For decades, United Nations climate conferences have been the main place where governments negotiate how to cut emissions. Now the president oft his year’s summit in Belém, Brazil, says that system is moving too slowly for a world already living through record heat.

André Corrêa do Lago, the Brazilian diplomat who led COP30, argues that the world can no longer wait for every country to sign off on every step. He says the climate emergency now demands parallel deals among countries, cities, and companies that are ready to move faster than the official talks allow.

Why the COP system is under strain

The annual COP meetings bring together almost every country to agree how to cut greenhouse gas pollution and adapt to worsening heat, floods, and fires. Every decision must be approved by all 195 parties, a rule meant to protect smaller and poorer nations that fear being pushed aside by bigger powers.

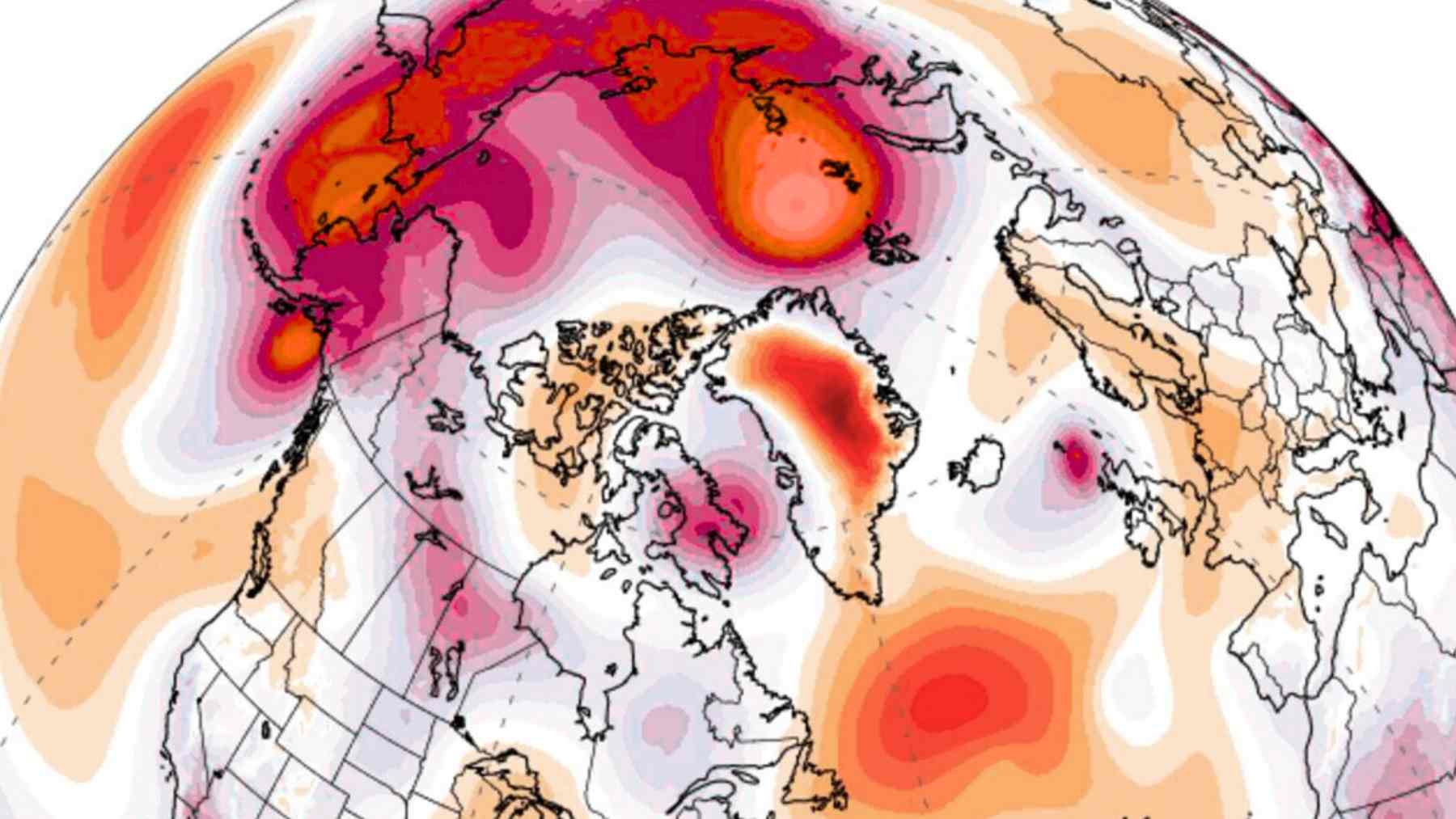

But that same rule has become a brake on action, Corrêa do Lago says, because a single country can hold up an entire text or a small group can repeat long‑standing positions. This slow pace is colliding with a climate reality in which 2024 became the warmest year on record and families are facing burned hillsides, flooded neighborhoods, and higher electric bills as heat waves drag on.

A roadmap blocked inside the talks

The clearest example of this tension at COP30 was a proposed “roadmap” to move the world away from coal, oil, and gas. More than 80 countries, led by the European Union and including vulnerable island states, wanted a shared plan to track how fast nations are cutting their reliance on fossil fuels.

Oil and gas producers such as Saudi Arabia and Russia, joined by large emerging economies including China and India, opposed the idea and pushed back hard. Brazilian officials say more than 35 countries warned they would collapse the talks if the roadmap appeared in the final decision, which meant the plan was dropped from the Belém Package despite strong backing from many others.

Brazil’s plan to work around the deadlock

Faced with that wall of resistance, Corrêa do Lago says the answer is not to abandon the COP system, but to stop expecting it to do everything. Instead, Brazil plans to lead two separate roadmaps over the next year, one focused on the fossil fuel transition and another on deforestation, both developed outside the formal UN process and open to any willing partners.

These informal roadmaps would not be legally binding, but they are meant to give practical guidance on phasing down fossil fuels, protecting forests like the Amazon, and supporting workers and communities through the shift. They sit within what the UN calls the “action agenda,” a side process for voluntary alliances that agree on concrete goals, from electric buses in big cities to methane cuts in the oil and gas sector.

Money, fairness, and blocked ideas

The same consensus rule has also slowed debate over climate finance, the money richer countries and institutions provide so poorer nations can cope with damage and invest in cleaner economies. Developing countries argue that they did little to cause the problem but are often hit first and hardest, from crop losses to rising seas.

According to Corrêa do Lago, even talking about some possible sources of money has been difficult in the official talks, including small taxes on polluting activities or “debt for nature” swaps where part of a country’s debt is canceled in exchange for protecting ecosystems. COP30 did deliver a pledge to sharply increase money for adaptation projects such as flood defenses and drought‑resistant farming, but many negotiators and experts say the promise still falls short of what vulnerable countries will need in a world that keeps getting hotter.

What this means for future climate summits

The mixed outcome in Belém has left climate diplomacy at a crossroads, with almost every country still backing the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming while arguing over the pace of change. On paper, there is broad recognition that fossil fuels must eventually be phased down, yet in practice governments remain divided over who moves first and who pays.

That is why the COP30 leadership argues that progress now depends, to a large extent, on those who are ready to act forming their own alliances and proving that faster action is possible. Ana Toni, the chief executive of COP30, says the political debate over moving away from fossil fuels is “alive” again, and the real test will be whether the new roadmaps on fossil fuels and deforestation can turn that debate into concrete steps before world leaders meet again.

The main interview has been published in the Financial Times.