A bee that many experts wrote off as gone from New York has quietly buzzed back into the picture.

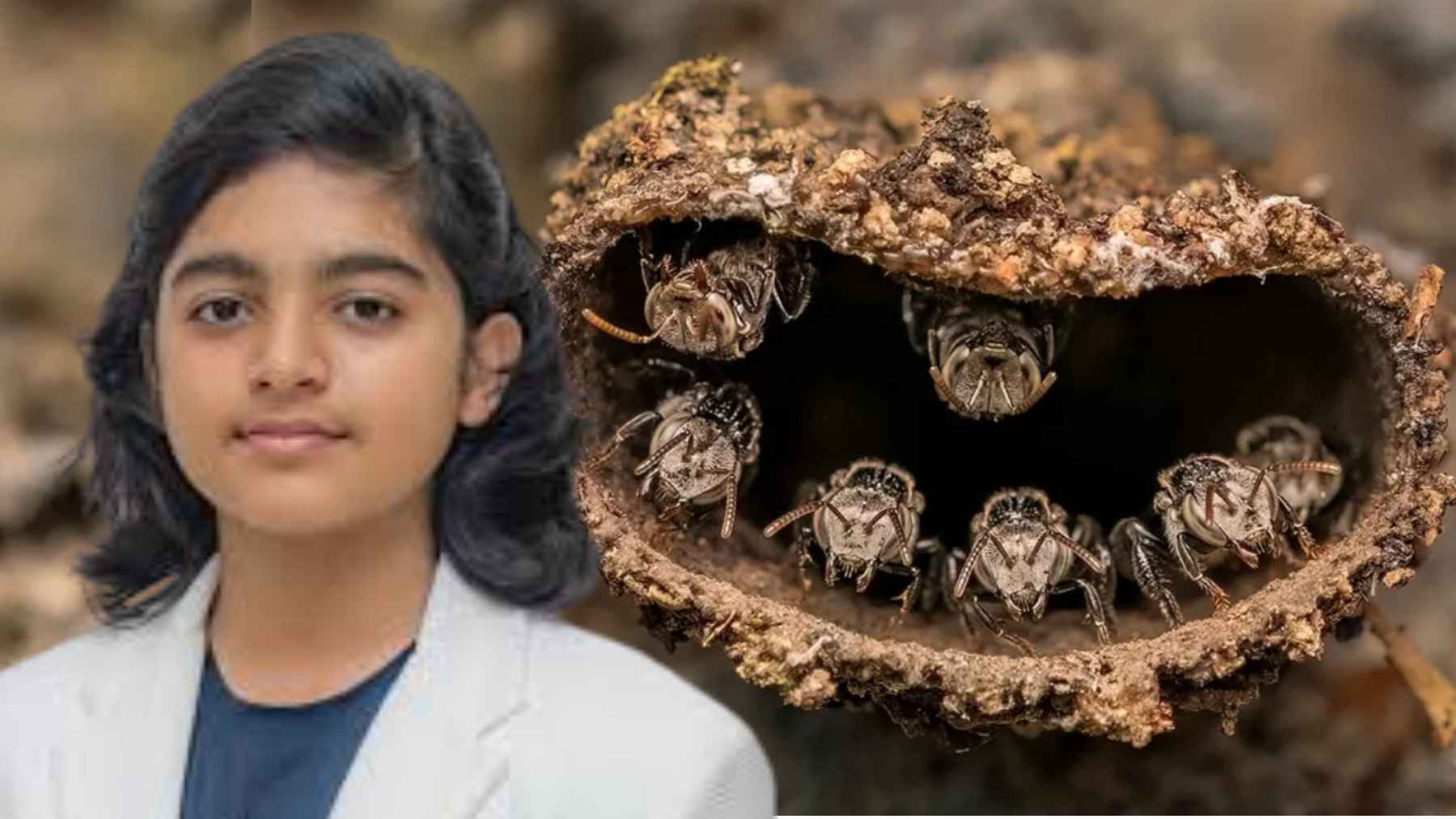

This summer, pollinator ecologist Molly Jacobson spotted the chestnut mining bee, Andrena rehni, in a research orchard at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF) in Syracuse.

She collected two tiny specimens from blooming American chestnut trees, confirming the first sighting of this species in Central New York and only the second known population in the state.

For a long time, the chestnut mining bee was a ghost in the records. It had last been documented in southern New York in 1904. After that, nothing. The New York Natural Heritage Program eventually labeled it “possibly extirpated” in its pollinator survey, essentially treating it as gone from the state.

Now the bee has turned up not only again, but a couple hundred miles farther north than anyone expected. Jacobson calls the Syracuse discovery a “significant record” that expands the known range of the species and suggests it can hang on in managed orchards inside cities, not just in remote forests.

A tiny specialist with one favorite tree

The chestnut mining bee is a solitary, ground-nesting insect. It does not live in hives, and you will not see it crowding around your picnic the way yellowjackets do. Jacobson has even noted that this particular mining bee is not able to sting, which might surprise anyone who hears the word bee and immediately thinks about painful encounters.

What makes Andrena rehni really stand out is its diet. It is a pollen specialist that relies almost entirely on chestnut and chinquapin flowers. Without those blooms, the bee has very little to eat and nowhere to raise its young.

That worked fine when the American chestnut ruled eastern forests. Before a fungal blight arrived in the early 1900s, there were an estimated three to four billion American chestnut trees, roughly a quarter of the hardwoods in the region. The tree was so abundant that people called it the redwood of the East.

Chestnut blight then raced through those forests, killing billions of trees in only a few decades and stripping away food and habitat for wildlife and chestnut dependent insects.

So if the tree nearly vanished, how did the bee survive at all?

From disappearance to rediscovery

For decades, there were no confirmed records of the chestnut mining bee. That changed in 2018, when researchers working in Maryland found it on chinquapin, a shrubby relative of the American chestnut.

In 2023, Jacobson located a population in an orchard at Lasdon Park and Arboretum in Westchester County. A bee specialist at the United States Geological Survey confirmed the identification, and the find was later described in the journal Northeastern Naturalist as the first contemporary state record of Andrena rehni.

The new Syracuse discovery pushes the story further. It is the first time the bee has ever been recorded north of the Hudson Valley in New York. Jacobson has suggested that its presence a few hundred miles beyond its known range hints that other overlooked populations may be hiding in chestnut plantings elsewhere in the state.

Chestnut restoration is not just about trees

The Syracuse orchard where the bee was found is part of ESF’s long running American Chestnut Research and Restoration Project. Researchers there grow a mix of American chestnut, chinquapin, hybrids and Chinese chestnut, testing different strategies to bring back a tree that once shaped entire landscapes.

Some of that work involves conventional breeding. Other efforts explore biotechnological approaches, such as the Darling 58 line developed at ESF, which carries a wheat gene that helps chestnut trees tolerate the blight fungus.

For most city residents, those experiments might seem distant, something happening behind the fence of a research plot. The return of the chestnut mining bee makes the benefits much easier to picture.

As ESF scientist Andrew Newhouse has pointed out, the bee offers a living example of how restoring a keystone tree can ripple out and support specialized wildlife that had nearly disappeared.

What this means for pollinators and people

In New York, the chestnut mining bee is classified as imperiled and is considered one of the rarest bees in the state. Jacobson has described it as an indicator that the surrounding environment is still diverse and connected enough to support species that depend on a single resource and vanish quickly when landscapes are simplified.

There is a practical angle for everyday life too. If a rare specialist can survive in an urban orchard in Syracuse, it suggests that thoughtfully planted trees in cities, suburbs and small towns can host surprising biodiversity.

The same way backyard milkweed patches help monarch butterflies, chestnut groves in parks or on campuses can offer lifelines for insects that almost nobody notices.

For now, the chestnut mining bee will remain largely invisible to the public. It is small, brown and easy to overlook, even when it is right in front of you on a flower spike.

Yet its quiet reappearance tells a hopeful story about ecological repair. When we bring back the right plants, the animals that depend on them sometimes find their way home.

The press release was published on SUNY ESF.