Japan’s new H3 rocket has suffered a second major setback after its eighth flight failed to place the Michibiki 5 navigation satellite into its planned orbit, dealing a blow to the country’s push for a more accurate, homegrown positioning system that underpins everything from precision farming to low-carbon transport.

At first glance, a malfunction hundreds of kilometers above Earth can feel remote from daily life. What does a misbehaving second stage have to do with a delivery van stuck in traffic or a farmer trying to save on fertilizer?

A navigation satellite lost on ascent

On December 22, the H3 F8 rocket lifted off from Tanegashima Space Center carrying MICHIBIKI No. 5, also known as QZS 5, for Japan’s Quasi Zenith Satellite System. According to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, the second stage engine’s planned second ignition “failed to start normally and shut down prematurely,” leaving the satellite short of its target orbit and forcing officials to declare the launch a failure.

JAXA issued a public apology to communities, partners and users who had “high expectations for this project” and immediately set up a special task force led by agency president Hiroshi Yamakawa to investigate the cause.

The failure comes after a rocky start for H3 in 2023, followed by a string of successful missions that appeared to restore confidence in Japan’s new flagship launcher.

Why Michibiki 5 mattered

Michibiki 5 was not just another satellite. It was meant to strengthen QZSS, a regional navigation system that works together with the United States GPS network to provide highly stable and accurate positioning over Japan and the wider Asia-Oceania region.

QZSS currently offers several public services, including standard positioning, sub-meter correction signals and a centimeter-level augmentation service that can deliver accuracy on the order of a few centimeters for specialized receivers.

Applications already range from mobile mapping and fleet management to “IT-aided precise farming,” construction and marine navigation in busy coastal waters.

Japan’s goal is to grow QZSS into a robust constellation with seven satellites in the near term and an eleven satellite system by the late 2030s, providing redundancy if a single spacecraft fails.

Losing Michibiki 5 does not derail that vision, but it does mean another satellite will have to take its place, and schedules may need to stretch.

YouTube: @SpaceEyeTech

A hidden climate tool in orbit

High precision navigation sounds technical. On the ground, it can look as simple as a tractor driving straighter or a delivery truck skipping one extra loop around the block.

Studies of precision agriculture show that guidance and variable-rate technologies can cut fossil fuel use by around six percent and reduce herbicide and pesticide use by close to ten percent while maintaining or even increasing yields.

By applying fertilizer, water and chemicals only where needed, these tools help farmers lower costs and shrink runoff that can pollute rivers and coastal ecosystems.

Japan’s own QZSS materials highlight trials where high-precision signals guide autonomous drones that inspect wind turbines, maintain riverbanks or carry out detailed checks of critical infrastructure.

In transport, accurate satellite positioning is central to smarter routing, connected fleets and, eventually, more automated vehicles. Analyses of GNSS based systems find that real-time traffic-aware routing and optimized logistics can reduce travel time and fuel use, cutting greenhouse gas emissions along the way.

QZSS also carries a dedicated disaster and crisis management message service used for information on floods and earthquakes, a role that becomes more important as extreme weather linked to climate change affects Asia more often.

In other words, satellites like Michibiki 5 are part of the quiet infrastructure of a lower-carbon, more resilient economy. When one is lost, the impact is not just technical. It can ripple through farming equipment upgrades, smart city projects and disaster preparedness plans that depend on reliable signals from space.

The promise and pressure on H3

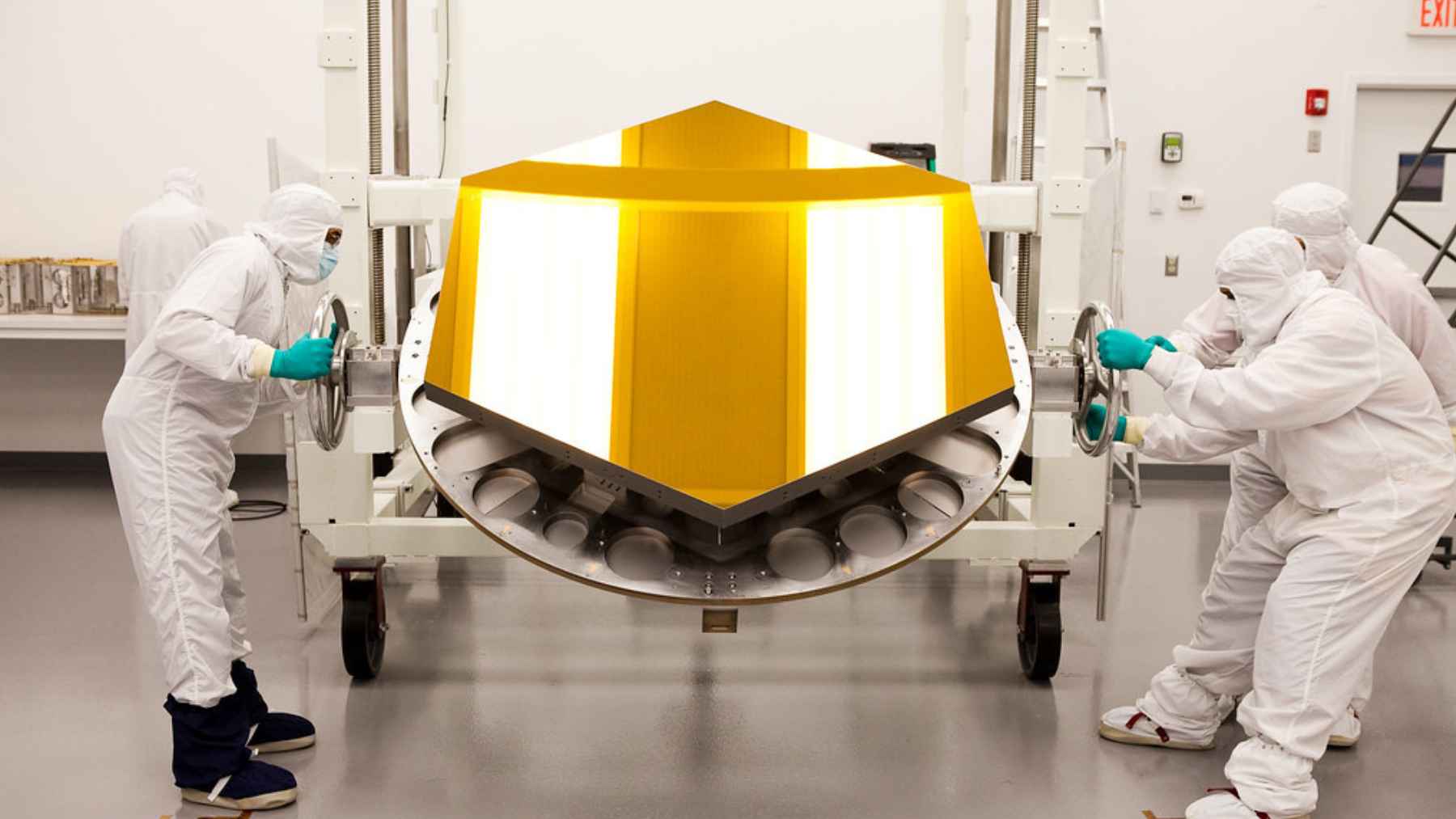

Behind all of this stands the H3 launch vehicle itself. JAXA describes H3 as Japan’s new “easy-to-use” mainstay rocket, designed for high flexibility, high reliability and better cost performance than the long serving H II A.

The system can fly with two or three LE 9 engines on its first stage and with zero, two or four solid rocket boosters, allowing configurations tailored to different payload sizes and orbits.

The standard H3 24L version stands about 63 meters tall and weighs roughly 574 tons without payloads.

Its main engine uses an expander bleed cycle and extensive 3D-printed components to simplify the design, cut parts count and lower both cost and the risk of combustion instabilities.

In practical terms, that means Japan hopes H3 will be cheap and dependable enough to launch climate, navigation and science missions on a regular basis, without every flight feeling like a once-in-a-decade event.

What happens next for Japan’s green data from space

H3’s debut failure in 2023 led to a detailed review and design changes before flights resumed. That earlier episode kept the new rocket grounded for months.

Reuters notes that launch failures in Japan typically trigger long investigations that can delay broader space plans, and officials themselves have called the latest anomaly “extremely regrettable.”

Public schedules still list future H3 missions, including another QZSS satellite and important Earth observation and exploration payloads, although those dates may now shift as engineers work through telemetry from F8.

For people on the ground, the technical details of hydrogen tank pressures and ignition sequences are easy to ignore until they show up as a missing bar of signal on a handset or a delay in rolling out smarter farming gear. The trouble is that the energy transition and climate resilience plans rely increasingly on streams of data from orbit that must be steady and predictable.

Japan’s response to the H3 setback will therefore matter far beyond the launch pad. Getting this rocket back to reliable service is not only a question of national pride or industrial competition. It is part of keeping the digital scaffolding of a cleaner, more efficient society in place.

The official press release was published on the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s website.

Image credit: JAXA – Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency