredients, they could, at least in theory, be produced near building sites, regrown for repairs, or recycled by grinding them up and using the microbes again. It is a very different picture from firing giant cement kilns all night and trucking in heavy concrete from far away.

Self-repairing walls are still a long way off

For now, no one is about to pour a mycelium-based skyscraper. The new material does not yet match the strength of conventional concrete in all situations, and it has only been tested for weeks in carefully controlled lab conditions. Researchers still need to show that it can handle the freezing winters, scorching summers, and day to day wear that real buildings face.

Even so, the work slots into a broader wave of experiments that try to turn bacteria and fungi into partners in construction. Other teams are developing packets off reeze dried Sporosarcina pasteurii that can be shipped to job sites and activated with water to grow biocement, while reviews of self healing concrete show that similar microbes can seal small cracks by filling them with new mineral deposits. In Europe, the Fungateria project is exploring fungal living materials for walls that could sense their surroundings and even adapt over time.

Most experts expect these living materials to show up first in niche uses, such as lightweight panels, temporary shelters, or structures in remote locations where hauling heavy building materials is expensive. Over time, if scientists can boost strength, lower costs, and prove safety, you could see them quietly blended into more parts of the built environment, from sound-dampening wall tiles to blocks that slowly “heal” microcracks and keep your future home sturdier for longer.

The main study has been published in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science.