In 1940, an eighteen year old and his dog squeezed into a hole beneath a fallen tree in southwest France and stepped into a hidden cave painted with powerful bulls, horses and deer that had not seen human light for around seventeen thousand years.

That accidental discovery of the Lascaux Cave near Montignac-Lascaux became an early warning about how quickly human activity can upset a closed natural system. What happens when thousands of people walk into that kind of sealed space every year.

Today, the original cave is closed to tourists and its painted walls are watched over by microbiologists, climate engineers and a small team of conservators. Most people now meet Lascaux through replicas, museum shows and online tours rather than by walking on its fragile floor.

What the teenagers and their dog found

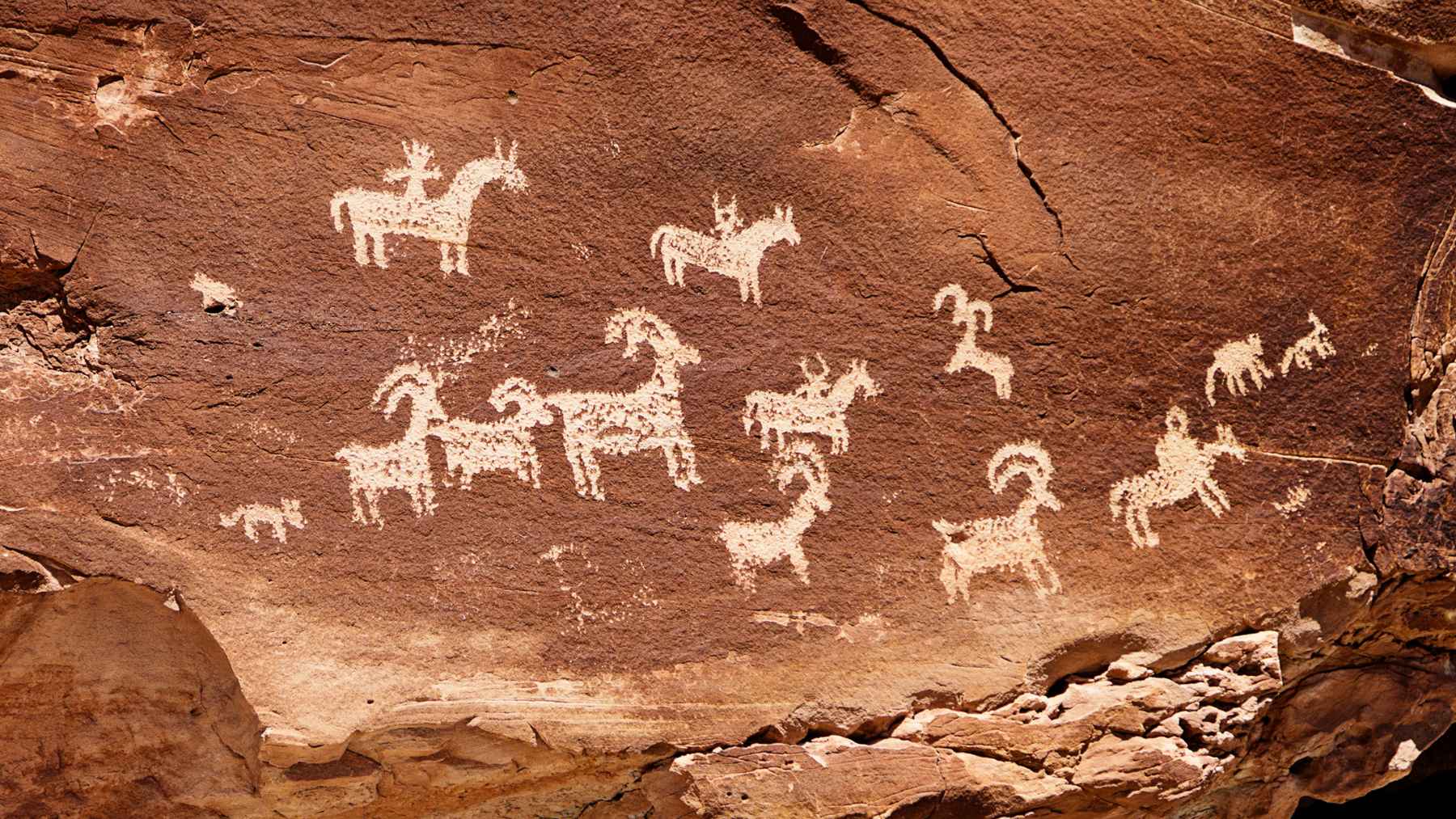

On September 12, 1940, teenager Marcel Ravidat followed his dog Robot into a narrow opening in the hillside above Montignac and came back with three friends to explore it properly. Lantern light revealed an underground gallery where walls and ceilings were crowded with animals; horses, aurochs, bison, ibex, deer and more painted in rich blacks, reds and yellows.

Researchers have since counted more than nineteen hundred engraved and painted figures at Lascaux, including over six hundred animals arranged across nine named galleries such as the Hall of the Bulls, the Nave and the Shaft.

The artists used pigments like ocher, hematite, charcoal and manganese and probably painted from simple wooden scaffolds by firelight high above the cave floor.

When mass tourism meets a sealed cave climate

After the Second World War, authorities widened passages, added lighting and opened the cave to visitors in 1948. Interest exploded and at the peak about twelve hundred people were filing through the chambers every day, each one adding warm breath, moisture and body heat to a space that had been stable for thousands of years.

Anyone who has stood in a crowded subway car on a sticky summer day knows how quickly the air changes. Something similar began to happen in Lascaux.

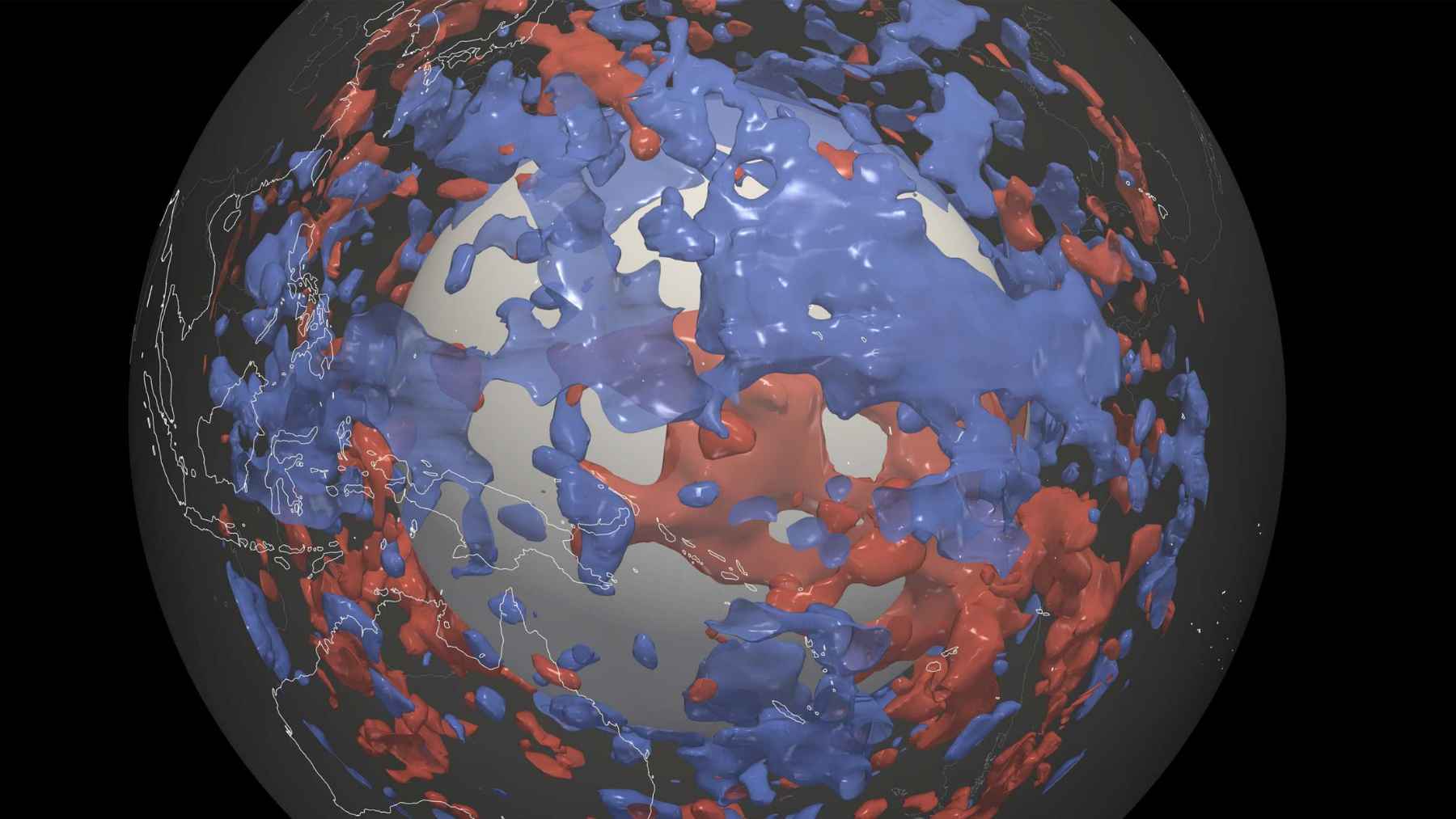

Rising carbon dioxide, tiny droplets of water and shifting air flows helped algae, lichens and crystals spread across the walls. By 1963, green films were visible in key areas and the government shut the cave to the public to spare the paintings.

Conservation work then brought its own surprises. In 2001, technicians overhauled the air conditioning system that was meant to stabilize the cave climate. Disturbance of floor sediments and new airflow patterns coincided with a rapid invasion of the fungus Fusarium solani.

Aggressive treatments with biocides, quicklime and antibiotics slowed that outbreak, but darker fungal stains later appeared and the microbial community inside the cave is still considered fragile.

Digital doubles and lighter footprint access

Faced with the tension between public access and preservation, French authorities began building copies. Lascaux II, a partial replica opened in 1983 near the original cave, recreates key spaces like the Hall of the Bulls using traditional materials and painting techniques, while Lascaux III takes selected panels on the road so museums around the world can show the art without disturbing the real site.

The most ambitious copy is Lascaux IV at the Centre International de l’Art Parietal, which opened in 2016, reproduces almost the entire cave using high-resolution three-dimensional scans and controls light, temperature and sound to echo the original microclimate.

There is also a detailed virtual tour created by the French Ministry of Culture and new virtual reality experiences that let people explore Lascaux with headsets while their shoes stay far from the cave floor. As exhibition designer Dinah Casson has put it, you see this, or you see nothing.

Reading the paintings without touching the rock

Even with this low impact access, the meaning of the art remains an open question. Many panels sit deep inside the cave, in places that would have required torches, prepared pathways and careful planning to reach, which suggests that the act of painting and visiting these chambers was more than casual decoration.

An explainer by art historian Frances Fowle in 2025 highlighted the way images overlap and cluster in remote parts of the cave and suggested that the creative process itself may have carried deep social meaning.

Other scholars point to scenes such as the so-called birdman figure next to a wounded bison as possible mythic narratives while still warning that modern viewers may be projecting their own stories onto Ice Age artists.

At the end of the day, Lascaux is both a time capsule of human imagination and a real-world case study in how quickly a seemingly untouched environment can change once crowds, electric lights and machinery arrive.

For people thinking about mass tourism, cave conservation or even the indoor climate in their local museum, this French hillside offers a clear message. Access always has a cost, and thoughtful design is one way to keep that cost as low as possible.

The official statement was published by the French Ministry of Culture.